Transition-age youth (ages 14 to 24) with disabilities encounter numerous barriers that can impede successful employment and education outcomes as they move from high school to adulthood. A higher share of youth with disabilities come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, experience challenges with health, struggle academically, and have lower expectations for education and employment compared to their nondisabled peers (Lipscomb et al., 2017). Additionally, they are more likely to be engaged with the juvenile justice system and enroll in federal Social Security disability programs (Lipscomb et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2011; Stapleton & Martin, 2017). Even with these barriers, engagement with vocational rehabilitation (VR) services has been found to improve employment outcomes among transition-age youth with disabilities (Yin et al., 2023).

Despite the availability of supports, many transition-age youth with disabilities and their families face challenges navigating the change from youth to adult service systems. For example, most disability services offered during secondary school, such as individualized education plans and section 504 Plans, are entitlement-based programs offered through schools. During this period, staff coordinate services using a holistic wraparound approach focused on academic and functional supports. Adult disability service systems, in contrast, are more fragmented, decentralized, and generally subject to additional documentation of eligibility that requires youth to reapply for services, and potentially entail traveling to numerous providers for necessary supports (Moran, 2012). These additional hurdles likely contribute to poorer outcomes related to employment, earnings, and overall postsecondary school enrollment compared to their peers without disabilities (Newman et al., 2011; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.).

Work experiences provide opportunities for youth with disabilities to promote better vocational outcomes. Paid work experiences during high school effectively increase adult employment (Carter et al., 2012), and initiatives for youth with disabilities that focus on education, training, and work-based learning experiences (WBLEs) have positive outcome associations (Fraker et al., 2014; Mazzotti et al., 2021). Even an unsuccessful or short-term job can provide valuable learning experiences for youth with disabilities (Cadigan et al., 2006; Gerhardt, 2006). Work-based programs for youth with disabilities also increase the likelihood of acquiring higher quality employment outcomes, such as jobs that include fringe benefits (Shandra & Hogan, 2008).

Recognizing the potential benefits of WBLEs, the Rehabilitation Services Administration funded five demonstration projects that connected youth with disabilities to early work experiences. HireAbility Vermont, the state’s general VR agency, designed its program to build on its usual services for high school students. Linking Learning to Careers (LLC) emphasized unpaid and paid WBLEs in integrated environments, college exploration, and coursework opportunities at the Community College of Vermont, along with team-based guidance and support from VR staff, dedicated support for assistive technology, and additional transportation funding.

Students developed LLC plans with staff to document aspirations, values, skills, and interests as well as identify short- and long-term employment goals. The LLC plan informed LLC staff as they supported students in exploring work options, training for work skills, and arranging WBLEs (Wissel et al., 2019). LLC staff utilized assessment tools, such as the O*NET Interest Profiler (Employment and Training Administration, n.d.), to match youth’s interests with job openings. They also contacted businesses and employers to develop strong community relationships with potential employers (Martin et al., 2021).

Using a random assignment evaluation design, LLC offered its services to 413 treatment group youth, while 390 control group youth had access to usual transition services. To facilitate WBLE opportunities and service delivery for LLC participants, HireAbility Vermont funded transition counselors, career consultants, and youth employment specialists, some of whom only worked with LLC caseloads, in each of its 12 district offices. In addition to project-specific services, LLC participants could also access the VR services offered to all youth in Vermont. Enrollment began in April of 2017 and service provision continued through summer 2021.

The initial evaluation of LLC included both an implementation study and an impact study. The implementation study found that HireAbility Vermont implemented LLC according to its design, with most LLC participants applying for VR services and opening a VR case, as well as engaging in at least one WBLE during their first 18 months in the program (Martin et al., 2021). The impact study, which followed youth for up to 24 months after enrollment, identified positive changes for two of the three main outcomes of interest. A higher share of treatment group youth had at least two WBLEs and higher rates of enrollment in postsecondary education compared to control group youth. For earnings, however, the LLC program had no impact during the observation window (Sevak et al., 2021).

The current study deepens our understanding of LLC’s implementation and impacts by examining the outcomes of participants over a longer period than did the initial evaluation. The previous impact report presented evidence on LLC’s impacts up to two years after youth enrolled in the program. Most youth had either not graduated high school by that time or had enrolled in postsecondary education. Assessing employment impacts at that point in their transition to young adulthood may have thus been too early. By extending the period up to five years after enrollment, this study allows for the examination of impacts in these areas to answer the following research question: How did VR, postsecondary education, and earnings outcomes differ for LLC treatment and control group members up to five years after enrollment?

Methods

Participants

LLC relied on individual random assignment of recruited participants to facilitate a rigorous experimental design. From April 2017 to December 2018, LLC staff recruited 803 high school students, most of whom used HireAbility Vermont services, to participate in the demonstration on a rolling basis. After parents provided consent, an algorithm randomly assigned 413 students to a treatment group and 390 to a control group. Since random chance determined assignment to the treatment group, any observed differences in outcomes between the treatment and control groups is likely attributable to the LLC program. The implementation evaluation confirmed that the program followed random assignment procedures without any contamination that could bias the interpretation of results. The current analysis omitted three participants (one because of duplication; two because of missing enrollment data), which we do not anticipate creates a risk of bias since the number of dropped cases is small relative to the full sample (What Works Clearinghouse [WWC], 2022). The youth assigned to the treatment and control groups had similar characteristics. At the time of enrollment, youth reported being more frequently in 11th or 12th grade, male, white, and having learning disabilities and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. About half identified as eligible for free or reduced-price lunch and over 30 percent of youth reported working at the time of enrollment (see Table 1). Sevak et al. (2021) provides additional statistics on the characteristics of treatment and control group members at enrollment. Confidence in the experimental design is bolstered by the finding that none of the differences across characteristics between the treatment and control groups are statistically significant (Martin et al., 2021). Significance tests could not be recalculated for this paper as access to these data is no longer available.

Data and Measures

Three administrative data sources provide time series information to support the analysis of VR service use, education, and employment measures.

HireAbility Vermont Administrative Data

We assess whether youth achieved employment goals and maintained a connection with HireAbility Vermont using their case management system. The VR outcomes include achieving an employment outcome, having an open case, hourly wage (of those employed), and weekly hours worked (of those employed). We identified VR outcomes from April 2017 to December 2022. These data include all 800 youth in this study.

Vermont Unemployment Insurance Records

Quarterly earnings from July 2017 through September 2022 come from Vermont’s unemployment insurance system. HireAbility Vermont obtained these data from the Vermont Department of Labor for the 715 youth who provided Social Security numbers to the agency. We estimated impacts using only the subset of 638 youth who provided valid Social Security numbers at the time of random assignment. Excluding those who did not provide a valid number at random assignment, but provided one later, avoids bias in this outcome. If we included those who provided Social Security numbers after enrollment, we would likely introduce bias because treatment group members provided them at a higher rate than control group members (likely because of their LLC involvement). We observed earnings from Quarter 1 after enrollment through Quarter 16 after enrollment and aggregated the quarterly earnings to the annual level to smooth out income variation resulting from frictional or seasonal unemployment.

National Student Clearinghouse Data

HireAbility Vermont’s tabulations of the National Student Clearinghouse data identify enrollment in postsecondary education institutions. The measures of interest include enrollment in any postsecondary education, enrollment in courses at the Community College of Vermont, and enrollment at other postsecondary institutions (the latter two measures are subsets of the first one). We assessed whether youth had ever enrolled in postsecondary education by identifying enrollment at technical training schools, two-year community colleges, and four-year colleges. The National Student Clearinghouse collects student-level enrollment and credential information from 84 percent of all two- and four-year public, private nonprofit, and private for-profit colleges and universities, which includes 97 percent of all students enrolled in Title IV degree-granting institutions (Dundar & Shapiro, 2016). For this paper, analyses used the National Student Clearinghouse data from 800 demonstration participants. Data-sharing restrictions required that HireAbility Vermont provide Mathematica tabulations of these data for treatment and control group members rather than individual records. We identified postsecondary education outcomes from April 2017 through December 2022.

Analysis Approach

Due to differences in data availability, the analysis comprised both comparisons of unadjusted means as well as multivariate regression models. To calculate impacts for the VR outcomes, postsecondary education outcomes, and annual earnings, we compared the unadjusted means of the treatment and control group youth. We could not use multivariate regression models that control for personal characteristics to calculate our estimates because we no longer had the personal identifiers necessary to match the current data with the data initially collected. Because group characteristics were balanced at random assignment, we inferred that LLC participation drove statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups, even without regression adjustments. We used t-tests for continuous variables and z statistics for dichotomous variables to test whether differences between the unadjusted control group mean and the unadjusted treatment group mean were significant, identifying whether this impact was statistically significant at three p-value thresholds: the ten, five, and one percent levels. To investigate earnings effects by timing of enrollment, we estimated multivariate regression models that controlled for the time trend present in the data for early enrollees (those who enrolled before July 2018) and late enrollees (those who enrolled in or after July 2018). For both types of analysis, our significance thresholds were not adjusted for multiple comparisons (WWC, 2022).

We implemented an intent-to-treat framework to estimate LLC’s impact (Sevak et al., 2021). With an intent-to-treat framework, the evaluation assessed impacts across all members of the treatment group regardless of their level of service engagement. This framework did not provide impact estimates of the actual program services youth used (whether any individual service or all of them as a package). Instead, using an intent-to-treat framework provided inference of what impact the program would have if replicated elsewhere in real world settings, with some youth using more services than others. This study design aligns with the WWC Handbook Version 5.0 standards preference for program effects from an intent-to-treat analysis (WWC, 2022).

Results

The results considered were impacts on treatment and control group youth for VR, postsecondary education, and earnings outcomes. The treatment group experienced positive impacts on all but one VR outcome and on two out of three postsecondary education outcomes. Though treatment and control group youth as a whole had similar annual earnings, LLC had positive earnings impacts among treatment group youth who enrolled later.

VR Outcomes

LLC positively impacted three VR outcomes and had no impact on one VR outcome up to five years after enrollment (see Table 2). Improvements across these outcomes align with the LLC program goals of connecting youth with disabilities to HireAbility Vermont services and improving employment outcomes. Compared to the control group, LLC improved the connections between youth and HireAbility Vermont after the demonstration ended. Treatment group youth maintained an open HireAbility Vermont case at a 9.5% higher rate relative to control group youth. This outcome is consistent with the initial assessment findings that more treatment group youth had an open HireAbility Vermont case than the control group (95% and 58%, respectively).

Two of the three employment outcomes contained in HireAbility Vermont’s administrative data improved for treatment group youth. Among youth with a closed case, LLC led to a nearly six percentage point higher rate of employment at case closure. LLC also led to a $2.50 increase in hourly wages among those who closed with an employment outcome. LLC did not impact the number of weekly hours worked among those employed. The initial assessment of LLC did not find a significant impact on any VR outcomes related to employment.

Postsecondary Education Outcomes

LLC maintained positive impacts on postsecondary education outcomes up to five years after enrollment (see Figure 1). This outcome corresponds to the LLC program design, which included enhanced HireAbility Vermont services to positively impact education outcomes. Treatment group youth achieved about a 9% higher rate of enrollment in any postsecondary education and enrollment in courses at the Community College of Vermont. The direction and magnitude of these impacts are consistent with the initial assessment results. Up to 24 months after enrollment, treatment group youth achieved a 9% higher rate of enrollment in any postsecondary education and a 7% higher rate of enrollment in courses at the Community College of Vermont. Neither assessment identified differences in enrollment at other postsecondary educational institutions.

Annual Earnings

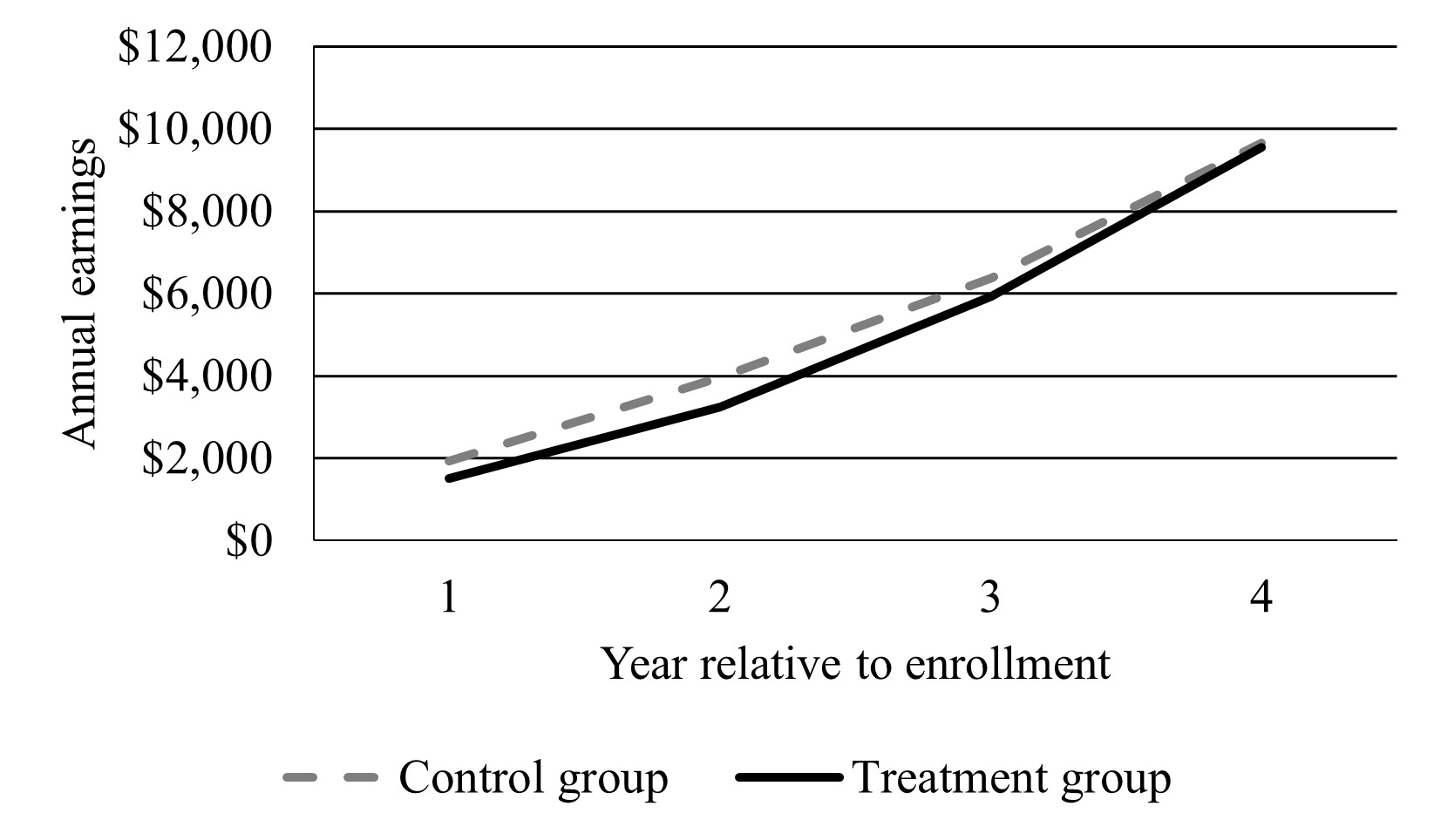

Treatment and control group youth had similar annual earnings up to four years after enrollment (see Figure 2). Regardless of experimental group, annual earnings increased each additional year after enrollment. In LLC’s initial assessment, similar proportions of treatment and control group youth had at least one quarter of earnings within two years of enrollment (66% and 61%, respectively).

Among late enrollees, treatment group youth showed positive earnings effects, whereas early enrollees did not differ based on assignment. When we controlled for the time trend visible in the data, average annual earnings among early enrollees (who enrolled between July 2017 and June 2018) were similar regardless of group assignment (see Figure 3). For late enrollees (those who enrolled between July 2018 and December 2018), treatment group youth had higher average annual earnings compared to control group youth across all years (see Figure 4), statistically significant at the .05 level. No individual year, however, showed a significant difference between treatment and control group youth. These results align with the initial assessment, which found that among later enrollees, a significantly higher share of treatment group youth (66%) had at least one quarter of earnings compared to the control group (55%).

Discussion

This paper explored how VR, postsecondary education, and earnings outcomes differed for LLC treatment and control group members up to five years after they enrolled into an experimental study. Compared to the control group, treatment group youth maintained higher rates of having an open HireAbility Vermont case and enrolling in postsecondary education, doubled the rate of achieving an employment outcome, and reported higher hourly wages. These positive employment findings align with other studies exploring outcomes from work-based learning in a variety of settings among youth with disabilities (Avellone et al., 2023; Cmar & McDonnall, 2022; Frentzel et al., 2021; Patnaik et al., 2022; Schall et al., 2020; Wehman et al., 2020; Whittenburg et al., 2020).

LLC’s components align with contemporary research for WBLE implementation. The LLC intervention included WBLEs in integrated environments, college exploration, and coursework opportunities at the Community College of Vermont, along with team-based support from VR staff, assistive technology, and transportation funding. LLC staff also developed plans for participants, implemented a teaming approach, and developed community relationships with potential employers to connect individuals to WBLE. The design of LLC addresses barriers to implementing WBLEs for students with disabilities identified by other studies (Bromley et al., 2022; Hoff et al., 2021; Rooney-Kron & Dymond, 2021).

Program administrators and staff offering transition services to youth with disabilities could consider similar types of services and strategies to improve outcomes and develop better evaluation strategies to understand the effects of their programs. They might also consider how, in response to its positive experiences with LLC, HireAbility Vermont changed its agency’s practices in substantive ways. The agency extended the age range for transition counselors so youth could experience consistency with their staff as they moved from high school to adulthood, and it also transitioned toward a progressive education model, which emphasized connecting clients to training and education experiences.

An important takeaway from this study is that up to five years after enrollment, treatment group youth continued building their human capital compared to control group youth. For example, treatment group youth maintained higher connection rates to HireAbility Vermont, with one in four still having an open VR case at the time we obtained our data extract. VR staff in other states may find their clients are similarly interested in continued engagement if given the opportunity.

Using multiple sources of data to examine earnings deepens the interpretation for LLC’s impacts. LLC program data showed more treatment group youth closing from VR services with employment. However, when using other administrative data that contained better information on employment, youth had similar annual earnings regardless of group assignment. Differences in results across the two data sources likely reflect youth withdrawing from VR services early, in part because they might be working, and being categorized as unsuccessful closures for various reasons. The program data is useful for assessing program effects, but must be contextualized as having limited information, particularly for those who drop out early.

Differences in average annual earnings between early and late enrollees could be due to program changes during implementation. Treatment group youth who enrolled later experienced higher average annual earnings compared to control group youth, whereas early enrollees’ average annual earnings did not differ across groups. These effects might be evidence of treatment group youth who enrolled later benefitting from greater staff experience with LLC or the program implementation improving over time. Additionally, a substantially higher share of early enrollees had engagement with HireAbility Vermont before LLC enrollment.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic could have affected the LLC program’s impact on employment, particularly in sectors in which youth might be more likely to find jobs, we have no evidence that it did so in ways that differed across the experimental groups. Both treatment and control group members had lower rates of documented earnings in the second quarter of 2020, but those rates rebounded the following quarter (Sevak et al., 2021).

Limitations

Though the five-year findings from LLC are promising, they should be considered in light of their limitations. Since we no longer had access to individual-level data, a statistical limitation is that our analyses could not control for individual characteristics. Fortunately, as noted in the Methods section, treatment and control groups were balanced at baseline, so the risk of bias in the outcomes remains low (WWC, 2022). Additionally, the generalizability of outcomes might be tempered by differences in characteristics between LLC and other program participants. The LLC program had a high proportion identified as male, white, and working at enrollment, relative to the population. Given these differences in characteristics with a broader group of students with disabilities, the program effects might differ for other groups of individuals. Finally, some characteristics of LLC youth (such as employment expectations and experiences) may have influenced the positive impacts on employment and postsecondary education outcomes. The initial evaluation of LLC found that expectations for LLC youth and parents at enrollment were higher than other studies researching the expectations of students participating in special education (Lipscomb et al., 2017; Sevak et al., 2021).

Conclusion

LLC’s design supported high school students in their transitions to employment or postsecondary education through a focus on work-based learning experiences in integrated environments. Up to five years after enrollment, LLC positively impacted the outcomes of youth with disabilities, including achieving employment, maintaining connection with the VR agency, and enrolling in postsecondary education. In response to its positive experiences with LLC, HireAbility Vermont changed agency’s practices to extend the age range for transition counselors so youth could experience consistency with their staff as they moved from high school to adulthood; they also transitioned toward a progressive education model that emphasized connecting clients to training and education experiences. Program administrators and staff working on transition services for youth with disabilities could consider—along with the evaluation considerations raised in this paper— what aspects of LLC they could apply to their work and better serve clients.