Rehabilitation counseling (RC) has been serving American civilians with disabilities since the Smith-Fess Act of 1920 established federal programs to serve this population. The field moved toward professionalization when the 1954 Amendments to the Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) Act delineated the title, functions, and preparation of rehabilitation counselors (RCs), allocating federal funds for the establishment of graduate-level training programs (Chan et al., 2017). Since that time, RC has been struggling to gain recognition and valuation because of historical issues and conflicts (Chan et al., 2017; Leahy et al., 2011). These concerns influence public impressions of RC, training programs recruitment, membership in professional RC organizations, and the legislation and funding of services (Huber et al., 2019).

The current landscape of the RC profession and the social-political milieu surrounding it present a continuing cascade of challenges. The reauthorization of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA) and changes to eligibility by the Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC) have altered the credentialing and knowledge requirements of qualified rehabilitation providers, with lower educational standards weakening the skill set of those serving people with disabilities (PWDs; McClanahan & Sligar, 2015). While early identity confusion stemmed from the debate between RC as a specialty within counseling or a distinct profession (Fleming et al., 2011), this argument has been essentially quelled for the profession by the merger of the accrediting bodies of the Council on Rehabilitation Education (CORE) into the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). This resulted in two incarnations of RC—“traditional” RC and clinical RC, the latter with added emphasis on mental health populations and interventions.

Serving those with behavioral health conditions is not new to RCs, having been a federally mandated population since the Barden-LaFollette Act of 1943; however, specified emphasis on this population presents a potential to overshadow historical VR knowledge and functions in favor of the contemporary mental health services paradigm. This presents a continued, albeit newly iterated, identity crisis for RC: traditional RC vs. clinical RC, or a merger of the two. However, Chan and colleagues (2017) articulated appreciation for both: “Counseling the most at-risk and people living in vulnerable communities within a healthcare and economic climate characterized by outcomes, cost-control and efficiency demands a pedagogically cohesive curriculum that integrates the knowledge and skills of both rehabilitation and mental health” (p. 25).

Despite its strong history and foundation, RC continues to be daunted by the “best kept secret” phenomenon (Patterson, 2009), requiring redoubled marketing and advocacy. Drawing from the movement to bring psychology to the forefront, Patterson articulated a vision for RC that should still be pursued today, stating: “the profession of rehabilitation counseling and the diverse roles of rehabilitation counselors are recognized and valued by rehabilitation counselors, the general public, and other professionals in promoting social justice and equal opportunity for individuals with disabilities” (p. 129).

Rallying cries within the current RC literature call for strategic positioning of the profession, a commitment to innovative research, and new exemplars of leadership to sustain viability in service systems (Lewis, 2017; Zanskas, 2017). Lewis (2017) asserted transformational leadership be embraced, as “empowering everyone to be a leader is consistent with the concept of empowerment in RC as it relates to assisting individuals with disabilities to become self-determining” (p. 13). Zanskas (2017) focused on the need for RCs to be stewards of the profession—those entrusted with the care of a discipline by those within and beyond the discipline. He believed this could be achieved through (a) the generation of new knowledge; (b) conservation of foundational history to drive a vision for the future; (c) transformation of the perception of RC through the effective communication of knowledge, skills, and strengths; and (d) leadership based on the approach of servant leaders. Servant leadership and stewardship are premised upon leading from within the profession. Rather than relying on the structure of professional organizations and elections to lead the charge, it allows leaders to emerge organically and serve according to their means (Zanskas, 2017).

This study was a step toward harnessing the power and potential within the RC profession, to design its next evolution. RC has a strong tradition of research to define the profession through role and function studies (e.g., Leahy et al., 2019) and surveying the perspectives of stakeholders, such as doctoral students and recent graduates (Fleming et al., 2011), leaders of professional organizations (McCarthy, 2020), professionals in the field (Barros-Bailey et al., 2009), and professional organization members (Huber et al., 2019). Although research has been emphasized in this area, less attention has been given to exploring the narratives of collective RC leaders. Qualitative techniques allow for the organic capture of ideas and language, without the constraints of survey questionnaires. Answering the call for stewardship of the profession, this inquiry turned to leaders of the field to anticipate its needs, lend their voice to the vision, and move proactively toward the future.

Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative inquiry (AI) was used as a guiding framework. As it is easy to remain mired in past missteps, arguments, and unrealized potential, AI involves searching for the best in communities to discover ‘what gives life’ to them (Copperrider & Whitney, 2005). The stages of appreciative inquiry are Discover, Dream, Design, and Destiny. Discovering looks at the strengths and peak experiences exemplifying optimal functioning; this is a natural approach for RC, given the long-held value of embracing assets over deficits (B. A. Wright, 1983). The Dream Stage focuses on the possibility of what could be, rather than limiting a vision to what is and has been. Designing is a time for creating a vision of possibility and identifying actionable ideas to move closer to a new potential (Froman, 2010), which flows to the Destiny Stage where members commit to the vision they want to achieve. While AI is traditionally a collaborative group technique, these stages and principles were used to guide the design of inquiry and analysis of responses.

When George Wright (1980) published Total Rehabilitation, the book provided a history of the RC profession up to that point. This inquiry sought to further that work—to understand the profession since that time. The purpose of this study was twofold: (a) to capture the positive history of the RC profession through the voices of its leaders, and (b) to channel the strengths of the profession into a vision that supports its viability, advancement, and longevity. This will be used to engage in the task of transforming the value of RC—to both educate other counseling specialties and reaffirm our position as the most qualified rehabilitation providers serving all PWDs. The overarching research question for this inquiry was: how do personal accounts of leaders in the field of RC ensure the viability of the RC profession and its vision for the future?

Method

Participants

This study employed a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling technique to select participants (Remler & Van Ryzin, 2011). Purposive sampling allowed for the selection of participants likely to be “information rich” (Gall et al., 2007) with respect to RC, rehabilitation philosophy, and the evolution of the RC field. This study is the first phase of a three-part study investigating leaders at different phases of their profession. For this first phase of the study, which sought the opinions of late-career “legacy” leaders, a list of potential participants was developed by a panel of nine rehabilitation counselor educators (RCEs). Potential participants were to have played a significant role in the development and evolution of RC over the past twenty years. Significant role was determined to mean participants met one or more of the following criteria: (a) held positions of leadership in one or more professional associations (e.g., executive board service in a rehabilitation counseling membership organizations), (b) evidence of a body of scholarly work (e.g., substantial volume of publications in the rehabilitation counseling literature), (c) contributions to accreditation bodies and/or academic program leadership (e.g., positions within the accreditation board), and (d) involvement with certification and licensure processes (e.g., national or state-level advocacy for credentialing). A list of 26 potential participants was developed through this process, and an introductory email was sent to each, inviting them to participate. Of those contacted, 18 (69.2%) agreed to participate.

Demographics

Eleven of the participants were male, and seven were female. The majority (n = 15, 83.3%) of participants were Caucasian. All of the participants held a doctoral degree, with rehabilitation psychology (n = 8, 44.4%) being the predominant area of study; given their length of service in the field, it can be assumed all participants graduated from programs prior to CACREP accreditation for rehabilitation counseling programs. All participants were certified as RCs, and nine (50%) held state licensure of some type (e.g., LPC, LMHC, LRC). Participants had been involved in RC for an average of 38.83 years (range = 18 to 53 years), and in RCE for an average of 32.83 years (range = 16 to 50 years). Table 1 outlines the professional association memberships of the participants. Within one or more of these professional organizations, seven (38.9%) had held the position of president, one (5.6%) had been a vice president, one (5.6%) a secretary, and five (27.8%) had served as board members. Participants had held an average of 8.67 individual leadership positions across their professional service.

Procedures

Prior to any data collection procedures, institutional review board approval was obtained through the lead researcher’s institution. An introductory email was sent to potential participants by the lead researcher outlining the scope and purpose of the project. Those who agreed to participate were divided into three groups, with each member of the research team contacting and interviewing six participants. Participants completed a short, internet-based demographic survey through Qualtrics (2019). The interview guide was emailed to the participants a minimum of 48 hours prior to the interview to allow sufficient time to review the questions and consider their responses. All interviews were conducted using video conferencing, although some were conducted with audio only based on the technology availability of the participant. Although the interview protocol (see Appendix 1) was used to guide the discussion and maintain a focus on AI, the interviews followed a semi-structured format, allowing researchers to ask probing questions for greater depth (Neukrug & Fawcett, 2015). Interviews lasted for an average of 45 minutes (range = 19 to 78 minutes). All interviews were transcribed using Temi, an audio-to-text automatic transcription service (www.temi.com). Transcripts were corrected for accuracy by team members, and then anonymized by removing identifying information (e.g., names of universities, state names) and assigning a record number.

Researcher Role

Prior to the data collection phase, each member of the research team submitted a statement outlining: (a) their personal thoughts related to RC, (b) values relevant to the rehabilitation philosophy, and (c) professional experience that created one’s “RC lens.” The research team met to discuss how these potential biases might influence data analysis. To maintain an authentic view of participant responses (Patton, 2015), the researchers decided any participant agreement to summary statements made by interviewers would not be eligible for coding purposes. Only direct comments and ideas from the participants would be considered. Researcher reflexivity was addressed through multiple rounds of analysis, cross checking of findings with the other members of the research team, and consensus building (Morrow, 2005).

Data Analysis

Interview responses were analyzed using common qualitative data reduction techniques (e.g., open coding, memoing, multiple rounds of investigator triangulation) to extract major themes (Charmaz, 2014; Patton, 2015). The overall data analysis process followed recommendations of Braun & Clarke (2006). This six-step process includes: (1) independent analysis and data review by each member of the team, (2) independent development of initial codes, (3) independent identification of major and supporting themes, (4) generation of a thematic map by each member, (5) final refinement of thematic analysis, and (6) production of the final report. To accomplish the first three steps and help control interpretive validity (Altheide & Johnson, 1994), the research team met five times over a three-month period to review independent analysis and reach consensus definitions on general themes. The researchers then reviewed the transcripts using the general themes and generated their thematic maps. Codes were collapsed and refined until the final codes met with unanimous agreement from all team members. Additional meetings focused on the thematic map and the visual representation of the findings to refine further the major and supporting themes prior to the writing of results. A final step to check the validity of the findings was the use of member checking (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Participants were provided the results of the study for their review and asked to comment on the accuracy of the findings. This member checking, with six out of 18 responding, was confirmatory and no amendments to participant responses were suggested.

Results

Based on the thematic analysis and confirmation through member checking, four major themes emerged from the data analysis process: (a) formative influences, (b) threats, (c) current assets, and (d) future directions. Each of these major themes, with supporting subthemes, is discussed hereafter.

Formative Influences

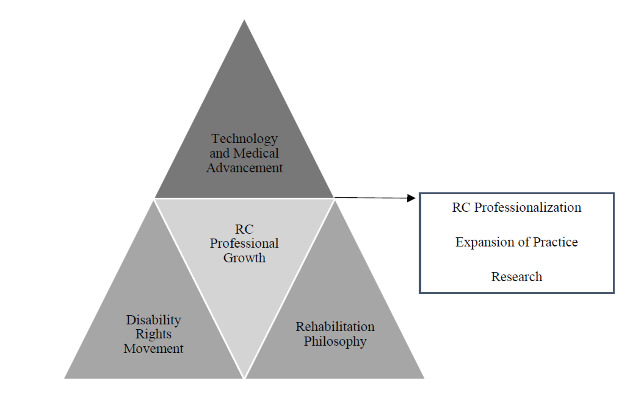

Formative influences were identified as events that influenced the development of RC as a profession. Examples of these events include the Disability Rights Movement (DRM), advancement of medicine and assistive technology (AT), and strengthening of the rehabilitation philosophy. This triad of influences (see Figure 1) helped proliferate the growth of RC. A fourth subtheme, RC professional growth, reflected the professionalization process specific to RC.

Technology and Medical Advancement

Participants identified the growth of AT and medical advancements as playing a major role in the continued expansion of RC. Technology helped increase community access and visibility of PWDs in social settings. Employers have grown to see the value of AT, resulting in increased employment opportunities for PWDs. Overall quality of life of PWDs was impacted through advancements in AT.

Medical advancements led to specialization in and research on specific disability types, helping extend life and opportunities for PWDs. As one participant suggested, “If it weren’t for medical technology, getting us to work with people with disabilities and severe disabilities, I’m not sure where we would have been otherwise.” Another said that the “application of AT…makes a significant difference in the quality of life for PWDs. What was impossible before is now possible.” It was noted that efforts to develop equipment to aid PWDs often ended up being inventions to help all people and society advance.

Disability Activism

The DRM and disability-related legislation were identified as seminal influences on the development of RC, with one participant stating, “Another major force was the Civil Rights Movement… legislation that expanded the civil rights of people with disabilities, particularly the ADA.” While the DRM and disability legislation are interwoven, the specific mention of key disability-related legislation magnified the preeminent impact of these legislative events. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 [P.L.101-335; ADA] and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended [P.L.93-112; the Rehab Act] were two fundamental pieces of legislation repeatedly identified as affecting the RC profession. The influence of the Rehab Act was described by one participant in this way: “Everything we do is based on the Rehab Act. Everything, you know?” In speaking on the values inherent within this Act and their influence on the RC profession, one participant suggested, “The 1973 Rehab Act required that we work collaboratively with people with disabilities…and I think we should preserve those values that we developed so strongly…that there’s a principle in working with people with disabilities.” Participant responses also reflected partnerships of RC professional associations with disability rights consumer groups and other advocacy groups as crucial. This collaborative effort was essential to the passage of legislation and the visibility of disability on a larger social platform.

Rehabilitation Philosophy

When asked to comment on the values inherent to the RC profession, participant statements reflected beliefs and ideas like social justice, person-centered empowerment, multiculturalism, employment, ethics-driven service delivery, strengths-based approaches to consumer interaction, research and evidence-based practices, and changing attitudes and perceptions around disability. These value-driven statements were condensed into the subtheme rehabilitation philosophy. As stated by one participant, central to this philosophy is the belief in “the dignity of human beings and understanding that disability is part and parcel of the human experience.” Evidence-based practices help to inform service delivery, and the passion of RC students and professionals has helped keep disability as a theme in the larger counseling profession. Another participant suggested:

Issues of inclusion and social justice are a kind of fundamental human right…So, I think that you have to really believe in those ideals in order to practice very effectively. And, I think those are really some of the core principles, and with that comes the kind of freedom to fail and dignity of risk and not trying to limit people in their aspirations.

While the expansion of RC and applying strengths-based approaches to service delivery into practice settings were identified, two participants kept the focus on the centrality of work, with one stating, “It’s a belief, first of all, that everybody, pretty much everybody can work.” The other elaborated on the value of employment and expanded it to mental health counseling: “One of the biggest problems for this [psychiatric] population is employment and one of the more potential significant healers of the issues is employment.”

RC Professional Growth

In addition to the three subthemes previously discussed, participant statements reflected the credentialing or licensure process, accreditation growth and expansion, the formation of a code of ethics, training programs, professional organizations and their lobbying efforts, and the 2017 merger with CACREP as key components of the evolution of RC. The pioneering role RC played in certification and accreditation was mentioned: “We were the first of the fields within counseling to actually have an accreditation body…and the same thing about certification.” The following quote reflects this innovative influence further: “We are the first group in the early seventies to develop a certificate program, so that we can advocate for people with disabilities and quality counselors…I think that’s…something we can be very proud of.”

Threats

Though using the positive lens of appreciative inquiry, participants also reflected on threats to the RC profession. These manifested as missed opportunities, shifts in societal mores and behavior, inaction within the profession, and competition from other disciplines. These naturally distributed between internal and external threats to the RC profession, though one intermediary subtheme (influence of mental health counseling) spanned these sides.

Internal Threats

Internal threats included difficulties projecting a unified philosophy/focus and encouraging professionals toward leadership, as well as what one participant summarized as “playing small.” Though practice is driven by values, these were not widely asserted: “The values, I think, are latent, too latent. They need to be reawakened. We need to have some pride. We need to have some fighting spirit.” Early and continuing debate over RC’s role stymied impact, as one participant noted, “I think in terms of professional advocacy, not making up our minds earlier in the game probably hurt us at least in terms of divisiveness among us.”

Educators’ efforts to connect to students were not seen as intentional, and mentoring as not required or systematic, preventing succession planning and the growth of leadership opportunities among new professionals. The decreased emphasis on professional association membership was a contributor to this, as one participant stated, “Students don’t get that kind of initial experience that allows them this idea they could make a difference.” Another response embodied how lack of standardization and common orientation at the doctoral level magnified the issue: “These are our future leaders…how do you train a professional group that practices at the master’s-level with a professoriate that doesn’t even understand the profession?”

Diminished impact was demonstrated through lack of unification among organizations, waning participation with the disability community, an insular stance, and professional complacency. While plurality of organizations offers diversity, the result was reduced power of the profession’s voice and unclear leadership: “there are too many [leaders] and not enough soldiers…there are so many groups…If we are united, we can pass more legislation, have better rights for people with disabilities, and have more allocation of funds.” It was noted that affiliation with disability groups has weakened over time, with the profession focusing on its own growth to the detriment of these partnerships at the national level. These alliances kept practice rooted to the philosophy and mission of rehabilitation counseling, as one participant shared, “We [educators] could have been more engaged with organizations…because, in that space…we direct more effect and we’ll be more authentic with our engagement with the disability community in our own profession.”

Emboldened from early growth, the profession remained siloed and did not strive for timely advancement. The following quote captured this sentiment:

Before, we were initiating, we were innovating, we were entrepreneurial, we had great ideas, we looked at problems, we worked to solve problems creatively….it started to turn, and we’ve just been reactive, because we wanted to just pretend insurance panels, the licensure movement was going to go away. We wanted to pretend we could control the entire profession of counseling or set up our own little island by itself.

Opportunities to assert a specialized skill set, assimilate into healthcare settings, and be included in the counseling licensure movement were missed, as RC focused inward rather than adapting. Continued indecisiveness further impeded inclusion, as one participant noted, “I don’t know that we’ve ever necessarily agreed…whether we keep to ourselves in our own free-standing profession or we move into a broader platform, we never really put our flag in the ground.” Contentment prevented allying with others in general counseling, as another participant surmised, “We just don’t step up and confidently go forward in the work and advocate for who we are…you have to have people who can sit at the table and conceptualize things and be willing to roll instead of resist.”

Intermediary Threats

A single subtheme appeared to straddle concerns within and outside the profession: a shift in RC focus over time. Several participants indicated a narrowed focus toward mental health, while others felt RC philosophy was compromised to fit more readily with general counseling, with one participant expressing, “That’s my worry, that they become general counselors who have a little bit of information about disability.” Similarly, another participant noted a sacrifice of uniqueness by diminishing content areas not emphasized by CACREP, making RC “hardly distinguishable from mental health counseling…some of these unique features I think have really made our specialty special.” By not effectively resolving identity conflict, the culture of the counseling profession was defined by others, leaving RC to be retrofit into that mold: “by not knowing who we are and where we fit, somebody stuck us into a place…it’s not what we bargained for, but it isn’t just a hassle. It really changes the way we look at our business and our consumers.”

External Threats

The greatest proportion of perceived threats existed external to the profession. CACREP was viewed as limiting and changing the nature of RCE, increasing program credits at the expense of mounting student tuition burden, deemphasizing critical knowledge areas, and requiring greater core faculty representation. One participant linked lower passing rates on the CRC knowledge exam to the “watered down” curriculum under current standards. Recruitment and education were further constrained by overreliance on RSA funding to support students. These have further implications for program viability, as echoed in this quote:

CACREP requires you to have X number of faculty and you go talk to the Dean and say, I need two more new faculty; they laugh and tell you to shut down the program because they are not going to risk money, invest money, in a program not making money…add courses, but it has to be small classes…by definition, when you have small classes, it will be a money loser.

Government interest in PWDs and oversight of services vastly changed. Those in administration were viewed as lacking disability experience, managing a budget having “greater emphasis, not so much on the people, but on the money.” This resulted in reduced allocations for ADA compliance, less research directed toward VR services, and weakened requirements for qualified providers. Fiscally driven performance transformed state VR to a business model, where counselors spend more time on paperwork than engaging with clients.

Lack of professional status resulted in other disciplines encroaching into RC knowledge and skill sets. The profession missed opportunities for critical work because of licensure and reimbursement restrictions, as one participant stated, “There will be threats from social work saying they can do our job and occupational therapists and psychologists.” Competition also affected program recruitment, constraining perceptions of workplace opportunities. General misperceptions of the quality, and even existence, of RC further weakened professional standing. On one hand, changing requirements for qualified providers opened the door for “non-credentialed people being seen as rehab counselors and giving a bad name to rehab counselors”; alternatively, having not asserted the specialty widely, RC continues to be confused with other disciplines, while close alignment with the state-federal VR concealed broader utility. One participant noted, “The irony is that most people, if you say, I work for the State VR agency…the public wouldn’t know what you’re talking about.”

At a universal level, an overarching subtheme reflected decreased empathy and less favorable behavior toward one another within humankind, and especially PWDs. Digital culture was a primary contributor to this: “People just don’t exercise enough empathy and compassion…social media has done that, taken the empathy out of everything really.” A secondary consequence of less empathy was increased marginalization of minority groups. Cyberbullying, insensitive language, and unfiltered speech contributed to dividing people. As one participant reflected, “The misunderstandings the public have of people with disabilities and statements on Facebook, and statements on the news and yes, I think the conditions are worse for people with disabilities than they were.”

Current Assets

The current assets, or strengths, of the RC profession encompassed a range that was grouped into four main factors: (a) personal factors, (b) anchoring core, (c) range of work settings, and (d) peripheral factors.

Personal Factors

The rehabilitation field is driven by the professionals, with their variety of backgrounds and experiences, drawn to this work to make a positive impact in the lives of people with disabilities. One respondent described the personal factors this way:

Well, I think it’s a people kind of field. And so, the people that populate our profession are certainly the biggest asset. And I can say that I have known so many really good people, good hearted, competent, dedicated, who really are what makes the difference in terms of the profession being effective in accomplishing its goals.

RCs also were noted to bring passion and vitality to their work, as well as flexibility and creative problem-solving skills to handle a range of challenges. They share similar uplifting values and beliefs, as one described when RCs encounter each other in a professional setting, “Right away you know each other…something about that other person and you immediately feel, ah, it’s one of my people.”

Anchoring Core Factors

Participants observed that RCs have a broader understanding of disability, including the impact on individuals, the psychosocial adjustment process, and an awareness of societal factors. Advocacy was highlighted, such as challenging all of society to include PWDs fully and view disability as a “typical human experience.” Psychosocial adjustment interventions were identified as a specialty of the field, as one participant noted, “Other counseling fields do not know how to help people with disabilities, especially traumatic disabilities, readjust to the new reality.” Supporting this adjustment “requires very specific knowledge and we have years of research experience to use to inform our practice.” The focus on employment and belief in the grounding and therapeutic value of work are perhaps what sets our field most apart from similar disciplines. Here is how one respondent described this:

I think it’s been hard for us to make that as valued as it should be and valued for its uniqueness. It should be, you know, everybody I think has benefited by being in work and it’s not that the other counselors or helpers don’t serve a real purpose, but it’s just addressing the symptoms or the current pain, not the longer term trajectory and independence of the individual, like, I think, economic self-sufficiency can contribute to.

RCs also strive to engage with and understand the point of view of employers and the demand side of the equation, balancing their needs with those of the PWDs who are our primary clients. We also listen to and collaborate with consumer groups, striving to expand community awareness and employment opportunities.

Range of Work Settings

Another asset described by participants was that RCs have the ability to work in a wide range of settings. The field was initially centered on the role of the RCs to work with adults in the public VR system, but developed over decades to include many more roles and settings. Services expanded to include clients across the lifespan in a range of settings from the community to institutions, including the public and private sectors. Participants noted the field also spans policy and consultation work in private legal and Social Security cases, as well as ADA-related compliance and reasonable accommodations issues. One participant summarized this theme: “there’s so many different places and I’ve always looked at this profession as one where there’s a niche for so many different types of people with different interests, different needs.” This variety of roles and employment settings likely gives the RC field a wider range of influence than other counseling specialty areas.

Peripheral Factors

A number of factors were identified outside of the field of RC and its control that positively influenced the profession. The ongoing, but slow improvement in societal attitudes toward PWDs is one of these factors. Decreasing stigma and discrimination and increasing awareness of disability issues were noted as improving access and opportunities for PWDs. A second factor is the apparent bipartisan political support for legislation and services for PWDs, including support for rehabilitation research and the state-federal VR system. One participant captured this, stating, “an advantage is that we have a profession whose outcomes are really, either bipartisan or apolitical…nobody thinks it’s a bad idea to help people with disabilities achieve goals that will help them become more self-reliant and independent.” A final outside factor identified, discussed earlier, is medical and technological advancements, including AT.

Future Direction

The future of RC was painted as a collective effort among the field, its students, strategic partners, and disability groups. Positive direction for growth and revitalization, as well as a return to formative roots, was captured by four subthemes: (a) professional strength, (b) counselor preparation, (c) relationships, and (d) research.

Professional Strength

Actions to enhance professional strength represented a three-prong approach. First, rebuilding professional associations was critical because “the more we do that, the more we create that footprint” to advocate with legislators at multiple levels. A healthy professional organization was viewed as a conduit for lobbying, channeling political capital, supporting research, and creating a collegial space. Rebuilding would be accomplished through unifying organizations and addressing declining membership. Rather than individual associations, especially ones catering to educators over counselors, a singular organization would harness communal knowledge and power, creating a stronger bridge to other disciplines, like behavioral health, allied health, and the medical field.

Humility and having a broader goal were seen as strategies for unification, focusing on profession over organization, and advocating for issues like accreditation standards, provider qualifications, and access to job markets and funding. Common perspective and overcoming “turfism” were suggested to combat professional complacency:

Without action is where we get worn out, [it’s] where we are in a lot of ways, it’s that we’ve just sort of lost that how to move into compassionate action in what we’re doing as a profession, putting ourselves forward.

Second, tapping students and young professionals was the primary strategy for increasing membership. With recent generations more open to connecting, they could “galvanize” a unification movement. This necessitates mentoring to assume leadership positions and providing role models of intrinsic professional passion. This mindset and practice need to begin at the educational level, with educators tuned into and engaged with the profession: “That leads to people thinking, that’s how I want to conduct my professional life. I not only want to be a great counselor, but a leader in the field or the state and maybe eventually at the national level.”

Finally, stronger representation in the broader counseling community would strengthen RC. This included venues such as the American Counseling Association (ACA), Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES), and CACREP, as not only members, but also board members and office holders. Asserting expertise was a pivotal strategy, since “what other group of counselors sees the world that way and is also prepared with specific information?” Having voice would affirm RC values, centering counseling on a strengths-based model.

Counselor Preparation

Subthemes in this area included attracting quality students and providing education responsive to the field. Participants linked student recruitment closely to funding, especially making education more affordable, while not being overly reliant on RSA grants. Students were often seen as drawn to grant funding, rather than passion for the field, with one stating, “If students have no intention to work for people with disabilities, then I don’t think it’s ethical to train people who don’t want to be rehab counselors.”

Despite seeking new venues for practice, participants felt strongly about maintaining an employment focus, though not solely in the state-federal VR setting. Training should focus on preparing students for “the timeliness of services that business demands and the rigor of service quality,” like traditional services of case management and job placement, but also consultative roles such as job analysis, website accessibility, and testing accommodations. Even with the dominance of mental health settings, work was seen as a spanning construct, given its therapeutic value and health benefit for PWDs: “VR is not an outcome. It is an intervention and nothing is more adaptive to one’s mental health than having a job and nothing contributes more to mental health problems and homelessness than not having a job.”

Participants felt curriculum should centrally focus on the traditional content of employment, disability, positive psychology foundations, case management, and psychosocial aspects of disability, insisting CACREP “add to the standards that the role and function studies should dictate” our knowledge base. RCE would be further enhanced with contemporary course content on substance use, practice for a pluralistic society, integration of health and functioning, new technology, and working with individuals in poverty.

Relationships

Relationships outside the RC field were seen as vital to the longevity of the profession. Participants felt service delivery would be better informed by stronger affiliation with the disability community, making it possible “to reflect on practices where we can engage with and for people with disabilities to enhance outcomes in a very meaningful way…we need to form bridges. We need some level of merging.” Combined advocacy toward ADA enforcement, civil rights, equal opportunity, and employment legislation creates better outcomes “for the people we serve. That’s what got us going. That’s why we were created as a profession.”

Connecting with entities outside of RC was seen as an avenue for expanding into new settings and regaining access to broader populations, though anticipating these areas was described as “the real brain trust question.” Bridges were suggested to the corporate sector, geriatric care systems, school systems, substance use clinics, and public health. Reaching burgeoning populations of PWDs would improve relationships with clients, create internships for students, and impact policy. One participant captured this, “We might assume a consulting role. We might do training. We might develop guidelines…we just have to do it on behalf of ourselves in addition to doing it on behalf of clients and not being afraid to go there.” RCs could also actively work to decrease stigma by promoting disability inclusion within general counseling and society, shifting away from pathologizing language and toward educating others. A “social justice agenda” would “normalize everything and help everybody understand disability well enough to have it be destigmatized enough so people could get services in a variety of settings.”

Research

The research subtheme converged on expansion—toward new directions, developments, and theories. Participants called for investigation into emerging topics and populations, like health disparities, aging, poverty, and chronic lifestyle-related health disabilities; applied research for practical issues, like adjustment to disability and workplace accommodations; and new theories for job placement, coping and resilience, and quality of life. The drive was toward evidence-based practice to elevate the stature of rehabilitation research: “We could be the gold standard in counseling…a long-term, multi-pronged, multi-faceted engagement of a number of different areas of people’s lives over time, not a drug.” Research was also seen as a way to raise the profile of and attractiveness to the field, marrying philosophy and empiricism. Accomplishing this would require cross-learning through research and practice consortia and pursuing new avenues for funding, both domestic (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) and international (e.g., World Health Organization).

Discussion

This study was conducted using the framework of appreciative inquiry, which focuses on the positive aspects of a community. Participants identified the bedrock of RC philosophy and values, the professionalization movement, the diversity of knowledge and practice, and a strength-based approach toward disabilities as significant assets to the profession upon which to build a future direction. An unexpected finding, however, was that threats posed to RC represented a natural starting point for a vision for the profession. The influence of internal and external forces to RC can be understood utilizing a structure similar to Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems model.

Traditionally, Bronfenbrenner’s model consists of four environmental levels: (1) the microsystem, where roles and relationships are experienced by the individual; (2) the mesosystem, where multiple settings are experienced by the individual; (3) the exosystem, where the person is not directly involved, but events affect or are affected by the individual; and (4) the macrosystem, representing larger cultural context (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2013). Adopting this paradigm, the microsystem of RC would be represented by counselors, as well as RCEs, and their individual professional behavior. These individuals interact at the mesosystem, represented by the RC profession and relationships among multiple counselors, service settings, and RC organizations. Outside of RC, the macrosystem presents two prevailing forces: (a) external bureaucracy, embodying the general counseling profession and professional oversight (e.g., accrediting bodies); and (b) societal changes, such as recent and current sociopolitical environments. Between these systems, however, is a unique exosystem: the longstanding, diffuse identity conflict RC has maintained. This constraining influence has kept the profession from internally coalescing for strength against external forces. Addressing this identity conflict potentially creates a bidirectional solution for RC—first, resolve historical barriers to cohesion at its internal levels (counselor and RC profession); and, once clarified, use it as the basis to affect change at macro levels. Identity conflict, encompassing the subtheme of intermediary threats, represents a starting point for a response.

Address the Identity Conflict

Through a strong and unified voice, the RC profession accomplished much in its formative years. Despite the profession’s many successes, there has also been splintering and weakening of the profession. The number of professional associations has increased while simultaneously seeing a decrease in membership (Phillips & Leahy, 2012), and debate over RC as a unique profession or counseling specialization still remains, all while outside professions seek to promote themselves as experts on disability. A stronger internal definition of purpose, values, and roles is necessary to bring clarity, for pre-service students through veteran practitioners, if the larger professional community and public are to understand the RC profession. The days of a “best kept secret” must end if RC is to survive and thrive. Unity within the profession is linked to a singular professional identity (Huber et al., 2019). For this reason, addressing the identity conflict can be accomplished through (a) appreciating formative influences, (b) elevating the rehabilitation philosophy, and (c) focusing on assets.

As seen in Figure 1, the RC profession was shaped by its formative influences. A reawakening of these would revive a sense of purpose in professionals. The country is currently engaged in a strong culture of activism, embodied in the #MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter. Similarly, the RC profession should return to its social justice activist roots to advocate for societal change and professional recognition. This should be based on an anti-ableist agenda for education and action, focused on the needs of current and potential clients served (Leahy et al., 2011). RC should adopt a common values statement to assert its professional dispositions, with the work of Beatrice Wright serving as the lodestar for this undertaking (Dunn, 2016).

To elevate the RC philosophy, it must be promoted widely. McMahon (2009) stated, “We must articulate who we are and what we do at every opportunity. Marketing is not a dirty word; it is essential to our future” (p. 122). The philosophy, intrinsic to core roles and functions, is the basis of RCE. Advocacy for greater inclusion of traditional RC content within CACREP standards is necessary to continue these traditions. This also includes asserting current role and function studies be used to drive empirically validated knowledge requirements for the RC specialty standards (Leahy et al., 2019).

Along with the RC philosophy, the assets of the profession should be the impetus for solidifying professional identity. Effective interprofessional collaboration is contingent on counselors’ ability to articulate their own identity and understand the shared and unique assets of other professions (Mellin et al., 2011). Social media campaigns within professional spaces should be developed as new avenues for advocacy and public relations. CRCC should be mobilized as a leader in endorsing the legitimacy of the CRC credential. CACREP should be engaged to represent the value of RC within the general counseling and counselor education community, as “accreditation bodies should foster working alliances and mutual respect for all professional counselor educators” (Chan et al., 2017, p. 25). The value-based, asset-driven perspective of RC should be used as a marketing tool to recruit quality candidates to master’s programs, rather than the allure of RSA grant funding as a driving force.

Strengthen the Profession

Strengthening the profession will require a renewed identity and a coordinated approach within multiple arenas. Professional association leadership is clearly needed to engage in organizational self-preservation activities, such as succession planning, consolidation, and collaboration. Without meaningful, value-oriented engagement from RC leaders focused on a unified vision, it is likely RC organizations will continue to decrease in influence and prestige (Tansey & Garske, 2007). “Organizations naturally adapt, restructure, and reconfigure in order to address new challenges…or they may cease to exist” (Leahy et al., 2011, p. 12). Succession planning is one way to engage practitioners within the state-federal VR system (Tansey & Garske, 2007). Drawing faculty and student leaders from RCE programs, practitioners from myriad practice settings, and members of the disability community will shore up this effort. Deliberate actions are needed through: (a) RC education, (b) leadership and unified direction, and (c) disability allyship/advocacy.

In addition to CACREP curricular requirements, RCE programs should be more intentional in preparing students with skills required for stewardship of the profession, including: skill development, as well as participation, in advocacy (Chan et al., 2017); formal leadership development and mentoring of RC students and early career practitioners (Lewis, 2017); and application of evidence-based and emerging research to serve complex populations (Wehman, 2017). RC educators have a substantial influence on students’ opinions of professional association membership (Phillips & Leahy, 2012) and the “overall interpretation and perpetuation of the professionalization of the discipline” (Leahy et al., 2011, p. 9). Aided by technology, RC educators and students can connect across programs nationally for additional training, discussion, collaboration, and mentoring, to broaden their understanding and awareness of the range of disability issues and potential leadership roles. Leadership development will further be enhanced by creating standards for doctoral training of RC educators to address this area, anchoring them to RC values and philosophy.

The RC profession should reestablish quality participation and allyship with consumer and disability advocacy groups to shape policy, services, and public perception authentically (Chan et al., 2017). RCs should participate in the conferences and organizations for PWDs, and they should be invited into RC discussions (Mitus & Levine, 2021). Greater engagement with the disability community allows the profession to serve as “co-advocates” in creating a more inclusive society (McCarthy, 2020). Given disability variability, cross-disability organizations serving a diversity of consumers, like the American Association for Disabled People (AADP), will create a larger impact (McMahon, 2009). Within professional communities, however, RCs should be on the forefront of teaching and infusing disability within education and practice.

New and continuing leaders can take up the quest for a unified direction for RC. Professional mentoring of emerging leaders and recruitment of BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and disabled leaders (intentional identity-first language) should be deliberately implemented to improve representation and further a disability social justice agenda. Through unification, professional organizations can provide a vehicle for lobbying and collaboration, increasing the visibility of the RC profession and moving it to a proactive, rather than reactionary position (McCarthy, 2020). Unification is only possible if organizations are “willing to confront the forces of organizational self-interest and institutional inertia, and to give up the apparent power and comfort we enjoy within our established but struggling associations” (McCarthy, 2020, p. 185). Associations should engage actively in consortium projects across organizations as a first step to bridging, pooling resources and social capital for efforts like consolidated lobbying for disability legislation and professional issues. Leaders within RC and RCE should also seek positions in general counseling areas/organizations and on CACREP to advocate for RC perspectives (Chan et al., 2017; Zanskas, 2017).

Transcend Barriers

The profession of RC has a history of transcending barriers on behalf of PWDs, though it has become segregated, to an extent, from other counseling professions because services for PWDs were separate (Leahy et al., 2011). Better marketing of the profession has been suggested (Landon et al., 2019; Patterson, 2009), and will improve the perception of RC in the eyes of the public (the macrosystem level). A renewed effort to implement principles of empowerment, self-advocacy, and choice (fundamental tenets of the RC profession) is necessary to shine a light on the value of the profession. Implementing these same principles can elevate RC visibility and status through: (a) relationship building, (b) focusing on employment, and (c) quality research.

Transformation of the RC profession requires “effective communication across boundaries, educating others about our field while recognizing the world-view of other disciplines” (Zanskas, 2017, p. 17). Interprofessional communication and collaboration is necessary to expand the impact of RC services and expertise. These collaborations should be seen as reciprocal and mirror the same demand-side approach RCs take to employment: build relationships and rapport, using the language of the other to gain better access. RCs should advocate for the therapeutic value of work within mental health and substance use systems, as both an intervention and outcome (Chan et al., 2017). Poverty and disability must be linked and addressed more explicitly to tackle systemic, often generational, issues for consumers (Anderson et al., 2017). If other professions see beyond the stereotype of RCs as only “the vocational people,” they will see the added benefit of RC expertise in medical and psychosocial aspects of disability, accommodations, assistive technology, and creating inclusive environments. RCs can infuse discussion of disability into other disciplines to address disparities and inequity, such as health care, human resources, and public health. In so doing, the perceived value of RC inclusion in interdisciplinary environments will increase. Elevating the status of RC can further be accomplished through research and knowledge translation on contemporary disability topics. Rigorous research will lead to publications that affect other fields and lead to relationships with other disciplines to conduct research, write grants, and publish outside RC journals.

Limitations

Participants for the present study were drawn from leaders in the RC field. Evidence of “leadership” was drawn from a balance of empirical contributions, as well as engagement in professional activities. While the research team sought a broadly representative sample, the nature of the qualitative design and small sample size may mean important perspectives were inadvertently missed. As such, cautions around transferability of the findings to all who have contributed to the RC profession over the years remain. Additionally, although the sample drawn for this project sought to balance gender and racial/ethnic perspectives, current implications for multicultural counseling and practices may not be represented fully.

It is also worthwhile to note this data was collected prior to the onset of COVID-19, as well as the social unrest following the death of George Floyd, an African-American man, while in police custody and the subsequent social justice Black Lives Matter protest movement. The impact of these events is not necessarily reflected in the responses of the participants, but as researchers, we acknowledge these events shaped some of our interpretation of the information.

Conclusions

The field of rehabilitation counseling has evolved over time and continues to evolve to meet the contemporary needs of persons with disabilities. Through the appreciative inquiry approach in this study, late-career leaders in RCE shared their views on the design of a strengths-oriented vision for rehabilitation counseling as a field. Given the trends toward state licensure demands, adjustments in accreditation standards for educational settings, and service reimbursement requirements, the findings from the present study can provide guidance to current leadership in certification bodies, educational settings, and state/federal agencies regarding the vitality of the profession.

The findings of the present study also demonstrate a continued need for the commitment to rehabilitation philosophy. Historically, much has been accomplished when rehabilitation counselors and RCEs worked closely with advocacy groups. Other professions (i.e., social work) have taken larger roles in advocacy efforts related to social inclusions movements (e.g., Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ Pride). Given the continuing paradigm of RC as a “best kept secret” resulting from limited to no marketing efforts of the field (Landon et al., 2019), partnering with disability advocacy groups may better establish the prominence of RC as a profession, while also attending to some of the contemporary social movements that impact PWDs. With increasing opportunities to make a difference in the lives of PWDs in healthcare, mental health, and VR settings (Tarvydas et al., 2018), the role of the RC profession has limitless possibilities. With advocacy efforts strengthened through research-informed decisions and evidence-based practices, the RC profession will continue to be a leader and contributor within the counseling profession, as well as disability and employment arenas.