In the 40 years since the publication of Dr. George Wright’s (1980) seminal book, Total Rehabilitation, the discipline of rehabilitation counseling (RC) has changed in many ways, but has also retained its core values and principles. Total Rehabilitation, at the time, was described by a reviewer as, “a near definitive coverage of the subject” and a contribution that, “has added to the field through an exhaustive definition of terms which can be of immeasurable assistance to rehabilitation professionals, scholars, researchers, and students” (Galvin, 1981, p. 131). However, modern service systems, client bases, preferred terminology, societal context, and the professional role of rehabilitation counselors would likely be unrecognizable to Dr. Wright and his contributors.

RC has just passed a major milestone, our 100-year celebration from the establishment of vocational programs for injured veterans (Smith-Sears Veterans Rehabilitation Act of 1918) and the state-federal vocational rehabilitation (VR) program through the Smith-Fess Act of 1920. Lewis (2017) argued that at the 100-year celebration mark, “Rehabilitation counseling must think systematically about its advancement going forward” (p. 12). Several internal and external pressures to the discipline have emerged over recent decades, prompted by major shifts in definition and scope, accreditation, legislation, client demographics, professional organization dynamics, and accountability (see Bishop, 2021; Huber et al., 2018; Leahy & Szymanski, 1995; Lewis, 2017; McCarthy, 2020; Rumrill, Bishop, et al., 2019; Strauser, 2017; Zanskas, 2017). The result has been increased pressure on the profession to maintain relevance, particularly in the rapidly shifting economic and social landscape. The discipline is also seeing greater demands for services due to population increases, aging, and an increasingly culturally diverse populace (Lewis, 2017). The COVID-19 global pandemic has highlighted disparities and vulnerabilities in our economy, political climate, and public health system that disproportionately impact individuals with disabilities and other minoritized communities (Kendall et al., 2020). The pandemic was coupled in time with historical civil unrest due to continued and highly visible racial and economic inequality, resulting in impacts across nearly all areas of life in the United States (Nerlich et al., 2021).

From an education standpoint, the most notable is the change in accreditation bodies from the Council on Rehabilitation Education (CORE) to the Council on Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). On July 15, 2015, individuals on the CORE and CACREP boards concluded that the counseling profession would be more effective with a single set of accreditation standards. The CORE/CACREP merger was finalized on July 1, 2017, with CACREP accepting the role of the primary counseling accreditation body for counselor education programs. As of 2020, CACREP accredited more than 100 RC master’s programs across the country (Peterson, 2020).

Currently, there are two “kinds” of rehabilitation counseling programs accredited by CACREP: Clinical Rehabilitation Counseling and Rehabilitation Counseling. This has been somewhat controversial (Bishop, 2021), but is also subject to the 2023 revision of standards and, based on the current draft (Draft 2 standards, October, 2021), will not be the case going forward. Results of the latest role and function study revealed six knowledge domains considered essential by practicing RC for effective practice: rehabilitation and mental health counseling, employer engagement and job placement, case management, medical and psychosocial impacts of chronic illness and disability, research methodology and evidence-based practice, and group and family counseling (Leahy et al., 2019). These domains, particularly the inclusion of mental health counseling, reflect the shift to CACREP, as well as RCs engagement with the broader counseling field in licensure efforts and the American Counseling Association’s 20/20 vision for counseling as a unified profession with specialty areas (Kaplan et al., 2014).

Recent legislation has impacted the VR setting, specifically the passage of the Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act (WIOA, 2014). This, among other service shifts, elevated transition-aged youth and students with disabilities as a high priority demographic for services. This resulted in a required financial investment in Pre-Employment Transition Services (Pre-ETS) and broadening the customer base of VR agencies to serve students with disabilities who are “potentially eligible,” even before they officially open a case with the agency (Schutz et al., 2021). This shift in resources, with no additional funding, has prompted concern over agency resources and the ability to serve adult customers effectively.

Professional identity and the strength of professional organizations has been a consistent point of discussion over the last few decades. Identity discussions came to a head in the early 2000s, with several efforts to merge with other counseling bodies, and discussions of unification of professional organizations materializing; but ultimately, no lasting change came out of this period (Leahy et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2006). Concerns related to the strength of professional organizations due to reduced membership and stifled momentum have remained relatively constant since the 1990s (Leahy et al., 2011; McCarthy, 2020). The potential consequences of a lack of coherence in the discipline have been evoked for some time. For example, Leahy and colleagues warned a decade ago, “if rehabilitation counseling does not resolve its alignment issues, others outside the discipline will decide for it in one way or another, particularly if we continue to experience significant membership decline and a further loss of resources and political power, which seem highly likely given the trends” (p. 11).

In 2017, the merger of accreditation with counseling (CACREP) was completed, effectively ending the reason for the debate over whether RC is a specialty within counseling or its own profession. While it is doubtful that all constituents agree, many believe it is time to move into a new phase of professional development for RC. For example, Zanskas (2017) urged leaving behind identity arguments post-merger, as under accreditation standards, we are now a specialization of counseling. He argued, “It is time to move forward with a unified voice in order to convince other professionals, state examining boards, behavioral health organizations, and federal agencies who we are, what we can provide, and how we can be of benefit” (p. 17). Others agree that the focus needs to be positioning, such as understanding the need to “think about RC as a profession in terms of its unique attributes and how those provide a strategic opportunity to establish a niche now and in the future that can serve the profession well in terms of longevity and vitality” (Lewis, 2017, p. 14).

The purpose of this study was to explore the views of mid-career rehabilitation counselor educators regarding the history, present, and future of the RC profession. Our goal was to elicit narratives on strengths, assets, and a collective vision for moving the discipline forward in a productive way. The participants were selected based on their years of experience in rehabilitation counseling and counselor education, and their contributions in leadership, research, practice, and policy-building. This study is part of a larger effort where similar interviews were conducted across groups of rehabilitation educators and researchers, including advanced career scholars (‘legacy leaders’; Nerlich et al., 2022), and early career faculty (‘trailblazers’).

The guiding framework for the study was appreciative inquiry. Appreciative inquiry is, “a process that looks into, identifies, and further develops the best of what is in organizations in order to create a better future” (Coghlan et al., 2003, p. 5). Models of appreciative inquiry (i.e., 4-D Model) focus on eliciting information from participants on discovering and appreciating what is, dreaming of what might be, constructing the future, and sustaining change (Coghlan et al., 2003). A common criticism of appreciative inquiry is that it ignores weaknesses or problems, though, given the scope of our study, this was intentional. The approach is purposely constructed and oriented towards areas of vitality and possibility, rather than focusing on deficiencies. The questions addressed by participants included:

-

What has shaped the rehabilitation counseling profession?

-

What core values and ideals are represented at the heart of rehabilitation counseling?

-

What do you view as the current assets in rehabilitation counseling?

-

What should the future of rehabilitation counseling look like, in terms of issues and directions?

Methods

Participants

Snowball sampling was used across the three parts of the study to obtain participants for this study, and for the third and final phase of the study. Snowball sampling methods are common in qualitative research to access participants for interviews (Cohen & Arieli, 2011). Researchers in phase one used purposive sampling to select participants who are considered “legacy leaders” in the field of rehabilitation counseling education. Those legacy leader participants were given the opportunity to nominate up to three individuals for the current study, whom they considered to be an “influencer” in rehabilitation counseling education. Influencer was defined as a rehabilitation educator with tenure, at the associate rank or higher, who had fulfilled leadership roles in the field. Researchers in the current study added 22 potential participants who had been nominated in phase one of the study; however, not all nominated individuals met the inclusion criteria. Researchers also evaluated and added the names of mid-career rehabilitation counseling educators who had served in leadership positions to create a more diverse (gender/racial) sample. Researchers emailed an introductory email to 22 potential participants for the study, describing the research process and expectations for participation. Fourteen (64%) individuals responded with agreement to participate and, following informed consent procedures, completed data collection via participation in a semi-structured interview.

Demographics

Fourteen participants were interviewed for this study with eight (57%) participants identifying as female and six (43%) as male. Nine participants (65%) identified racially as White/Caucasian and five (35%) as Black/African American. Thirteen participants (93%) confirmed their certification as a Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC) with an average time of 27.35 years in the field of rehabilitation counseling (range = 17 to 40 years). Participants had worked as rehabilitation counselor educators for an average of 20.42 years (range = 13 to 26 years). When considering the academic rank of the participants, five (36%) were associate professors and nine (64%) were full professors or equivalent. Table 1 outlines the participants’ membership in RC-associated professional organizations. Within those professional organizations, ten (71%) had held the position of president, eight (57%) reported having been a vice president, and nine (64%) reported they had been a board member-at-large. Participants reported they have been members of an average of seven professional organizations and held an average of 5.84 individual leadership positions across rehabilitation professional organizations.

Procedures

The current study was phase two of a three-part study. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to data collection procedures. Willing participants were interviewed by one of the first three authors. Researchers scheduled a video or phone call based on the participant’s preferences and schedule. Prior to the interview, participants were sent a link to a short internet-based demographic survey on Qualtrics (2019) and the basic interview questions ahead of the scheduled interview to allow time for considering responses. Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format that allowed researchers to ask clarifying follow-up questions when necessary (see Nerlich et al., 2022 for the full interview protocol). Interviews ranged from 37 to 102 minutes in length, with an average length of 54 minutes. Interviews were recorded with permission and transcribed prior to analysis.

Researcher Role

Qualitative data analysis requires additional levels of researcher interpretation; as such, there are unique ethical considerations to be explored (Creswell & Poth, 2018). One way to mediate the impact of researcher bias on the interactional data analysis process is through written researcher self-disclosure about the topic called a reflexivity statement (Creswell & Poth, 2018; De Fina, 2009). Reflexivity is the process of researcher self-examination as it relates to their social origins and personal and professional demographics, as well as their relationship to the research topic (Bourdieu, 2003). This process is vital to the rigor of qualitative research, as it makes transparent the ways in which a researcher might be influenced by their own experiences and narratives (Macqueen & Patterson, 2021). Below is each researcher’s reflexivity statement. These were written by all researchers on the large three-part project prior to data collection and shared within a private drive file. The third and fourth authors on this paper served as auditors only; therefore, their reflexivity statements are not included.

First author is a white, cisgender female, who is an associate professor in a counselor education program. She holds office in a national professional association. Her counseling background is with the VR program, and her research is largely on addressing employment issues, particularly in the transition population and college students with disabilities. Her biases as stated initially included observations that the emphasis on reaching parity with counselors and the push to ensure students pursue licensure has diluted some of the rehabilitation content in education programs. This decision limits some options for the field in terms of growth and ideal vision and makes us subject to competition from external forces (most notably, mental health counseling).

The second author is also a white female who is cisgender and an assistant professor in a rehabilitation counselor education program. Her professional background includes work in two state VR settings, and her research explores employment and quality of life-related issues for people with disabilities. Her biases stated initially included a lack of efficient marketing in the field of rehabilitation counseling leading to a lack of public understanding of the profession and lack of inclusion on important issues to the field (e.g., accreditation, legislation). She also noted that there is a lack of unified perspective in the field, leading to a fragmented profession.

Data Analysis

Participant interviews were digitally recorded, then professionally transcribed by an external agency. Any identifying content within the transcripts was redacted and mentions of other rehabilitation professionals were also removed. Following the return of the transcripts, each was cross-checked by the authors to confirm accuracy. Participant data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s six-step process (2006). The process includes (a) familiarizing oneself with the data, (b) creation of initial codes, (c) combining codes into themes, (d) reviewing themes as they relate to coded data, (e) defining and confirming themes, and finally, (f) selecting quotes that best illustrate the identified themes.

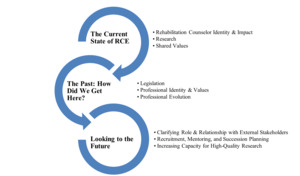

First, two researchers independently read and re-read all participant transcripts. Next, researchers individually noted themes they felt were patterned in the data. Researchers identified quotes and frequency of themes within interviews and met five times over six months to seek consensus on themes and the terminology used to define themes. The two researchers used the defined themes to create individual thematic maps. The thematic map (Figure 1) was used as a visual representation to refine the primary themes and supporting themes before finalizing the results. Finally, researchers identified quotes from the transcripts that best illustrated identified themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Results

Following data analysis, identified themes were presented in a way that best illustrates the participants’ understanding of the state of the profession. The three primary themes found in the data are: (a) The Current State of Rehabilitation Counseling and Education, (b) The Past: How Did We Get Here?, and (c) Looking to the Future. The results begin at the current time, as participants explored the critical period of professional identity they find themselves in. Within each primary theme, subthemes are explained, and participant quotes are included to provide further context to the findings in the data.

The Current State of Rehabilitation Counseling and Education

Participants, in their discussion regarding the present state of the profession, commented on several aspects of the rehabilitation counseling discipline, including discussions of (a) rehabilitation counselor identity and its impact, (b) research, and (c) shared values.

Rehabilitation Counselor Identity and Its Impact

Several respondents described the current RC identity as a weakness, many using variations of the term “crisis.” Some attributed it to collective concern over how people outside of the discipline view “us;” for example, “our confidence about who we are within the context of the larger world is challenged, and I think there are times when the identity that we’re trying to accomplish seems to be more externally driven than internally driven.” Other descriptions of our development reflected the concept of being in flux, thinking of the current state as a part of our developmental trajectory, rather than our final destination. This problem is compounded through our work teaching and mentoring, as we communicate our own view of what a rehabilitation counselor is and does to students and trainees. Several respondents noted their view of the consequences of our lack of alignment on identity. One described the impact as, “partially our identity crisis and not really being able to decide who we are as a profession, because we’re supposed to articulate that to students; and they get so many different mixed messages from professors that they interact with.” Another pointed to the merger as a major source of trouble in this area, citing it causes “worry about professional values and scope of practice being watered down, seeing students identify with mental health rather than RC, [we] need to emphasize identity with students.” Ultimately, most agreed that the topic of identity and alignment is critical, an area where we need to come together. One respondent explained their view this way:

…looking at different changes, as it relates to certification, licensure, accreditation…I think there is definitely a need for us to be sure that we’re all on the same page as a profession. I think one topic that we continue to visit is professional identity.

As for the relevance of RC, participants generally stated that our skills and approach, as guided by our counselor identity, are useful and needed. For example, “I think that in the world of counseling and human services, we are absolutely immersed in all of the hot topics. We may not realize it, but we are, as professionals, in every environment.”

Practice Settings and Scope. Unsurprisingly, as participants varied in their description of RC identity, this translated into divergent views on the settings and roles rehabilitation counselors should fill within the broader counseling field. Some respondents expressed strong belief that an employment focus for persons with disabilities be at our core, and that expansion into broader counseling settings and greater attention to mental health is a betrayal to our history and values. One particular area of concern related to the philosophical approach of rehabilitation counselors compared with other counselors, as we conceptualize individuals from a strength’s perspective rather than pathologizing. Two respondents explained their concerns about expansion, “[Some individuals] think we lost our way because the real beauty of what we do is we connect a person with a disability with a job and that that’s the one thing that as rehab counselors we’ve outsourced and given to paraprofessionals,” and “particularly post-merger, we cannot lose sight of employment, independent living, full community participation.” One respondent expressed disapproval with the curricular changes associated with the merger:

I feel that what we’ve done throughout the curriculum, and our identity, is to sell our souls to a values system that is inconsistent with rehabilitation and the philosophy of rehabilitation, inconsistent with the ICF [International Classification of Functioning], inconsistent with broader disability conceptualization, and to go to a diagnosis-based model that is based on you diagnose people and then we treat, which has not been a rehabilitation philosophy over the course of time.

Others expressed support for this expansion, arguing that rehabilitation counselor training is a good match for addressing mental health needs, and because of our rich history of being interdisciplinary we have the potential to fill a void related to the mental health and adjustment needs of individuals with disabilities. A respondent described how inclusivity is part of RC roots:

We may have a specialization, as we have counseling, but if you think back to the very beginning of rehab counseling, it was interdisciplinary by nature—so you steal a little from medical, steal a little from social work. We have a specialization, but to complement specialization, our whole base is pulled from other disciplines.

Another participant described the consequences felt by being overly focused on employment, and not pursuing a greater role in mental health:

We boxed in our field by not paying attention to the mental health needs of persons with disabilities. We talk about psychological adaptation, but not the psychological impact/trauma that individuals may experience as a result of acquiring their disability, or family members’ experience because someone was born with a disability. This cuts us out of mental health because ‘our area is work’ and now we see the consequences with the CACREP merger/licensure. However, this leaves no one available and capable of addressing mental health needs within the context of disability – lack access to holistic services they should have. Mental health counselors are not trained for this.

A few respondents expressed regret that RC missed some opportunities to connect with consumer groups who are key demographics to our mission and failed to capitalize on opportunities related to other service sectors. Most notably, our failure to fully integrate into the Veterans Administration, expand into Workers’ Compensation, and engage private rehabilitation to the degree that we could was limiting. Ultimately, respondents, in their comments, reflected a divide that has been observed for a long time, that what RCs do (or should do), and in what setting, continues to be open to interpretation. On one side is the notion that employment is central to the RC mission and values, with additional positive outcomes, such as quality of life, financial security, and access to opportunities, dependent on work. On the other is the perception that the skills rehabilitation counselors have are valuable and transferable to many other settings outside of state VR and employment services, where we can support individuals with disabilities towards their desired life goals and outcomes.

Some noted that RCs current status is directly tied to legislation and advocacy work performed not by rehabilitation counselors themselves, but by individuals with disabilities. Examples were provided by respondents related to the National Federation for the Blind and their work to promote access to technology, Autism Speaks and their efforts to increase funding, and the advocacy that went into the passage of the Rehabilitation and Americans with Disabilities Acts.

Accreditation. The CORE/CACREP merger was mentioned nearly ubiquitously in participant interviews. The merger was another specific area of divergence in participant viewpoints. Some respondents viewed accreditation positively, stating that the merger was a constructive development and has improved our current situation. Others lamented the results of this shift, citing concerns over the increased emphasis on mental health counseling to the detriment of the ability to sufficiently address other topics (e.g., supported employment, rehabilitation philosophy, psychosocial adaptation, private rehabilitation) in the curriculum. At the doctoral level, the introduction of accreditation standards where they did not previously exist, prompted some respondents to comment on the impact of this change.

A notable concern was whether our current accreditation standards reflect the historical context and evidence-based approach (i.e., role and function studies) that our previous accreditation did. For example, “We looked at the role and function studies. We had that historical context. And I worry a bit that the accreditation standards and job descriptions and the professional stuff doesn’t reflect that body of work as much anymore.” Other concerns were related to faculty issues, such as whether the new requirements for graduates and the grandparenting process would in fact protect opportunities for those who had not graduated from a CACREP program, but met the experience requirements, and the degree to which faculty searches are impacted by a need to have individuals to teach particular courses. A few respondents noted the efforts in the 2023 standards revision to infuse disability concepts throughout the curriculum for all counselor trainees. This respondent expressed a mixed opinion on the impact of accreditation that was reflective of several participants:

I feel like accreditation and some of the things, through licensure…has done more to stifle the world of counseling than it has to help it. Obviously, there needs to be some standards and some level of quality, but the extent of the requirements and the pressure to fit so much into such a small place in terms of the curriculum location has driven, in my opinion, creativity out the window.

Licensure. Licensure was also discussed in many interviews. Opinions expressed on this topic were divided: some individuals were pleased with the progress, with rehabilitation counselors able to gain licensure; others perceived the move towards licensure as a threat and a missed opportunity, as it moved us away from counselor roles and settings that are more central to our roots (e.g., state VR, private rehabilitation, and Workers’ Compensation). Some individuals also expressed that not being more intentional about involvement in advocacy for inclusion of rehabilitation counselors in licensure was a missed opportunity and that our position was weaker as a result. For example, “The movement in licensure was one that, because we missed it the first time around, we were kind of forced to the table later.” Some respondents talked about specific issues around licensure that are currently evolving, for example, whether the CRC Exam is accepted as the knowledge exam, or whether state licensure laws are friendly to rehabilitation counselors. One respondent lamented how things unfolded:

Counselor licensure has probably been one of the biggest, most powerful things that has shaped the profession and I am not sure that’s for the better…it has stripped away core elements of our identity that make us unique and make us very valuable, and has really made us conform more and more over the last 25 years to be the low-end version of mental health counseling.

Professional Development: Organizations and Leadership. Comments on professional organizations were mixed. Some individuals held them up as a strength, specifically noting the commitment and energy of emerging leaders and newer professionals. Others were more negative in their view of our professional organizations, pointing to the splintering effect of having such a large number with little collaborative activity across groups. One respondent described the strength of the National Council on Rehabilitation Education (NCRE) and how it has grown over time:

I think NCRE, as a whole, has become a much stronger organization. When you look at the size of the organization, the scope of conferences, the level of attendance, I think there’s more people at least in academia more involved in a certain organization, probably more than there has ever been. I think there is certainly room for growth there, and I think among professional organizations in rehabilitation counseling, that’s one I have seen grow over 20 years relative to the decline or at least recession of most of the other bodies that represent rehabilitation counseling. So I do think that’s been a standout way, at least for educators, to come together.

CRCC was also noted in a positive light as a stabilizing force over time, with one participant stating, “[the] CRC, having that is an asset, despite all the changes that have occurred within accreditation, licensure, RSA, etc. That’s been a constant that everyone can look to and identify as far as what a rehabilitation counselor should at least know.”

However, areas of weakness were also observed. Several participants described challenges associated with having so many different organizations and the lack of collaboration. Others pointed out a lack of succession planning, and limited enthusiasm for leadership observed by mid-career scholars. One respondent noted running unopposed for the NCRE executive team. Communications with NCRE staff revealed that in the last 10 years, seven candidates for executive leadership have run unopposed. A respondent shared their concern:

The fact that I ran unopposed honestly concerns me, because I thought why aren’t there more people in my level on the middle level, where I’m at as a professional in this field, why aren’t more people wanting to move there?

Research

Research was noted as both a strength and an area of necessary growth in rehabilitation counseling. Many individuals pointed to a strong body of knowledge and developing work to identify and refine evidence-based practices as current assets. A respondent described their view on our research base as an asset:

I think that we have a large fund of knowledge through research. We have a longstanding history of conducting really quality research through our journals. We have really strong journals, and I think that that’s definitely a huge asset, is our understanding of the people that we serve and the experience of people with a disability based on that research.

Other respondents noted that research is an area we need to improve. An aspect of the issue was posed as a capacity problem, at least in part due to the closing of several programs at research universities in the last 10 years, “I think we have less capacity today than we did 10 years ago, unable to do good, effective research that is informed by theory and that has practical applicability.” However, other issues were also raised, such as the pressures on faculty to balance research responsibilities with teaching, mentoring, and service, as well as training issues during doctoral study:

We’re not doing a good job moving those high-quality students and doing a really good job promoting research and doctoral work to what we think are our most talented individuals that I think we could do a much better job in that regard.

Shared Values

Respondents noted that within the rehabilitation counseling field, our values are largely shared, and for the most part, are consistent with historical values from leaders such as Beatrice Wright. The preamble of the ethical code was held up as a demonstration of values and consistency over time. Social justice, a concept that has become more prominent in recent years, along with respect for diversity and recognition of disability as an aspect of identity, was held up as an example of a long-standing value of RC. Advocacy, empowerment of persons with disabilities, and inclusion were also notable values expressed by several respondents. Among counselors, a few respondents discussed service to others, and perseverance and problem solving as a value. These values are demonstrated by persevering in the work; despite increasing environmental challenges and funding cuts, rehabilitation counselors are “in the trenches” kind of people. A few respondents suggested we are still not truly and completely living our values, particularly in the realm of advocacy, for several reasons. These included fear or self-preservation, lack of attention to individual bias, a values clash between our traditional holistic approach and the new emphasis on mental health associated with CACREP training and licensure, lack of legislative support for the notion that everyone can work (regardless of disability severity), and job demands (e.g., paperwork) that may take away from being more person-centered.

Past: How Did We Get Here

Interview questions focusing on foundational influences, such as “What has shaped the rehabilitation counseling profession?”, revealed data related to the profession’s past and its impact on the current state of the profession. Subthemes within “past” include (a) legislation, (b) professional identity and values, and (c) professional evolution.

Legislation

Rehabilitation counseling, as we know it today, has a rich history beginning in 1920 with President Woodrow Wilson signing the Smith-Fess Act, establishing the first vocational rehabilitation program (The Civilian Rehabilitation Act). Then, in 1935, vocational rehabilitation was made a permanent federally funded program with the Social Security Act (Wright, 1980). Participants described the profession of rehabilitation counseling as one that has been impacted immensely by legislation:

I would say this field is very much driven by legislation, so if you think about the Americans with Disabilities Act, if you think about the Supreme Court decision in Olmstead in 1999, and the emphasis on full community inclusion for individuals with significant disabilities, and then self-determination in the 1990s, WIOA in 2014… the legislation, it definitely shaped rehabilitation counseling as a profession.

Within the Vocational Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1954 (P.L. 565), funding was provided to create and sustain master’s-level rehabilitation counseling training programs. One participant explained how this is a benefit for the profession, “we have the support of the Rehabilitation Services Administration [RSA]. I think that’s a strength of our association. What other organization provides scholarships for people who would like to come into the field? I do feel like that’s incredible.” The existence of training grants through RSA was noted as a strength of the profession and a way many students are recruited into the profession.

RC has been impacted by, as well had an impact on, legislation: “I really feel like legislation, with the changing with the Rehab Act, reauthorization of the Rehab Act, ADA in the 1990s when they started really looking at barriers and work, [it] started changing what rehabilitation counseling was looking like.” As a profession that is embedded within federal government funding and programs, participants made it evident how significant the relationship between rehabilitation counseling and federal legislation has been. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 [P.L.101-335; ADA] and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended [P.L.93-112; the Rehab Act] were two seminal pieces of legislation noted by participants as most impactful on the profession.

Professional Identity and Values

Social Justice. The profession of RC has a foundation based on social justice and the inclusion of persons with disabilities fully in society. Social justice has been defined as the perspective that all people are entitled to equal access to social, political, and economic rights and opportunities (Alston et al., 2006). Individuals with disabilities face multiple disadvantages in accessing each of these areas. Historically, the field has been an advocate of social justice and equity, even before the Civil Rights Movement and Disability Rights Movement brought civil rights to societal consciousness. A study participant noted, “We were practicing social justice before it was coined, before it was fashionable.” For RC, social justice has always been related to advocacy for people with disabilities to be able to participate in all segments of society, with a focus on employment and independence. One participant stated it well, “… the successes of the profession as a whole have really been driven by persons with disabilities advocating for better lives, greater inclusion, greater independence.”

Organizational Strength and Vibrancy. Within the counseling profession, the CRC credentialing system is the oldest mechanism of establishing counselor credentials (Leahy & Holt, 1993). One participant described the CRC credential as “one of the greatest successes of the field.” Professional organizations were noted as both a strength and a weakness of the RC profession. Some participants explained that having too many professional organizations has caused confusion and fragmentation of the profession. One participant stated,

We have fifteen of them. We’ve always had fifteen of them; at one point in time we tried to give them like, broke down in an alliance, then you have the ones that were major that have become minor in ways that are not helpful.

Unfortunately, even with strong professional organizations and a reputable credential, RC has always struggled with a type of identity crisis. One participant succinctly described this: “despite our [field’s] contributions, we’ve always had an inferiority complex.” The internal tension within the RC profession stemmed from disagreements about the professional identity of rehabilitation counselors and where we fit in the larger counseling profession. One participant explained this as, “what is the core identity of a rehabilitation counselor, are they a counselor with expertise in vocational rehabilitation, or are they a vocational rehabilitation provider that knows how to make a human connection through counseling techniques?”

Professional Evolution

CORE/CACREP Merger. One of the perceived benefits of the merger was “having a seat at the table” to have a voice in decisions impacting the larger counseling profession. Those who were pleased with the merger felt as if RC accreditation now being housed in CACREP brought us into the larger counseling field, and “put us on par with all the others [i.e., school counselors, mental health counselors, marriage and family].”

Participants reported mixed feelings about how the merger occurred, as well as the consequences and benefits of it. Some participants described feeling as if rehabilitation counseling should have merged with CACREP in 2006 or in 2011, when there were earlier opportunities to do so. Participants explained that professional organizations also had mixed views of the merger; this was described as:

At that time, the president of NCRE wrote a letter in opposition to the merger. The president of the American Rehab Counseling Association wrote a letter in support of it. And so what happened was you had major organizations within the profession taking opposite views of the importance of licensure of our overall recognition and importance in the overall counseling profession.

Not all participants agreed that the 2017 CORE/CACREP merger was the best thing for the profession. Some described feeling as if the field has “moved away from what RC truly is” or “I have worries about…our own professional values and scope of practice being watered down.”

Research. A common participant response regarding the strength of the RC profession was specific to research. One participant noted that “…among counseling professions, (RC) has always been one of the stronger, more research-oriented areas.” Research-related topics included the use of evidence-based practices (EBP) in rehabilitation counseling, and the use of the role and function studies to have “an empirical basis for [the RC] profession and what we do.” The role and function studies were also noted to be “really impactful in terms of how we educate students.”

Leadership. Leadership was noted by study participants as an important part of the evolution of the rehabilitation counseling profession. One participant described the importance of leadership as, “we have very strong leaders within our professional associations and accreditation bodies, certification bodies, and I think having the consistent leadership that’s definitely served to shape the profession.” Participants indicated that current leaders in the field were influenced by those who led before.

Not all participants felt that leadership was a strength of the profession, several noted gaps in rehabilitation counseling leadership. For example, one participant described feeling as if “there’s a huge gulf” in RC leadership with strong leaders among the most senior members of the profession, and leadership within the younger newer RC educators, but “whatever the middle group is, we don’t have a lot of these people stepping up.” This participant stated they felt this gap in leadership has been a “detriment to the field.”

Looking to the Future

Participants, in their discussion of the future, shared what they perceived to be challenges and opportunities for the field moving forward. They also shared their individual vision for the future of the profession. Three themes emerged: (a) clarifying our role and relationship with related professions; (b) recruitment, mentoring, and succession planning; and (c) increasing capacity for producing high-quality research.

Clarifying Our Role and Relationship with External Stakeholders

Respondents expressed an urgent need for rehabilitation counselors and rehabilitation counselor educators to articulate the services we provide and our role within the counseling field. An aspect of this means distinguishing ourselves from other counselors. Consistent with the divide observed in discussions of the present, respondents also differed in their vision of that role in the future. Several suggested RC should stick to what they perceived as “our roots” and focus on employment, independent living, psychosocial impact, and quality of life for individuals with disabilities. As part of this effort, respondents suggested we branch out to work with other counselors and, more broadly, other medical and human service professionals to define our role more clearly. One respondent described their experience:

I’m doing a lot of work in the cancer community right now, with social workers, psychologists, pastoral counselors, psychiatric nurses, nurse oncologists, and I’m the only person in the room that does career and vocational stuff, and they’re like, we need you. None of us do [this], so we need you.

Other participants suggested that, while RC may have disparate interests related to disability population and setting, the focus on psychosocial issues is a unifying feature to capture, “increasing our scope of practice so that we do focus more on the psychological impact, the mental health impact.” Another noted, “we should all focus on our strength, which is helping people become independent, quality of life, and employment.” A respondent explained their view on how to clarify our role with other counselors:

My vision for us is that we get back to our roots and focus on employment and independent living and disability issues, and the rest of the professionals learn how to work with the clients that we serve, and in doing so, helps us define who it is that we are because, by working more closely with us, they’ll understand when it is time to refer someone to us.

Several participants advocated for focusing on integrating with disability advocacy organizations and aligning ourselves with their priorities as central to our mission of serving individuals with disabilities. This would move us in the direction of fulfilling a shared value of addressing discrimination and stigma related to disability, factors that undermine work and life satisfaction. Several respondents noted their students have broad interests and are likely to take jobs in “non-traditional” RC settings. It is important for us to ensure they embrace our values and identify with our profession, with social justice and inclusion as the core. Participants felt this was a strength we could leverage to connect with other related professions:

A lot of different areas are talking about social justice, I think, which is the core of what we’ve been doing for years. So being able to better articulate that, I think, being able to help folks recognize how even disabilities occur, if we look at it from the populations that we work in even if you look from social justice perspective, it is your poor folks, the people who are doing the more manual labor still, so like other fields know all that stuff happens, but they don’t connect that back to disability.

What that identity should be remains an open question. One respondent offered, “we have to figure out what we are marketing before we start to market it. And it needs to be one voice.” Another described what is needed as “defining the brand” and not being too narrowly defined. Instead, balance the existing specialties with integrated practice, “multidisciplinary and intersectionality has to become part of the brand.”

Need for Advocacy. When discussing their vision for the future, multiple participants stated a need for us to focus more on advocating for the profession. Looking ahead, many suggested increasing our efforts in advocacy, and the critical responsibility of preparing students at all levels to be advocates. The National Rehabilitation Association Government Affairs Disability and Employment Summit was noted as an opportunity for counselors, students, and educators to engage with policy makers and elected officials. It remained unclear whether this opportunity is still available, and how well attended it is.

Role of Professional Organizations. Even though most did not agree on what our role, focus, or identity should be in their description of our vision, many respondents suggested professional organizations represent an appropriate venue to define it. Respondents expressed dissatisfaction with the current state of our organizations, stating there were too many, with too little participation, and too many divides for the size of our profession. There was general agreement that collaboration among leadership in the organizations would be an asset and vehicle to work out a unified message and engage in professional advocacy. One respondent described their view on our current state of disorganization:

Our strength would be in the collective. I think there are pockets of people who are standing and yelling: ‘Here is where we come in!’ ‘Here’s how we can help!’ ‘Here’s what we can do!’ And I think we need to figure out how to get back to being a more cohesive collective.

Another respondent described their vision this way:

Maybe that’s the place where our leadership could come together, as well. And then instead of having it come from one specific organization to put forward kind of the marketing is that everyone chips in. We hire an external person to kind of help us think about brand, think about how we talk about what we do, and then maybe we develop a joint 501(c)(3) that focuses just on the brand of rehabilitation counseling.

Recruiting, Mentoring, and Succession Planning

Participants expressed a need for greater attention to recruitment of master’s and doctoral students, as well as mentoring and succession planning to ensure a strong future. Several referenced newer professionals using terms like “bright” and “talented” and suggested we can tap into the potential of this new “generation” of professionals.

At the doctoral level, the issue of maintaining the available workforce was complicated by the shift in doctoral programs from CORE- to CACREP-accredited. This change mandated curricular shifts for many programs, and as described by some respondents, removed degrees of freedom in topics and training approaches. Several interviewees expressed concern that future faculty would not necessarily have experience in RC, or sufficient knowledge of disability issues to teach in CACREP programs moving forward. In their view, this could result in a loss of values and identity, and expertise in RC core topics (e.g., supported employment, independent living, psychosocial and vocational impacts) with broad impact for practice. Some individuals discussed the grandparenting clause for current faculty and recent graduates, but the expiration on this clause is impactful.

To recruit master’s-level practitioners, several respondents felt, if we could get the messaging right, our field could be an attractive option for recruiting young people. Particularly as disability becomes better recognized in society (e.g., through advertising, media, more open discussion of personal and family experience), we may be able to engage potential practitioners by emphasizing their ability to make a difference. A respondent described their view on how to recruit:

We need to find a way to help people feed their souls. And I think we’re off to a good start as a field. I think that we are engaged in a noble cause and a noble purpose, and I don’t just mean disability. I mean human rights. I mean access. I mean democracy. I’m talking big philosophical questions. Disability is a part of that.

To develop RC leaders, respondents expressed a need to enhance our efforts in mentoring and succession planning. Respondents expressed concern at the lack of engagement in leadership currently, and stressed the need to engage future leaders in these discussions. For example,

The best we can do is help guide the people. It’s really up to making sure that they have the tools they need, making sure that they have the connections they need, making sure they have a vision of what it is and not just kind of following whatever it is that we did.

Increasing Capacity for High Quality Research

Within their vision and plan shared for the future, several respondents mentioned increasing our capacity for high quality research. Respondents described a variety of priorities, using terms like “theory-driven”, “mechanistic”, and describing a need to employ experimental or pseudo-experimental designs, and increase our capacity for participatory action research and rigorous qualitative approaches. Our intervention research literature base has grown in the past decade (Fleming et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2021), but this continues to be an area where expansion is necessary. A need mentioned by several individuals was to continue to evaluate the efficacy of interventions, including increasing our understanding of overall effectiveness, as well as for specific populations and under different conditions. For example,

We need to continue to develop the capacity to do that high-level research, because without an evidentiary basis, we’re really just going off anecdote, gut feeling, and applying services, and I think that works great in some instances, but I think we really lose a lot of efficacy and a lot of overarching capacity if we don’t have that functional capacity.

A need for more advanced training in research and prolonged mentoring connections were suggested as a solution for increasing capacity in this area. For example,

We’re really not effective at mentoring up-and-coming scholars. I may work with people at my own institution or kind of look at stuff, things that are being worked on by some former doctoral students, but I do think a more developed formal mentoring process that’s available nationwide would be really useful.

Discussion and Recommendations

This study was an effort to understand the perspectives of mid-career rehabilitation counselor educators and scholars on strengths, assets, and a collective vision for moving the discipline forward in a productive way. These 14 individuals have been engaged in the field for an average of 27 years and are recognized for their contributions in rehabilitation counseling practice, leadership, service, education, and research. We used an appreciative inquiry lens to facilitate this investigation, though participants still provided a balance of strengths and barriers toward growth and stability for the RC profession. Themes did arise to help crystallize unique contributions and affirming values of rehabilitation counseling. While participants diverged in their vision for the discipline moving forward, key themes emerged as a foundation upon which to address some of the internal and external threats to the discipline, which have been recurring discussions in the literature.

From an appreciative inquiry approach and theme analysis, participants noted key action steps in their collective vision, including (a) increasing visibility and clarity of our role; (b) establishing relationships with other professions toward collective advocacy; (c) recruitment, mentoring, and succession planning for leadership; and (d) increasing capacity for high-quality research. Each action step will need specific strategies and focused efforts to address elements that serve RC well and the issues that need improvements.

Visibility and Clarity of Our Role

While participants did not suggest revisiting the merger, or continuing debate about professional identity, their comments reflected continued division on the conceptualization of the role of RC and scope of the RC profession. Two views emerged, which were consistent with essays and editorials provided shortly after the merger. Some respondents echoed views put forth by Strauser (2017), who argued that consequences of the merger were that it took us away from core vocational rehabilitation, private rehabilitation, and the intersection of disability, health, and employment. Others reflected arguments by Zanskas (2017), who suggested the merger solidified our place within the counseling field, and that our path forward is to get more involved with broader counseling and define our place. Fragmentation of the RC profession into many professional organizations has weakened our overall ability to advocate for the profession (McCarthy, 2020), and needs to be recognized as a barrier to moving forward with addressing issues of visibility and lack of clarity on what rehabilitation counselors are, and what we do. Following our professional timeline, identity debates are visible in our literature for nearly a third of our 100-year existence (Leahy & Szymanski, 1995). These internal struggles impede our ability to move forward as a strong collective.

Respondents, no matter their position, frequently cited the needs of persons with disabilities when detailing their vision for counselor role and scope. This can be the rallying point for RC identity: the value and tradition reflected within rehabilitation counseling and visible in our legislation is that our purpose has been, and remains, to serve individuals with disabilities. These statements aligned with recent writings by Bishop (2021), who argued the importance of considering the needs of individuals with disabilities, including the disproportionate impact of social and environmental problems on this population, as critical to our mission and our path to increased relevancy. Coalescing around this shared purpose provides a path to clarifying our professional role. If fragmentation of professional organizations has led to RC being “off message” and lacking influence in counseling and advocacy arenas, a consolidation or restructuring of professional organizations could lead to better focus, branding, vision, and leadership.

Finding Viable Partners Toward Collective Advocacy

An actionable step identified by respondents involves identifying and engaging with external partners aligned with RC’s goals of supporting persons with disabilities. This step depends on the success of clarifying our role, because, to borrow the word of one respondent, “we need to know what we are marketing before we market it.” As part of this effort, respondents suggested we branch out to collaborate with other counselors and other medical and human service professionals to increase our visibility. Others emphasized connections with disability advocacy organizations and aligning the RC profession with their priorities as central to RC’s mission of serving individuals with disabilities. Many rehabilitation counselors and researchers already collaborate with independent living partners, the Veteran’s Administration, the Department of Labor, and disability-specific service providers, and these are all viable connections that others may also consider.

Addressing Leadership Needs

A channel for strengthening professional organizations and ensuring their vitality is through sustained leadership. This requires recruiting and mentoring new generations of leaders across career phases in an intentional succession plan for shared governance. Several respondents noted a lack of engagement in leadership, and relatively few opportunities for developing scholars to engage in mentored leadership. This puts RC at risk for a leadership vacuum, as long-standing leaders retire without clear lines of succession. We emphasize that organizations need not be the only mechanism for leadership. Zanskas (2017) advocated for a servant leadership model, where all should be prepared to accept a stewardship role. While he suggested this should be approached organically, it needs to be a more intentional focus of instruction at the pre-service and doctoral training levels. Following curriculum-based introduction of leadership skills and values, programs should seek and utilize community- and university-based leadership mentors to foster these skillsets into relationships and action, based on the interests of the student and mission of the RC field.

Increasing Capacity for High-Quality Research

A final focus of action is toward high-quality research. Respondents’ feedback on the importance of strengthening research efforts moving forward was consistent with suggestions of Rumrill, Bellini, et al. (2019), emphasizing the need to continue to develop, assess, and refine evidence-based practices for application in RC settings. Participants aligned with these authors in their suggestions promoting enhanced training in qualitative techniques, experimental methods, and outcome research as essential for the future of the discipline. These suggestions are consistent with others who promote greater focus on intervention research as a necessary step in identifying evidence-based rehabilitation interventions (Phillips et al., 2021). An effective method in assisting doctoral students and new faculty in developing their research is mentoring (Ransdell et al., 2021). Though doctoral students typically enter with a research-focused RC or related master’s degree and a varying amount of practical experience, the skill set required to advance a research agenda involves a completely different kind of training. Typical program length for a Ph.D. program is three to five years, which may not be enough time to fully develop research skills and capacity, along with other program requirements. Mentoring in specific skills, such as manuscript and grant writing, project management, and data analysis, is likely to help students and graduates further develop in these essential areas, leading to increased capacity for independent research. Additional mentoring in more general research topics, such as generating productive collaborations and effectively responding to criticism, may also be useful (Ransdell et al., 2021).

Limitations

The results of this study must be considered within the context of several limitations. Related to sampling, we must acknowledge that both snowball sampling and purposive sampling can lead to sampling bias of potential participants, as the initial participants may choose participants who are like themselves and may not be representative of the larger population. Additionally, individuals on the project research team were nominated across categories by others to be participants themselves, but due to their involvement in the study, could not also be participants. Our interview and coding team engaged in a reflexivity process, but other coders may have approached interviews and analyses with different biases and expectations, and therefore may have reached different conclusions. While we believe our approach and sample was appropriate given our questions, other participants may have provided different views that were not captured by our study.

Conclusions

The findings of this study reflect the unique characteristics of the RC profession, as well as echoing some that are well known and documented. Though, ultimately, the participants in our sample observed several strengths, points of pride, and distinct assets of RC. They expressed views that reinforce our viability and contributions to serving individuals with disabilities, as well as other possible clients, with high levels of skill and effectiveness through our strong training. Participants complimented the people associated with rehabilitation counseling, highlighting them as an asset at several opportunities. Despite these strengths, participants also highlighted missed opportunities and necessary areas of growth to ensure continued viability of the discipline in the future. These were translated into suggested actionable steps for the discipline to consider improving our future standing, presented without endorsement of order or priority.