Professional associations exist to meet the needs of their constituents and to professionalize a discipline—and rehabilitation counseling’s associations are unwell. This fact is not new, although it may feel that way to the many rehabilitation counselors who have not been monitoring them or to the few who appreciate the cohesiveness that is enjoyed in an association that is limited in numbers. For decades, leadership in rehabilitation counseling has expressed concern over declining membership numbers and debated the wisdom of multiple associations representing our relatively small discipline (Emener & Cottone, 1989; Leahy & Tarvydas, 2001; Nadolsky, 1981; Rasch, 1979; Reagles, 1981; Roberts, 1981; Rubin, 1981; Shaw et al., 2006). Problems that were first appreciated in the late 1960s and early 1970s have not abated. However, it appears by the limited amount of action in recent years that interest in the topic clearly has. At this point, there is little question that the weakness of rehabilitation counseling professional associations is limiting the progress and professionalization of rehabilitation counseling professionals, as predicted (Emener, 1981; Leahy et al., 2011).

The articles in this special issue provide an extensive, forward-thinking exploration of actions that can be taken to have the strong association representation that is so desperately needed in an era of deprofessionalization and political agitation (Phillips, 2011). Notably absent from the literature are the perspectives of the rehabilitation counseling professional the associations are intended to represent. Dr. William G. Emener, professor and editor of the last special issue to focus on rehabilitation counseling professional associations in 1981, recognized this as a critical next step in determining the future of the associations. As a summative statement for the entire special issue, Emener (1981) said:

In conclusion, we need to act. At least we still have some choices. If we wait and continue to deliberate, it simply may be too late. However, before a few dozen of us decide and act, it may be beneficial to put the issues and questions to the members (e.g., the 20+ thousand NRA [National Rehabilitation Association] members). In an age of consumerism, why not poll the opinions of our constituents? (p. 94)

A critical foundation for this special issue centers on the quantitative and qualitative insights obtained through surveying 2,608 rehabilitation counseling professionals. Before outlining the articles in this special issue, we provide important context for considering the future of rehabilitation counseling professional associations. We also address common misconceptions that seemingly drive the apathy and ignorance experienced towards associations in the discipline. In an era of social media and online communities, professional associations may feel antiquated or irrelevant. This idea would make sense if professions were standalone institutions that grew merely from a shared interest. However, professions rely on a system of structures to create a shared identity, regulate practice, and act on behalf of the larger group and the society. Professions are represented by individuals sharing a common knowledge, skills, and values. Beyond this, a profession’s ecosystem includes (a) regulatory bodies that are intended to protect society by maintaining standards of quality in training and service provision and (b) professional associations that are intended to further the self and other interests of the profession. The health of each part of the professional ecosystem is critical to the overall health of the discipline it represents. We proceed with a brief overview of professional associations and their important role in a profession.

The Role of Professional Associations in a Discipline

Professional associations are non-profit organizations tasked with representing and carrying out the interests of a profession (Emener, 1986; Goode, 1957; Leahy, 2004; Leahy et al., 2009; Miller & Chorn, 1969; Sussman et al., 1965; Sweeney, 1995; Tarvydas et al., 2009). In this capacity, professional associations act as a primary influence in the professionalization (or deprofessionalization) of an occupation (Heinemann et al., 1986; Rollins et al., 1999; Sussman et al., 1965, 1966). Professional associations provide a source for professional definition (Bucher & Strauss, 1961; Tarvydas & Leahy, 1993; Yeager, 1981), increased public awareness (English, 1940; Goode, 1969; Patterson, 2009), and play a critical role in securing a discipline’s right to practice (Noordegraaf, 2007; Tarvydas et al., 2009).

The functions of a professional association also typically include creating ethical codes of practice (Moore, 1970; Tarvydas & Cottone, 2000), facilitating skill development through training and continuing education (Karseth & Nerland, 2007; Leahy, 2002), setting standards for education and practice (Sussman et al., 1965), unifying political action (Rieger & Moore, 2002), and providing a general forum for intraprofessional communication (Greenwood et al., 2002; Hovekamp, 1997; Leahy, 2004; Moore, 1970; Rieger & Moore, 2002; Wright, 1974). After listing the many critical roles professional associations play, it is easy to appreciate that the health of a discipline’s professional associations is closely tied to the professionalization of that discipline.

Assessing the Strength of an Association

The strength and viability of a professional association can largely be measured by the number of professionals who hold membership and participate in that association (Allan, 1963; Brabham, 1988; Mills, 1980; Oliverio, 1979; Patterson & Pointer, 2007; Whitten, 1961). Associations rely on the coproduction of their members to create value and to meet the objectives of a discipline (Gruen et al., 2000; Williams, 1977). For this reason, associations are of the most value when membership is high and when a high proportion of that membership is engaged through service, advocacy, and the dissemination of information. One additional indicator of an association’s strength is captured in what Merton (1958) termed a completeness of membership. Completeness of membership exists when a high proportion of the targeted population for a given association maintains membership in that association. A completeness of membership increases the likelihood of professional associations accurately representing the needs and interests of the diverse constituencies they serve (Moore, 1970). An association that fails to attract and enfranchise a high proportion of professionals, or one that systematically cannot enfranchise subpopulations of their constituency, risks being misinformed and misguided in the action it takes.

In summary, the strength of an association is dictated largely by (a) the raw number of members it attracts, (b) the engagement of those members, and (c) the overall completeness of membership from the discipline it represents.

Rehabilitation Counseling Professional Associations

The beginning of rehabilitation counseling associations can be marked by the creation of the National Rehabilitation Association (NRA) between the years 1923 and 1925 (originally called the National Civilian Rehabilitation Association; Emener, 1986; Lamprell, 1975; Sussman et al., 1965; Whitten, 1958). The NRA originally viewed state-federal rehabilitation counselors as their primary constituency. In fact, a person had to be a state-federal rehabilitation counselor to be a voting member in the first years after the NRA was formed (Sussman et al., 1965; Whitten, 1975). The NRA played a crucial role in the early years of the fledgling occupation. Whitten (1958) credited the NRA with keeping the “rehabilitation idea” alive in the first decades of rehabilitation counseling, as well as providing key advocacy in important legislation, such as the Barden-LaFollette Amendments of 1943. As important as NRA has been to the discipline, over time, the organization broadened its representation beyond a professional rehabilitation counseling association to include any professional viewing themselves as being in a rehabilitation discipline, as well nonprofessionals with an interest in issues related to disability (Hanson, 1970; Whitten, 1959). The NRA would later revise their mission statement to suggest their constituency includes professionals in rehabilitation (Sales, 1995). However, the expansion beyond rehabilitation counseling meant there was no longer a professional association directly and solely representing rehabilitation counselors.

Rehabilitation counseling was again directly represented in 1958 with the formation of not one but two professional associations, the National Rehabilitation Counseling Association (NRCA) and the American Rehabilitation Counseling Association (ARCA). NRCA was formed in October 1958 under the original title of the Rehabilitation Counseling Division of NRA (Sussman et al., 1965). This name was later changed to NRCA in 1963. ARCA was also officially formed in 1958 as the Division of Rehabilitation Counseling under what was then called the American Personnel and Guidance Association (later to be known as the American Counseling Association [ACA]; Sussman et al., 1965). This division changed its name to the present ARCA in 1961 (Sussman et al., 1965). ARCA and NRCA were strategically created to represent complimentary constituencies of rehabilitation counseling under the assumptions that this dual representation most accurately captured the dual nature of the discipline (Leahy & Szymanski, 1995; Thoreson, 1971). These two rehabilitation counseling associations worked closely together in the first decades of being established to help create the professional ecosystem for the discipline. This included the creation of the Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC), a national organization for certifying rehabilitation counselors, and the Council on Rehabilitation Education (CORE), a now defunct organization for accrediting rehabilitation counseling training programs (Miller & Chorn, 1969; Wright, 1974). Both associations also worked with the CRCC to create a unified code of ethics for the discipline (Tarvydas & Cottone, 2000). These and other early milestones in the professionalization and external representation of rehabilitation counseling have shaped the discipline to what it is today.

Historically, state-federal rehabilitation counselors affiliated primarily with NRCA and those outside of the state-federal system split between ARCA and NRCA (Allan, 1967; Emener, 1986; Hanson, 1970; Irons, 1989; Jaques, 1959; Sales, 1986; Sussman et al., 1965). ARCA membership has also tended to include a higher proportion of academics than NRCA (Cook, 1990; Trotter & Kozochowicz, 1970). The leadership for ARCA and NRCA has historically been even more split than its membership, with state-federal administrators leading NRCA (Allan, 1967) and rehabilitation counselor educators leading ARCA in the first decades after their establishment (Feinberg, 1973; Jaques, 1967; Thoreson, 1971). Over time, differences between ARCA and NRCA membership and leaders appear to have become somewhat less prominent, as have the differences in their overall missions and objectives.

Today, ARCA continues to exist as a division under its parent organization, ACA. NRCA existed as a division under its original parent organization, the NRA, until 2005 when it broke off to form an independent association after failing to agree on terms of its division status (Leahy, 2009). In 2006, the NRA created the Rehabilitation Counselors and Educators Association (RCEA) to replace NRCA as the NRA division most closely representing the discipline of rehabilitation counseling. Citing declining membership and financial difficulties, NRCA presented its membership with options for moving forward (NRCA, personal communication, August 29, 2016). Less than two months later, membership was informed that over 67% were in favor of realigning under NRA through a merger with RCEA (NRCA, personal communication, October 19, 2016). The president of NRA sent out a welcome email to NRCA membership within the week and, for a short time, both NRCA and RCEA were listed as divisions on NRA’s website (NRA, personal communication, October 24, 2016). However, once again, negotiations broke down over the terms of divisional status, and NRCA opted to recreate their status as an independent association, which is how the associations (more accurately termed association and divisions) are aligned today (NRA, personal communication, March 12, 2019).

Before discussing membership trends for ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA, it is important to highlight the fact that many other associations and divisions play an important role in the discipline. These include the International Association of Rehabilitation Professionals (IARP), National Association of Multicultural Rehabilitation Concerns (NAMRC), Vocational Evaluation and Career Assessment Professionals Association (VECAP), Vocational Rehabilitation Association of Canada (VRA Canada), Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities (JSRPD), and National Council on Rehabilitation Education (NCRE). The focus on ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA stems from the fact that these three entities have historically been accepted as broadly representing the rehabilitation counseling discipline in the U.S., whereas the others have historically represented a specialization of the discipline or other locations in the world.

Membership in Rehabilitation Counseling Associations

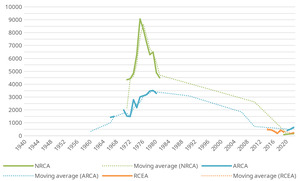

As noted previously, membership plays an important role in the strength and value of a professional association. The raw number of association members for ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA are presented in Figure 1. Some years represented by the dotted lines are not known because the corresponding association no longer had the data, and no reports of membership numbers could be found in the literature for that year.

NRCA experienced its greatest number of members in 1975 when it had 9,071 members; in 2022, NRCA reported 159 members (Field, 1981; NRCA, personal communication, March 15, 2022). ARCA membership peaked in 1979 at 3,512 members (Field, 1981; Phillips, 2011). In 2022, ARCA reported 652 members (ARCA, personal communications, March 2, 2022). With RCEA coming onto the scene more than three decades later, the difference between the peak (n = 467 in 2014) and the present (n = 232 in 2022) is less pronounced (RCEA, personal communications, April 20, 2022). To put these numbers in context, Brubaker (1981) argued that 10,000 was the minimum number of professionals needed in an association to compete for recognition.

Despite ARCA’s and NRCA’s steep declines, membership among their original parent organizations (ACA and NRA) has diverged over the years. NRA membership peaked in 1974 with 35,257 members, with about half of those members being non-professionals (Field, 1981; Whitten, 1961). It is also worth noting that this number has been accused of being at least somewhat inflated (Sales, 1995). ACA membership has followed more of a linear, upward trend. In 1975, near NRAs peak, ACA reported having 40,641 members, while in 2022 they reported having 58,000 (ACA, Personal communication, January 25, 2022).

Completeness of membership also tells an important story of rehabilitation counseling associations. In 1965, Sussman et al. crossmatched the list of all state vocational rehabilitation counselors (N = 3,610) against association membership lists for ARCA and NRCA. He found that 2,303 (62.5%) state vocational rehabilitation counselors held membership in at least one of the two associations. It is interesting to note that this data came one year before the Council of State Administrators of Vocational Rehabilitation (CSAVR) entered a formal partnership with NRA that, among other things, led to increased support for membership among state vocational rehabilitation counselors (Hanson, 1970). Although not a perfect comparison, in 2012, Phillips and Leahy estimated the percentage of certified rehabilitation counselors in one of the three associations to be no higher than 11% and possibly much lower. In summary, the last several decades have shown a decline in membership and in membership completeness, and this decline has been a continuous concern for the discipline (Bain, 1977; Emener, 1986; Oliverio, 1980; Shaw et al., 2006).

Common Misconceptions and Barriers to Becoming Informed and Taking Action

Given the lack of momentum built over decades of declining membership, we share a few of the common misconceptions, beliefs, and barriers that seem to be limiting our ability as a discipline to take action to address it. These include (a) the belief that associations are irrelevant to the everyday issues professionals face, (b) refusing to join unless and until the association offers sufficient value, (c) a belief that markets will correct themselves if needed, (d), a belief that having a choice benefits the consumer, (e) hopelessness that things can change, and (f) the idea that association leadership’s primary responsibility is to the association. We will briefly address each of these misconceptions or barriers.

Because of the close relationship between the belief that professional associations, or at least rehabilitation counseling professional associations, are irrelevant and the belief that one should not join an association unless it offers sufficient value, we consider these together. Many professionals in the discipline have heard statements like, “I could care less about associations. All I really care about is gaining access to licensure in my state,” or “I am not wasting my money on association membership when what I really need is a pay raise.” These statements neglect the fact that associations are the primary vehicle for addressing these types of concerns. Any problem or opportunity that is common to rehabilitation counselors is a problem or opportunity that professional associations were created to address. When we accept the misconception that associations are irrelevant, we unintentionally cut off the most likely source for addressing the issues, needs, and concerns professionals experience in their work.

Some will predictably counter that the associations lack relevance because they lack the ability to address the needs of greatest priority to the rehabilitation counseling professional. This view of irrelevance is a statement of value, or more accurately, a lack of value in holding membership. As stated previously, associations generate value from having a high number of engaged members. Therefore, a professional who chooses not to join an association because it fails to provide value helps to ensure that it will not provide value in the future. This is the sticky problem for associations with few members like ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA, and there is reason to question whether associations have consistently reacted effectively. In the face of declining membership, the most common response has been to attempt to identify, market, and enhance incentives for joining (e.g., Cook, 1990; Huber et al., 2019; Jones, 1986, 1995; Kauppi, 1975; Kirk & La Forge, 1995; Peterson et al., 2006; Phillips, 2011; Trotter & Kozochowicz, 1970). Attempting to create added value when the members who generate it are leaving is difficult to impossible. Perhaps even more concerning, when leadership seeks to reverse declining membership by adding tangible benefits, it reinforces the idea that professionals are consumers who should wait until the return on investment justifies joining. A better approach is to remind professionals of the incredibly important role associations play in meeting the needs of the profession and those who work in it and invite them to join in an effort to create the value and relevance they seek, which the discipline so desperately needs.

An additional source of apathy stems from a passive trust in the market to correct itself if associations are not structured effectively and efficiently. This misconception applies to the debate around consolidation. Working from this belief, professionals seem to expect that an association will go away if it is no longer able to provide the service(s) it was created to perform. Relatedly, professionals may belief that, if there are too many associations, the market will correct itself by causing one or more to shut down. This misconception about the labor market in relation to professional associations is understandable. After all, most of us have seen a restaurant with poor service fail due to competition from a restaurant that provides better service. However, examples from for-profit entities do not translate as naturally to non-profit professional associations. If we have learned nothing else from the past 40 years of steep membership declines, it is that professional associations are resilient to market forces. When membership revenues and resources decline, associations tend to evolve rather than exit the market. This is possible because associations can survive using a foundation of volunteers who are reinforced (especially in academe) for keeping them running. Thus, it is highly unlikely for the free market to dictate which associations should and should not continue to exist, even if they are no longer capable of performing the mission they were created for—to represent rehabilitation counselors. If it becomes clear that an association is failing to fulfill its purpose or that it is inefficient in doing so, change will require a proactive effort from professionals in the discipline.

A separate misconception about the free market is that numerous professional associations create competition that is inherently good for the profession. Under this false belief, a single, unified association may represent a loss of choice inherently bad for the discipline. At the creation of ARCA and NRCA, the intention was for them to be complementary rather than competitive. So, in free market terms, it is better to think of ARCA, NRCA, and now RCEA, as three separate shops owned by the same entity (the entity is the discipline of rehabilitation counseling). Viewed this way, the value of choice over unity hinges on whether ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA all target the same customers with the same products or benefits, or whether they each play a unique role in the discipline. If they target the same customers with the same products or benefits, having more than one association not only fails to provide meaningful choice but also creates inefficiencies and confusion that can weaken the associations in their ability to represent the discipline. Even among those who see uniqueness in the missions of the three rehabilitation counseling associations, it is valid to question whether there are enough potential constituents to keep them all running effectively.

Another barrier to action comes from the belief that change simply is not possible. These ideas are most likely to be held by those familiar with failed efforts to rethink rehabilitation counseling professional associations in the past or from professionals who have served in association leadership positions and witnessed first-hand the challenges and complexities of making significant change. This barrier dovetails with the misconception that association leadership’s primary responsibility is to the association. The idea that any major change, even one that is desired by constituents and that would strengthen the discipline, is not possible flies in the face of reason. Associations exist to provide value to the discipline and to the constituents they represent (Obermann, 1957). Any rehabilitation counseling professional who argues that efforts to professionalize the discipline are not possible because of complexities in our associations is allowing the tail to wag the dog. One thing this special issue offers that previous efforts to act have not is empirical data reflecting the perceptions of rehabilitation counseling professionals. It is hoped that this will provide association leaders the data they need to represent their constituents in shaping the future of the associations.

The Current Special Issue

In this special issue, we present data and discussion fueled primarily by the perspectives of 2,608 professionals connected to the discipline of rehabilitation counseling. In the first article, Phillips, Walker et al. (2022) share quantitative results addressing the primary question of whether members of the discipline favor or oppose consolidating rehabilitation counseling professional associations. Results showed that 46.6% favored consolidation while only 7.0% were opposed. The remaining 46.4% reported being unsure. Phillips, Walker et al. conclude the results by exploring factors that may influence perceptions of whether to consolidate. In the next article of the special issue, Nerlich et al. (2022) provide a qualitative analysis of the rationales provided by rehabilitation counseling professionals for their choice in favor of, opposed to, or unsure about consolidation. They found that a significant majority of those reporting they were unsure about consolidation lacked familiarity with the associations or with the debate about consolidating them. Among those favoring consolidation who also provided a rationale (n = 1,033), the most common rationales were the perceived internal unity, a strengthened external voice, and the economic and administrative benefits that consolidation would provide. For those opposed who provided a rationale (n = 138), a perceived loss of identity, general contentment with or apathy over things as they are, and the benefits of having options were the most cited.

In the next article by Landon et al. (2022), authors build on the finding that most rehabilitation counseling professionals with a strong opinion favor consolidation by exploring who to consolidate and how it might be accomplished. Their findings suggest that participants tend to support a consolidation effort that extends beyond ARCA, NRCA, and RCEA to include, at the least, the private sector and NCRE. Responses on how participants would prefer to consolidate rehabilitation counseling professional associations showed that 30.9% had no opinion. Among those who did, the greatest percentage favored creation of a new, freestanding association (25.8%) followed by the preference to consolidate under NRCA (17.3%) or under ACA as ARCA or by another name (15.5%). Qualitative suggestions for the process of pursuing collaboration are also analyzed and shared. Levine et al. (2022) used a mixed-method approach to consider how diversity, equity, and inclusion might be incorporated into a consolidated association. Their findings show that a majority (64.4%) of respondents favor inclusion of a division or emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion in a consolidated association, while 26.7% were unsure and the remaining 9.0% were opposed. Closer examination of the data highlighted factors that predicted the perceptions on including diversity, equity, and inclusion. Qualitative analysis further illuminates the rationale behind participants’ choices, with results showing a clear divide in how rehabilitation counseling professionals view the place of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the field and, more specifically, in our associations.

Phillips, Gerald et al. (2022) consider the potential effect of consolidation on membership in the article that follows. The Net Promoter Scores for the current associations were compared with Net Promoter Scores for a hypothetical association. Findings suggest that consolidation would be accompanied by a substantial increase in the early promotion of a consolidated association. Elevated promotion for a consolidated association compared to the current associations existed for those who currently hold membership in at least one of the rehabilitation counseling professional associations, as well as those who do not identify with any of them. In the final article of the special issue, Hartley and Saia (2022) provide a theoretical consideration of how rehabilitation counseling professional associations should collaborate with and situate themselves in relation to the disability community. They begin by providing a brief history of social action in rehabilitation counseling professional associations and make a strong argument for re-engaging in social action and amplifying the voices of disabled people. They conclude with asking some pointed questions for reflection and providing initial steps associations can take to accomplish these objectives. The special issue concludes with an attempt by Phillips, Boland, Zanskas et al. (2022) to summarize the findings and implications contained in the special issue.