With millions of United States troops having been deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, the need for rehabilitation and mental health services for service members returning from active-duty military service has increased dramatically. To the credit of advancements in health and military technology, more veterans are able to survive from severe injuries; however, these veterans may live with severe disabilities (e.g., polytrauma), which may be challenging for rehabilitation and mental health counseling processes.

Disability, poverty, homelessness, and unemployment are significant challenges for veterans with disabilities, their families, service providers, stakeholders, and policymakers. Research has long identified employment and rehabilitation services can buffer against poverty, homelessness, and unemployment among people with disabilities, including veterans with disabilities. Yet, VR services are identified as the least used VA services among veterans (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b). Therefore, in this study, the aim is to inform clinicians and researchers on employment and rehabilitation services, including Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) for veterans with disabilities. More specifically, with this study, first sociodemographic, disability, health, and service-use characteristics of veterans will be introduced. Next, strengths of employment and rehabilitation services, challenges for VR and VA agencies and veterans with disabilities, and opportunities to improve VR services will be overviewed.

Sociodemographic, Disability, Health, and Service-Use Characteristics of Veterans

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, based on 38 U.S.C. § 101(2), the term veteran means “a person who served in the active military, naval, or air service, and who was discharged or released therefrom under conditions other than dishonorable” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019b, para. 3). The weighted estimate of the number of veterans is 18.3 million, of which 1.6 million are women (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). Compared to the non-veteran men percentage (45.3%) in the general population, veterans are predominantly men (approximately 91%), meaning that women are underrepresented in the veteran population (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016, 2019a). It is also important to note that veterans are significantly older than the non-veteran population (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b). Additionally characteristics, such as employment, disability, and income, will be significantly impacted due to this age differences between the two groups (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016, 2019a).

Regarding race and ethnicity, 77.7% of veterans are White (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016). VA reported that 7.1% of male veterans (19% of male non-veteran) and 9.5% female veterans (16.6% female non-veteran) are Hispanic, meaning there are fewer Hispanic male and female veterans compared to their non-veteran counterparts (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). The veteran population does not have a high minority composition. According to the VA, only 23% of veterans are minorities compared to 37% of non-veteran minorities (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). Black or African American veterans (12%) and Hispanic veterans (7%) are the two largest minority veteran groups (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). Female veterans were more likely to have some college and bachelor’s degree and an advanced degree compared to male Veterans and female non-Veterans (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a).

Chronic Conditions, Disability, and Service Use among Veterans

Veterans Affairs assigns a disability rating to a veteran based on the severity of their disability (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022a). While 21.8% of veterans have service-connected disability status, 34.1% of those veterans have a 70% or higher disability rating (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016). Furthermore, female veterans (25.1%) reported higher-service connected disabilities than male veterans (22.8%) (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). Nevertheless, when looking at the VA benefit utilization statistics, approximately 100,000 veterans received VR services (e.g., Compensated Work Therapy [CWT]) from the VA in FY 2017, even though 9.8 million veterans used at least one VA benefit or service the same year (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). CWT is a vocational rehabilitation service through VA helping veterans with disabilities obtain competitive employment (Cosottile & DeFulio, 2020). In addition, it is anticipated the percentage of disability could be higher for veterans, given that many do not seek help when experiencing mental health symptoms. Therefore, this service-connected disability data from the VA only includes veterans who received services from the VA.

Most importantly, the VA reported that “the likelihood of [a Veteran with disability] seeking treatment from a VA Health Care facility, varied with race and ethnicity; however, rates for Black or African American, Hispanic, and AIAN [American Indian or Alaska Natives] were higher than the overall rate of VHA usage” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a, p. 40). For example, 67.6% of White veterans with service-connected disabilities used healthcare services, compared to 77.4% Black or African American veterans with service-connected disabilities, 62.5% of Asian veterans with service-connected disabilities, 70.9% AIAN veterans with service-connected disabilities, 66.5% Native Hawaiians and/or other Pacific Islander veterans with service-connected disabilities, and 71.5% Hispanic veterans with service-connected disabilities (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). In FY 2009, characteristics of sheltered homeless individual veterans identified 51.2% with disabilities (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2012), meaning that disabilities among homeless veterans are very common.

Employment, Poverty, and Homelessness among Veterans

Veterans are more likely than the non-veteran population to experience employment difficulties (Cosottile & DeFulio, 2020). According to the VA, only 44.2% of veterans are employed, which is lower than non-veterans (61.2%; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016). Black or African American veterans (3.3%) were more likely to have lower unemployment rates compared to their non-veteran counterparts (5.0%). Data also revealed that minority veterans were less likely to live in poverty compared to non-veteran minorities (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019a). Data also revealed that male veterans had a higher median household income than female veterans. Homelessness is a significant public health and rehabilitation concern among veterans. According to VA data, 16% of the homeless population are veterans despite only 10% of the total population being veterans, meaning veterans are overrepresented among the homeless population (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2012).

Employment and Rehabilitation Services for Veterans with Disabilities

Veterans with disabilities (e.g., service-connected disabilities) may receive VR services from both the VA and state VR agencies. The four most common VR services for veterans with disabilities are Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment, the Compensated Work Therapy Program, State Vocational Rehabilitation Programs, and Community Rehabilitation Programs.

Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (VR&E), referred to as the Chapter 31 program, provides VR services to eligible service members and veterans with service-connected disabilities to help them prepare for, obtain, and maintain suitable employment or achieve independent living (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015). Not every veterans and service members with a service-connected disability is eligible for these services. According to VA policy, there are eligibility criteria for veteran and service members (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015). For veterans, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2015) reported that “A Veteran must have a VA service-connected disability rating of at least 20 percent with an employment handicap, or rated 10 percent with a serious employment handicap, and be discharged or released from military service under other than dishonorable conditions (para. 2).”

For service members, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2015) reported that “Service members are eligible to apply if they expect to receive an honorable discharge upon separation from active duty, obtain a rating of 20 percent or more from VA, obtain a proposed Disability Evaluation System (DES) rating of 20 percent or more from VA, or obtain a referral to a Physical Evaluation Board (PEB) through the Integrated Disability Evaluation System (IDES) (para. 3).” VR&E has services based on needs of veterans and service members with disabilities. VR&E has five tracks to employment, which “provide greater emphasis on exploring employment options early in rehabilitation planning process, greater informed choice for the Veteran regarding occupational and employment options, faster access to employment for Veterans who have identifiable and transferable skills for direct placement into suitable employment, and an option for Veterans who are not able to work, but need assistance to lead a more independent life” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015, para. 5).

The Compensated Work Therapy (CWT) Program is a VA clinical vocational rehabilitation program (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020a). CWT professionals provide (a) evidence-based vocational rehabilitation services; (b) partnerships with business, industry, and government agencies to provide veteran candidates for employment and veteran labor; and (c) employment supports to veterans and employer. The mission of CWT mission is to match veterans’ skills, abilities, and preferences, and help them find employment. CWT staff develop partnership with organizations, companies, and government agencies who need employees with proven abilities to produce high quality work. Unlike VR&E, CWT programs are located in all VA medical centers.

Unlike other individuals with disabilities, veterans with disabilities may seek VR services from both the VA CWT programs and state VR programs in their residence state. The eligibility for veterans to participate in state VR and employment services may change from state to state. Therefore, it is important to note that the collaboration between state VR programs and VA VR programs could improve employment outcomes for veterans with disabilities. For example, perceptions of state VR agency administrators on State Vocational Rehabilitation Agencies (SVRA) and VA VR&E programs were examined and it was identified that co-service practices could improve employment outcomes among minority veterans with disabilities (Johnson et al., 2017).

Finally, veterans with disabilities may receive VR services from community rehabilitation programs (CRP). CPR are community-based nonprofit private or government entities providing mental health, rehabilitation, employment, and independent living services. CPR staffs may provide vocational evaluation, community-based assessment, job development, and job coaching services to veterans with disabilities.

Overall, veterans with disabilities have unique sociodemographic, disability, and health factors, which also affect their service-use behaviors. When looking at Rehabilitation Service Administration (RSA) data, the number of veterans who applied to VR services through state VR agencies was 9,606 in first three quarters of Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, which is 24% (n = 7,729) more than the first three quarters of FY2016. This data indicates that State VR service use has substantially increased among veterans with disabilities, demonstrating that more attention should be given sociodemographic, disability, health, and service-use characteristics of veterans. Given there are multiple employment and rehabilitation services options for veterans with CID, it is important for policymakers to develop health policy and administration strategies to have a well-coordinated and efficient employment and rehabilitation services for veterans with CID. The following section will cover strengths and benefits of VR services and programs for veterans with disabilities.

Strengths and Benefits of VR Rehabilitation and Employment Services and Programs for Veterans with Disabilities

Previous literature has documented well the benefits and strengths of employment and rehabilitation services and programs for veterans with disabilities. The common consensus of these studies is that employment and rehabilitation services improve employment and rehabilitation outcomes among people with disabilities, including veterans with disabilities. In this section, some works documenting the importance and strengths of employment and rehabilitation services including VR services for veterans with disabilities will be reviewed.

In a recent study, Shepherd-Banigan and colleagues (2021) examined experiences of veterans with disabilities who use VA vocational and education training and assistance services, such as supported employment, education benefits, and VR&E, and their caregiving needs. The authors conducted 26 joint semi-structured interviews with post-9/11 veterans who had used at least one of three vocational and educational services, as well as the veterans’ family members who were enrolled in a VA Caregiver Support Program. Researchers conducted applied thematic analysis to analyze participants’ responses. Their findings revealed that participants perceived that VA vocational and educational services have the potential to improve successful integration into the civilian workforce among veterans. Participants reported that VA services and benefits helped them develop new skills, qualifications, and networking opportunities to secure a job that accommodates their disabilities.

In another study, Resnick et al. (2006) examined what makes VR effective by looking at VA program characteristics and employment outcomes at the national level. Specifically, they examined (a) the diversity of programmatic elements among VA CWT programs, (b) client-level predictors of employment success at discharge, and (c) the association between programmatic features and success. Their results revealed that, when compared to individuals working in a workshop, veterans who joined in community-based [transitional work experience] were over 2.5 times more likely to be discharged to competitive employment, over twice as likely to be discharged to any kind of constructive activity, and 1.6 times more likely to be discharged “successfully,” when all other individual-level and programmatic variables were controlled. The authors reported that only 15% of veterans participated in community-based work activities, though this was the strongest predictor of success at discharge. Regarding program-related variables, program structure, program focus, or facility support were not significantly related to outcomes; however, they reported that assertive outreach to engage veterans in the program was significantly related to both competitive employment and constructive activity at discharge. Overall, the authors reported that VA VR services should focus more on community-based vocational services instead of institution-based workshop programs.

Webster et al. (2018) developed the Servicemember Transitional Advanced Rehabilitation (STAR) Program, a novel residential VR program for injured service members and veterans. They recruited a total of 102 service members and veterans with injury to test their program. Authors reported that those who joined in STAR program had significant improvements in physical, mental and emotional, and vocational functioning.

O’Connor et al. (2016) examined a 12-week cognitive rehabilitation intervention embedded within VR services for veterans with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and mental illness. Their results revealed that competitive employment rates were higher among participants who received this 12-week embedded program compared to control group who received client-centered therapy that did not focus on employment or cognitive rehabilitation. Those who received the 12-week cognitive rehabilitation intervention embedded within VR services had improved days worked, hours worked, and money earned.

Employment and rehabilitation services and programs show promise in veterans with felony history, as well. LePage et al. (2018) compared three different vocational reintegration modalities (i.e., basic service, self-study using the About Face Vocational Manual, and the About Face Vocational Program) for veterans with felony histories. Their results revealed that receiving a standardized group-based program (i.e., the About Face Vocational Program) had better outcomes than basic services or the self-study program over a one-year follow-up period. For example, the authors found those with standardized group-based program were almost twice as likely to find competitive employment within a year. Participants who joined group-based program were also over three times as likely to have achieved stable employment as those in the basic services condition and over seven times as likely to achieve stable employment as those in the self-study condition. Another study conducted by LePage et al. (2016) examined the six-month outcomes of incorporating the principles of supported employment into the About Face Program for formerly incarcerated veterans. They randomly assigned veterans to either the About Face Program (AF) or to that program plus a modification of Individual Placement and Support (IPS+AF). They followed veterans after six months and found that employment rates were significantly higher for veterans who received AF+IPS, with 46% finding employment compared to only 21% who received AF only.

In addition to research on VA VR services and programs, there are also studies examining state VR services for veterans; however, studies examining the effectiveness of state VR services for veterans are limited. Moore et al. (2015) examined return-to-work outcome rates of African American and White veterans served by state VR agencies to identify disparities based on race, gender, and level of educational attainment at closure in veterans. The authors used the RSA-911 database for FY2013. Their results revealed that “(a) the odds of White veterans successfully returning to work were nearly 1½ times the odds of African American veterans returning to work and (b) African American female veterans had the lowest probability for successfully returning to work. Moreover, findings indicated that African American veterans’ successful return-to-work rates in 5 of the 10 RSA regions were below the national benchmark” (pp. 158).

Barriers, Challenges, and Needs in Successful Rehabilitation and Employment Services and Programs

In addition to employment barriers due to disabilities, veterans with disabilities also experience barriers and challenges while using or seeking rehabilitation and employment services. In this section, certain barriers, challenges, and needs in successful employment and rehabilitation services and program for veterans with disabilities are addressed.

Shepherd-Banigan et al. (2021) examined facilitators and barriers of VA vocational and educational service use among veterans with disabilities. Their results revealed that health problems, VA bureaucratic processes, and VA and academic programs that did not accommodate the needs of veterans with disabilities were the most cited barriers among veterans with disabilities who experienced challenges. Another barrier was concerns about benefit loss among veterans if they became employed. Ottomanelli et al. (2019) examined current practices, unique challenges, and future directions in VA VR services in polytrauma systems of care. They identified the following challenges, which will be used to frame the discussion here: (a) staffing, (b) benefits as a disincentive, (c) transitioning active-duty service members, (d) differing needs of a heterogenous population, (e) communication/collaboration, and (f) different employment data sources.

Regarding staffing, Ottomanelli et al. (2019) reported the VA needs more CWT staff to meet the needs of veterans with polytrauma. As a result, the VA may need to hire more VR counselors in near future to meet the needs of veterans with disabilities. Similar to Shepherd-Banigan et al. (2021)’s findings on concerns about benefit loss, Ottomanelli et al. (2019) reported that disability compensation may reduce motivation to seek employment if veterans and service members with disabilities are concerned about losing their financial and Social Security benefits. As such, rehabilitation professionals and benefits counselors may play a key role here to help veterans with disabilities understand their benefits.

In addition to staffing and concerns about benefits loss, many veterans and active-duty service members also need help regarding transition-related challenges. Specific VR programs serving a population of mostly active-duty service members may face unique issues due to transition-related factors (Ottomanelli et al., 2019). Therefore, VR services should have flexible approaches to provide the type and level of services appropriate for active-duty members. This service may help veterans and active-duty members with disabilities have a smooth transition from military life to civilian life.

Another significant challenge is that veterans are a heterogeneous population and, therefore, have different needs (Ottomanelli et al., 2019). Given veterans and service members may have different disabilities, co-morbidities, and clinical features, it is challenging to design and implement VR programs to meet the needs of these diverse veterans and service members. Although it may be challenging and costly, individualized rehabilitation and employment services for veterans and service members would be more helpful based on specific needs and challenges. It is also important for rehabilitation professionals, researchers, and policymakers to understand emerging needs and challenges. For example, because of advanced technology, more veterans are able to survive from severe injuries; however, these veterans may live with severe disabilities (e.g., polytrauma), which may be challenging for rehabilitation and employment process. Policymakers and health administrators may invest more in improving functioning and eventually community participation among Veterans with CID.

Finally, another significant challenge is different employment data sources. There are three separate sources (i.e., the VHA electronic medical record, the VA TBI Model System (VATBIMS) Program of Research database, and the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center) for information on employment of veterans with TBI, where some of the data is difficult to extract and analyze when needed. The authors reported that collaboration among those responsible for the data is important for improving research and informing program development that meets the vocational needs of veterans with TBI (Ottomanelli et al., 2019).

When it comes to barriers and challenges, it is also important to highlight service access difficulties among veterans living in rural areas. Many veterans live in rural areas (~4.7 million; 8% women; 10% minorities; Office of Rural Health, 2022). Rural veterans experience significant barriers, such as access to healthcare (particularly specialty care), limited internet access, greater fewer transportation options, higher uninsured rates, longer wait times, and hospital closures due to financial instability (Office of Rural Health, 2022). Rural veterans do not always live around a VA center. For example, the upper peninsula of Michigan is an isolated area, where rural veterans struggle to reach VA or non-VA care due to hospital closings, fewer housing, and transportation options, greater geographic and distance barriers, limited internet, and difficulty of safely aging. In addition, underserved rural veterans are often unaware of the benefits, services, and facilities available to them.

Opportunities to Improve Veterans’ Rehabilitation and Employment

Although there are many challenges and barriers in rehabilitation and employment services for veterans with disabilities, there are ways to improve rehabilitation and employment services for veterans with disabilities. This section will cover certain opportunities to improve VR services for veterans with disabilities.

Shepherd-Banigan et al. (2021) examined factors to improve VR services for veterans and reported that veteran motivation, caregiver and family support, and engaged VA and academic counselors were key factors in improving the use of VA vocational and educational services. According to their findings, an efficient VA application process and a proficient staff were important facilitators of VA vocational and educational service use. Veterans also believed VR specialists are important in helping them effectively use VA vocational and educational services. In addition, universities, faculty, and disability specialists play significant roles for veterans using educational benefits. Veterans reported that when academic institutions’ support them, there is an increase in their academic success, which may increase their employment outcomes.

As reported above, in their study of perceptions of state VR agency administrators on SVRA and VA VR&E Programs, Johnson et al. (2017) identified that co-service practices could improve employment outcomes among minority veterans with disabilities. Via survey methodology, researchers surveyed 39 SVRA administrators that were members of the Council of State Administrators of Vocational Rehabilitation (CSAVR) on whether they (a) currently engage in collaborations with VA VR&E Programs to serve minority veterans with disabilities or (b) had prior collaborations. Participants reported sometimes to usually collaborating with VA VR&E Programs to serve minority veterans with disabilities, both now and in the past. Participants were also asked to rate their current or prior involvement in 15 different co-service practices with the VA VR&E. Respondents indicated they were rarely involved in conflict resolution procedure development with VA VR&E, and sometimes too often involved in the referral procedure with VA VR&E. Participants were also asked to rate the effectiveness of 15 SVRA and VA VR&E co-service practices, irrespective of whether or not they engaged in these practices. Findings revealed slight-to-moderate effectiveness for the job training manual development, and moderate-to-high effectiveness for both the referral process development and the development of co-hierarchy and co-responsibilities. Among nine potential SVRA and VA VR&E co-service challenges, participants considered a lack of diversity as a slight-to-somewhat barrier and inconsistent collaborations as a somewhat-to-moderate barrier. Finally, participants were asked to rate identified positions within SVRAs that could be part of co-service practices with VA-VR&E Programs, reporting that all positions, including directors, program managers, field coordinators, rehabilitation counselors, job development specialist, and rehabilitation technicians, should be engaged (Johnson et al., 2017).

Better and more specific training of professionals working with veterans could improve their employment-related outcomes. Frain et al. (2010) reported that the rehabilitation counseling field should have further training and curriculum-related activities that introduce veterans, the rehabilitation needs of veterans, and the overall challenges that affect veterans with disabilities in their daily life. Rehabilitation counselors should be familiar with techniques to screen physical and mental illnesses among veterans, suggesting that the field of rehabilitation counseling should expand its curriculum and training materials to cover the needs of veterans with disabilities. Given VA statistics previously reported, unemployment and homelessness are significant issues among veterans, and can lead to veterans with disabilities facing significant employment-based needs. Rehabilitation counselors need to understand these specific employment-related needs among veterans (Frain et al., 2010). Rehabilitation professionals have the skills and knowledge related to employment reintegration, employer education, and transferable skills analysis to help veterans with disabilities to address their employment-related needs.

In another study, Frain and colleagues (2013) examined current knowledge and training needs of CRCs to work effectively with veterans with disabilities. Their results revealed that CRCs reported low levels of preparation in some of the areas deemed important by veterans and professionals. CRCs did not feel they were being sufficiently trained to work with veterans with disabilities. Given rehabilitation counseling curriculum has not been expanded substantially to work effectively with veterans with disabilities since 2013, rehabilitation counselors who are newly employed in state VR or VA VR services may not feel ready to work effectively with veterans with disabilities. Rehabilitation counseling programs should collaborate closely with VA VR services so that interested students may at least have practicum and internship experiences in these settings, which may increase their knowledge of veterans with disabilities.

Given disability is already common in veterans and negatively affects employment outcomes, secondary conditions could present further barriers in achieving optimal rehabilitation and health outcomes in veterans with disabilities. Therefore, rehabilitation counselors may aim to improve self-management behaviors in veterans with disabilities (Frain et al., 2010). To do that, rehabilitation counselors can easily screen self-management behaviors by using psychometrically sound scales with veterans with disabilities. Based on the screening results, rehabilitation counselors can provide psychoeducation to improve self-management behaviors in this population (Frain et al., 2010).

Families could play significant roles in the health and rehabilitation outcomes of veterans. In addition to focusing on veterans, it is also important that rehabilitation counselors focus on veterans’ families to address their holistic needs (Frain et al., 2010). Veterans’ family members may also be experiencing considerable difficulties, in which rehabilitation counselors can offer support by implementing coping skills and providing resources to them. Through the lens of a holistic rehabilitation and health service approach, rehabilitation counselors could facilitate the development of overall family resilience in veterans and their family members so they are better equipped to face daily challenges, stress and pressure (Frain et al., 2010).

Finally, research on the needs of veterans with disabilities is warranted in rehabilitation counseling (Frain et al., 2010). Recently, rehabilitation researchers have published and presented research findings on veterans’ health, postsecondary education outcomes, and overall life adjustment (e.g., Eagle et al., 2022; Umucu, 2021; Umucu, Brooks, et al., 2018; Umucu et al., 2020; Umucu, Grenawalt, et al., 2018; Umucu, Reyes, et al., 2021; Umucu, Villegas, et al., 2021). Positive psychology, a contemporary approach, was explored to determine whether positive psychology factors explain positive rehabilitation outcomes, including community participation, in veterans with and without disabilities. It is recommended that rehabilitation professionals incorporate positive psychology techniques and interventions into rehabilitation process. For example, grit was found to uniquely account for a significant proportion of variance in functional disability (Umucu, Villegas, et al., 2021); as such, rehabilitation clinicians may find ways to incorporate grit and other positive psychological constructs (e.g., resilience) into VR services. Collaborative and interdisciplinary research is needed in this area to further examine and understand the needs of veterans with disabilities.

Conclusion

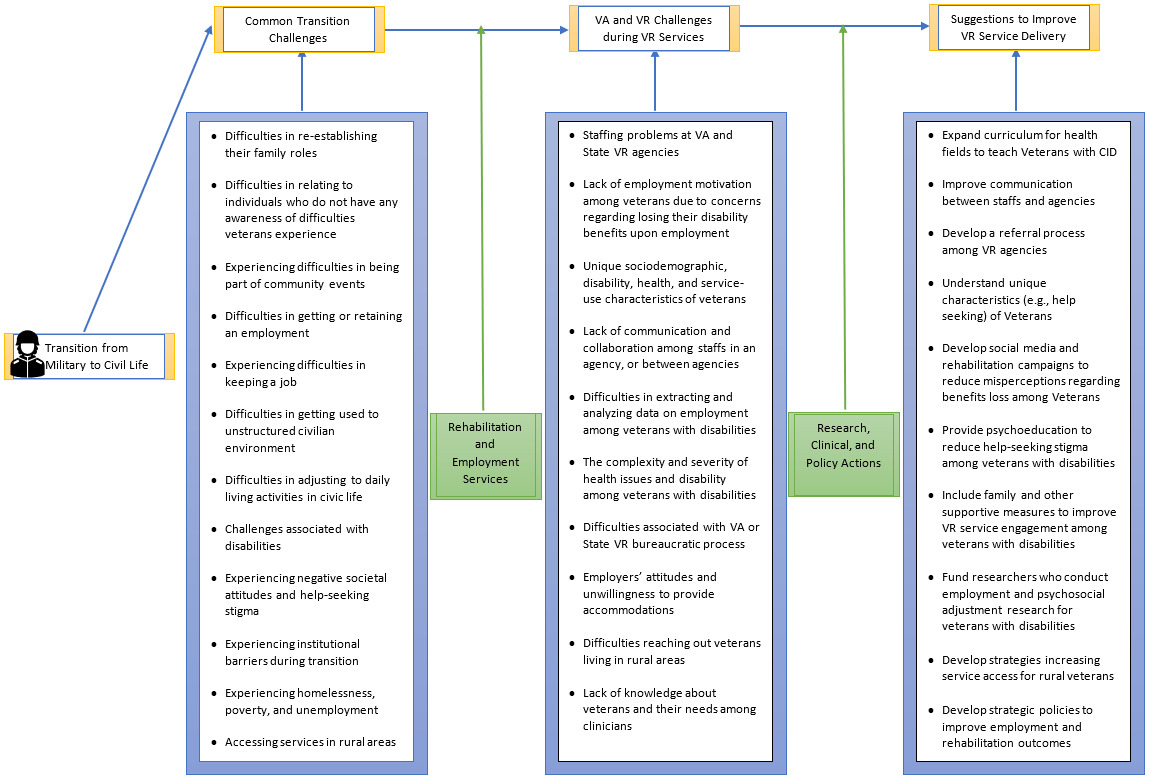

With this study, literature on the vocational rehabilitation needs of veterans with disabilities was synthesized. To summarize, Figure 1 represents a conceptualization of helping veterans with disabilities during VR process based on these findings. It is important that audiences understand that this literature review has certain limitations. The most important limitation is that this manuscript did not represent a complete systematic literature review. Instead, only certain studies were included to elucidate the strengths, challenges, and barriers of services to veterans with disabilities. Overall, the goal was to help rehabilitation and mental health service providers understand sociodemographic, disability, health, and service-use characteristics of veterans. Future efforts will include a systematic review of the literature to understand the scope of evidence-based practices, services, and factors leading to the most effective employment and wellness outcomes.

Author’s Note

The contents of this article summary were developed under a grant, the Vocational Rehabilitation Technical Assistance Center for Quality Employment, H264K200003, from the U.S. Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal government.