Job satisfaction is “a person’s overall evaluation of his or her job as favorable or unfavorable” (Meier & Spector, 2015, p. 1). The concept of job satisfaction tends to be highly studied because job satisfaction is an attitude that can influence thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of employees, and has been linked to various outcomes related to employees’ productivity and health. Concerning productivity, employees who like their job seem to perform better than employees who are not satisfied with their job (Fassina et al., 2008). In their meta-analysis, Tett and Meyer (1993) concluded that job satisfaction predicted intention to remain employed in the organization. In terms of health, Spector (1997) reported job satisfaction as inversely related to burnout, positively associated with mental and physical health, and positively associated with life satisfaction of employees. Overall, job satisfaction seems to be an important element of employee productivity and well-being.

Given the impact of job satisfaction on individuals and organizations, predictors of job satisfaction have also been widely studied. Meier and Spector (2015) described predictors of job satisfaction to fall within three categories: person, environment, and interaction between person and environment. First, person-based factors (e.g., personality) have been found to be associated with job satisfaction. Dimensions of personality such as openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness have been positively associated with job satisfaction (Bui, 2017; Perera et al., 2018). Self-esteem has been positively associated with job satisfaction (Alavi & Askaripur, 2003). People with an internal locus of control have also been noted to have higher levels of job satisfaction compared to people with external locus of control (Padmanabhan, 2021). Second, environmental factors seem to influence job satisfaction. In their study of professionals across age groups, Bos et al. (2009) found that positive relationships with colleagues and skill discretion (i.e., using wide range of skills) were positively associated with job satisfaction. Task significance (i.e., the extent to which tasks being performed impacts the organization) has also been positively associated with job satisfaction (Khalil & Sahibzahah, 2017). In their survey of recent college graduates, Lee and Sabharwal (2016) concluded that education-job match predicted job satisfaction in public, non-profit, and for-profit sectors. However, giving credence to the interaction between person and environment in that same study, increased salary can sometimes make up for lack of education-job match. Third, Meier and Spector (2015) posited that not every employee will be affected the same by personal and environmental characteristics because different people prefer different work conditions. For example, in their study Verquer et al. (2003) concluded that job satisfaction was highest when the difference between what people want in a job and what they are getting was smallest. Supervisor support has also been positively linked to job satisfaction (Ng & Sorensen, 2008). In reviewing the literature, it is clear that predicting job satisfaction is complex.

Specific to rehabilitation counselors, Herbert et al. (2020) found an association with job satisfaction and fit between person and organization values, and also identified that certain work personalities (e.g., artistic: promotes self-expression and prefers to avoid ordered and repetitive tasks, social: working directly with people) may be incompatible with state vocational rehabilitation, as it is currently structured. Zheng et al. (2017) found a positive relationship between job satisfaction and all six physical environmental factors (i.e., location, safety, health environment, facility space, comfort, professional nature) among a sample of rehabilitation professionals. Pitt et al. (2013), in their study of vocational rehabilitation counselors, stated that limitations with career promotions and supervision negatively affected job satisfaction and recommended improvements in those areas. Tabaj et al. (2015) studied job satisfaction in relation to work stress, burnout, and compassion and concluded that, as the period of employment increased, job satisfaction decreased and burnout increased. Further, increased work stress (caused by high work demands, time pressure, and too many administrative tasks) was negatively associated with job satisfaction. Tabaj et al. (2015) recommended offering counselors support to help reduce work stress. O’Sullivan and Bates (2014) concluded that workplace cultures that promote overall well-being have the potential to help reduce burnout and help counselors flourish. Multiple factors seem to influence job satisfaction among rehabilitation counselors.

Based on the review of the literature, various person and environmental factors predict job satisfaction, including in rehabilitation counseling. One factor that has not been thoroughly investigated in relation to job satisfaction of rehabilitation counselors is prosocial behaviors in the workplace. Prosocial behaviors cover “a broad range of actions intended to benefit one or more people other than oneself” (Batson & Powell, 2003, p. 463). Examples of prosocial behaviors include sharing resources or comforting someone in distress—all with the intention of helping people. Within organizations, prosocial behaviors are (a) performed by a member of an organization, (b) directed toward an individual, group or organization in which they interact while carrying out their organizational role, and (c) performed with the intention of promoting the welfare of the individual, group or organization toward which it is directed (Brief & Motowidlo, 1986). Katz (1964) pointed out that prosocial behaviors can be role-prescribed behaviors (i.e., required by the job) or extra-role behaviors (i.e., not explicitly assigned). Rehabilitation counselors are in a helping profession and carry out prosocial behaviors routinely as part of their job requirements (e.g., cooperating with clients, sharing information with clients, comforting clients in distress) and these would be considered role-prescribed prosocial behaviors. An example of an extra-role prosocial behavior could be a rehabilitation counselor volunteering to provide information to a new counselor with the intention to help the new counselor be successful with a demanding case. Another example of an extra-role prosocial behavior could be for a counselor to listen to a fellow counselor about a concern they are having and show empathy and warmth to their co-worker. Prosocial behaviors occur within and outside of organizations, can be prescribed or extra-role behaviors, and are a form of support at work for recipients.

Prosocial behaviors have been linked to benefits for individuals and organizations. In their meta-analysis, Podsakoff et al. (2009) concluded that organizational citizenship behaviors, such as prosocial behaviors, are inversely linked to employee turnover intention, actual employee turnover, and absenteeism. Additionally, employees who act in prosocial ways seem to have more positive affect towards their job, but also perceived those prosocial behaviors influenced their work productivity (Koopman et al., 2016). In the same meta-analysis, which included some longitudinal studies, Podsakoff et al. (2009) identified several organizational-level outcomes that seem to be related to organizational citizenship behaviors, including productivity, customer satisfaction, and efficiency. It appears that organizations benefit from prosocial behaviors in the workplace. Much work has also been done regarding the motivation for prosocial behavior in organizations to help explain why someone would or would not engage in prosocial behaviors at the workplace and leadership seems to be a key factor (see also Bolino & Grant, 2016). Employees are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors, such as sharing information and advocating for others, when they have supervisors who are trusted and supportive (Detert & Burris, 2007; Podsakoff et al., 2009). Prosocial behaviors can be provided by various individuals in the workplace including co-workers and supervisors, and multiple factors influence the motivation for and consequences of providing and receiving prosocial behaviors in the workplace.

While prosocial behaviors can be provided by any individual in an organization, some literature has investigated the role of supervisors and leaders regarding prosocial behaviors and supports in organizations. Counselors who have leaders (supervisors and managers) that display high levels of support tend to have higher levels of job satisfaction compared to those counselors who perceive to have leaders displaying lower levels of support (Packard & Kauppi, 1999). Packard and Kauppi (1999) concluded that rehabilitation counselors in their study preferred relationship-oriented leaders who took an active interest in supporting counselors. Interpersonal relationships with supervisors were found to be positively associated with job satisfaction, with higher job satisfaction associated with higher ratings of interpersonal relationships (Garske, 2000). Literature has stated the importance of moving the rehabilitation counseling supervision process to include a focus on support and development of counselors’ skills and professional development, instead of only focusing on administrative and compliance-based supervision (Schultz, 2008). However, barriers to supportive supervision seem to be present in the field (Herbert et al., 2020). Sabella et al. (2020) call for counselor evaluation procedures that work toward supporting counselor professional development. The role of supervisor is to provide administrative oversite, offer clinical supervision and facilitate professional development for counselors (Schultz, 2008), and these functions cannot be replaced by others in the organization. During supervision, however, it appears many counselors experience times they are not receiving support from their supervisors. Therefore, while others in the organization cannot provide clinical supervision and administrative support, perhaps others in the organization can provide other types of support.

Given the connection between supportive, prosocial behaviors and job satisfaction, as well as the barriers experienced by many rehabilitation counselors regarding support from supervisors, it is helpful to explore other sources of support rehabilitation counselors may use to maintain job satisfaction. While non-supervisors cannot replace the important supervisor functions of administrative oversite, clinical supervision, and professional development of counselors, it may be possible that others/non-supervisors in the organization can provide prosocial behaviors and support that can improve the rehabilitation counselor’s job satisfaction. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore job satisfaction and receiving prosocial behaviors among a sample of rehabilitation counselors. The specific research questions for the current study are:

- To what extent are rehabilitation counselors receiving prosocial behaviors within their organization?

- Which prosocial behaviors are most strongly associated with job satisfaction?

- Does receiving prosocial behaviors and perceived supervisor support interactively predict job satisfaction?

Method

Participants

Within the study, 805 participants visited the survey link. We included participants who, at the time they completed the survey, were (a) rehabilitation counselors, (b) currently employed in the public sector vocational rehabilitation system, (c) currently working with clients, and (d) were not missing any responses to the scales used in the analyses. After excluding participants who did not meet these criteria, we had a final sample of 581 rehabilitation counselors.

In the final sample, the mean age of counselors was 45.25 years (SD = 12.42), 79.7% identified as female (19.3% male, less than 1% other), and 67.1% identifying as non-Hispanic White (12.0% Black/African American). Regarding education and credentials, 90.2% reported holding at least a master’s degree, 56.1% reported graduation from a rehabilitation counseling master’s program, and 43.4% reported currently holding the Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC) credential. Counselors reported an average of 10.20 years (SD = 8.50) of work experience in public vocational rehabilitation and an average current caseload of 100.74 (SD = 44.20) clients. Counselors reported meeting with an average of 24.10 (SD =15.45) clients per week either in-person, by phone, or online, and reported an average of 23.11 (SD = 10.75) client contact hours per week. Finally, counselors reported the severity of their clients limitations: 51.5% reported most of their clients were severe (limitations in three or more areas of functioning), 45.1% reported most of their clients were moderate (limitations in two areas of functioning), and 3.4% reported most of their clients were mild (limitations in one area of functioning).

Procedures

Upon Institutional Review Board approval, we worked with the Council for State Administrators of Vocational Rehabilitation (CSAVR) to recruit participants. CSAVR asked their state directors to send a recruitment email to rehabilitation counselors employed in their state. The email contained a brief description of the study and a link to the online survey. To minimize any perceived pressure to participate, the recruitment email emphasized that participation was voluntary and all responses were anonymous (i.e., their state directors and supervisors would not know who participated or not, nor would their state directors and supervisors have any access to individual responses). After agreeing to participate, participants completed the online survey (described in the section below). Once they completed the survey, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Instrument

First, participants reported whether they were currently employed as a rehabilitation counselor in the public vocational rehabilitation system. Next, counselors responded to two items about their intention to stay in their current position and the Mobley Turnover Intention Scale (Mobley, 1977; Mobley et al., 1978). Participants then reported how much they wanted to receive and how much they actually received each of 12 supervision activities. These scales are not relevant to the current research questions and are not discussed further.

Participants then completed the Perceived Supervisor Support Scale (Eisenberger et al., 1986). This 5-item scale measures participants’ perception that they have a positive and supportive relationship with their supervisor. Participants responded to these items on scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example items are “my supervisor holds me in high regards” and “my supervisor values my contributions.”

Participants then reported the extent to which they received 17 prosocial behaviors. These behaviors were adapted from items on a Mentoring Scale (Dreher & Ash, 1990). Whereas previous research has asked participants to report how much they received these prosocial behaviors from their supervisor, participants in the current study reported how much they received these prosocial behaviors from “someone from [their] current organization.” This change in wording means that responses indicate whether a particular counselor received these behaviors at all and not only whether they received these behaviors specifically from their supervisor. Participants responded to these items on scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very large extent). Example items are whether somebody in their current organization “conveyed feelings of respect for you as an individual,” “helped you finish assignments/tasks or meet deadlines that otherwise would have been difficult to complete,” and “encouraged you to prepare for advancement.”

Participants then completed the Job Satisfaction Scale (Macdonald & Maclntyre, 1997). This 10-item scale measures the extent to which participants were satisfied with their current job. Participants responded to these items on scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items are “I feel good about working at this organization,” “I feel secure about my job,” and “all my talents and skills are used at work.”

Finally, participants reported their caseload size, the amount of weekly contact hours they have with clients, the functioning level of their clients, age, gender, ethnicity, education, the number of years of service they had in state vocational rehabilitation and rehabilitation counseling, and their certification status.

Data Analysis

Research Question 1 is a simple descriptive research question answered by computing the average of participants’ self-reported receiving of each prosocial behavior. Research Question 2 involves the relationships between receiving individual prosocial behaviors and job satisfaction; thus, this research question was answered with a series of bivariate correlations between each prosocial behavior and counselors’ job satisfaction. Finally, Research Question 3 involved the relationship between how much counselors generally received prosocial behaviors, their perceived supervisor support, and their job satisfaction. Thus, Research Question 3 was answered with a multiple regression analysis where the total amount of prosocial behaviors received (i.e., the average of all the individual prosocial behavior items), perceived supervisor support, and an interaction term predicted counselors’ job satisfaction.

Results

Research Question 1: To What Extent Are Rehabilitation Counselors Receiving Prosocial Behaviors Within Their Organization?

Counselors reported the extent to which “someone from your current organization” engaged in several helping behaviors. Responses were made on 5-point scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very large extent). As can be seen in Table 1, counselors reported, on average, receiving a moderate amount of prosocial behaviors. The prosocial behavior with the lowest average was 2.08 (SD = 1.25) for the item “protected you from working with other managers or work units before you know about their likes/dislikes, opinions on controversial topics, and the nature of the political environment.” The prosocial behavior with the highest average was 3.31 (SD = 1.34) for the item “conveyed feelings of respect for you as an individual.”

Research Question 2: Which Prosocial Behaviors Are Most Strongly Associated With Job Satisfaction?

Counselors’ job satisfaction was computed by taking the average of the 10 items of the Job Satisfaction Scale (α = .87). Counselors’ job satisfaction ranged from 1 to 5, with an average of 3.30 (SD = 0.83). Each prosocial behavior was significantly and positively correlated with job satisfaction (all p’s < .001). The magnitude of the correlations ranged from r = .31 to r = .59. Thus, all the correlations between the prosocial behaviors and job satisfaction are in the range that is conventionally considered medium to large (Cohen, 2013). The item with the weakest association with job satisfaction was “protected you from working with other managers or work units before you know about their likes/dislikes, opinions on controversial topics, and the nature of the political environment.” The two individual prosocial behavior items with the strongest association with job satisfaction were “displayed attitudes and values similar to your own” (r = .59) and “conveyed feelings of respect for you as an individual” (r = .59).

Research Question 3: Does Receiving Prosocial Behaviors and Perceived Supervisor Support Interactively Predict Job Satisfaction?

For the next analyses, we computed an aggregate scale of how much counselors received prosocial behaviors. This aggregate scale is the average of the items for the 17 individual prosocial behaviors (α = .95). The frequency of prosocial behaviors counselors reported receiving ranged from 1 to 4, with an average of 2.70 (SD = 0.97). We also computed counselor’ perceived supervisor support by averaging together the five items of the Perceived Supervisor Support scale (α = .98). Counselors’ perceived supervisor support ranged from 1 to 7, with an average of 4.90 (SD = 1.92).

Counselors’ job satisfaction, prosocial behaviors received, and perceived supervisor support were all significantly correlated: job satisfaction and prosocial behaviors, r(579) = .62, p < .001; job satisfaction and perceived supervisor support, r(579) = .48, p < .001; and prosocial behaviors and perceived supervisor support, r(579) = .42, p < .001.

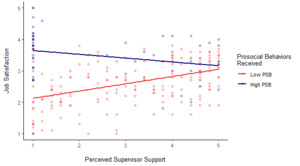

A linear regression analysis predicted counselors’ job satisfaction from the (mean-centered) amount of prosocial behaviors they received, their (mean-centered) perceived supervisor support, and the (mean-centered) Prosocial Behavior × (mean-centered) Perceived Supervisor Support interaction. The overall model was statistically significant, F (3, 577) = 161.20, p < .001. There were significant main effects for the amount of prosocial behaviors received, b = 0.41 (SE = 0.03), p < .001, and for perceived supervisor support, b = 0.12 (SE = 0.01), p < .001. As prosocial behaviors and perceived supervisor support increased, counselors reported higher job satisfaction. However, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction, b = -0.05 (SE = 0.01), p < .001 (see Figure 1).

To interpret this significant interaction, we examined the relationship between perceived supervisor support and job satisfaction for counselors who received different amounts of prosocial behaviors. We first recoded the amount of prosocial behaviors received such that a score of zero corresponded to “not at all,” which was the minimum value on the prosocial behavior scale (i.e., this new predictor was computed by subtracting 1 from the prosocial behaviors total score), and reran the model specified above. For counselors who received the minimum level of prosocial behaviors, the relationship between perceived supervisor support and job satisfaction was relatively strong, b = 0.20 (SE = 0.03), p < .001. Specifically for counselors who received the minimum level of prosocial behaviors, a one-unit increase in perceived supervisor support was associated with an increase of 0.20 points on the Job Satisfaction Scale.

Next, in a separate analysis, we recoded the amount of prosocial behaviors received such that a score of zero corresponded to “to a very large extent,” which was the maximum value on the prosocial behavior scale (i.e., this new predictor was computed by subtracting 5 from the prosocial behaviors total score), and reran the model specified above. For counselors who received the maximum level of prosocial behaviors, the relationship between perceived supervisor support and job satisfaction became essentially zero, b = 0.02 (SE = 0.03), p = .60.

In all, job satisfaction is higher among counselors who are receiving more prosocial behaviors, have higher perceived supervisor support, or both. Conversely, job satisfaction is lowest for counselors who are not receiving many prosocial behaviors and who have lower perceived supervisor support. Importantly though, receiving prosocial behaviors and perceived supervisor support seem to compensate for one another: Receiving few prosocial behaviors does not lead to lower job satisfaction if the counselor perceives they have high supervisor support and vice versa.

Discussion

In the current study, rehabilitation counselors reported the extent to which they received prosocial behaviors at their organization, how supportive they perceive their supervisor, and their job satisfaction. From these data, we tested whether prosocial behaviors received and perceived supervisor support predicted counselors’ job satisfaction.

Regarding Research Question 1, we found that rehabilitation counselors received, on average, a moderate amount of prosocial behaviors from individuals in their organization. Many of the most highly reported prosocial behaviors—which were items such as “conveyed feelings of respect for you as an individual” and “conveyed empathy for the concerns you have discussed with them”—were about counselors’ feelings that other people in their organization were showing interpersonal warmth and respect. Other highly reported prosocial behaviors—which were items such as “given challenging opportunity to learn new skills,” “shared history of their career with you,” and “served as a role model”—were about counselors’ feelings that others were trying to help with their professional development. Hearteningly, on average, all of the prosocial behaviors were reported to be received a moderate amount. We considered that this finding on the mid-point of the scale might be due to a bimodal distribution (e.g., most individual counselors reported either receiving high levels of prosocial behaviors or very few prosocial behaviors, which, when averaged together, would result in averages near the mid-point of the scale). However, none of the prosocial behaviors had bimodal distributions.

Given that prosocial behaviors have not been previously investigated in the rehabilitation counseling literature, it is not possible to say how this result compares to previous studies of rehabilitation counselors. However, the amounts of prosocial behaviors received in the current study were comparable to previous studies of working populations outside of the counseling professions (Dreher & Ash, 1990). Therefore, prosocial behaviors are being received by rehabilitation counselors in the sample, but not at extreme amounts (high or low).

Regarding Research Question 2, receiving more prosocial behaviors was associated with higher job satisfaction. This finding supports Garske’s (2000), that low levels of interpersonal relations with supervisors tend to be associated with lower levels of job satisfaction, and is also consistent with Alavi and Askaripur’s (2003) finding that job satisfaction is related to satisfaction with co-workers. It is also important to note that when rehabilitation counselors in this study were asked about their experiences receiving prosocial behaviors, they were asked how frequently they receive prosocial behaviors from an individual in the organization. Therefore, the prosocial behaviors could be from co-workers and/or supervisors. Nevertheless, this finding indicates that receiving support seems to be important in terms of job satisfaction for rehabilitation counselors in the study, regardless of the source within the organization.

Further, we found that all prosocial behaviors were significantly and positively associated with job satisfaction. This finding is consistent with previous research outside of the counseling profession, establishing the connection between supportive work environment and job satisfaction (Bos et al., 2009). The results of this study also extend the literature regarding support in the workplace by showing that the prosocial behaviors most strongly associated with job satisfaction are those of an interpersonal nature showing empathy, warmth, and respect. Specifically, in the current study, the prosocial behaviors with the strongest associations with job satisfaction were receiving respect as an individual, empathy for the concerns discussed, attitudes and values that match the receiver, role modeling, and willingness to discuss concerns. It is possible that the rehabilitation counselors in this study received some of these prosocial behaviors from supervisors, which would emphasize the critical nature of the supervisor working alliance in relation to job satisfaction (Bordin, 1983). Again, the supervisor’s role must include administrative oversight, clinical supervision, and professional development, but be grounded in a positive working relationship (Schultz et al., 2002). In this study, some of these prosocial behaviors may have been received from others in the organization, besides a supervisor. This suggests that positive interpersonal relationships with peers also contribute to job satisfaction. So, regardless of where the prosocial behaviors originate (i.e., someone in the organization), receiving prosocial behaviors of an interpersonal or relationship focus, including empathy and warmth, seem to be helpful in predicting job satisfaction among rehabilitation counselors. Future research could examine whether who gives the prosocial behavior is a meaningful moderator of how those behaviors affect job satisfaction.

Research Question 3 examined whether prosocial behaviors make up for lack of perceived supervisor support in relation to job satisfaction. This seemed to be the case. Prosocial behaviors and perceived supervisor support are both related to job satisfaction; however, prosocial behaviors and supervisor support compensated for one another in terms of job satisfaction. Therefore, counselors are not doomed, in terms of job satisfaction, if they are not receiving support from their supervisor, if they are receiving prosocial behaviors from others in the organization. Alternatively, it seems like counselors in the study who were not receiving prosocial behaviors from others in the organization but reported receiving high levels of support from their supervisor also had high levels of job satisfaction.

The role of the supervisor in an organization is critical for helping counselors establish and maintain clinical skills, providing necessary administrative accountability, and providing counselors with professional development. While no one can replace the important functions of a supervisor, receiving prosocial behaviors from individuals in an organization may be able to offset the impact on job satisfaction for times when low levels of supervisor support occur. This is important because the ebb and flow of organization budget cuts, staffing shortages, clients with many needs, and sociopolitical issues can influence the day-to-day experience of a counselor in terms of a supervisor’s ability to provide support. Supervisors wear many hats and sometimes are even carrying their own client caseload in addition to supervising a team of counselors. While one would hope that persistent barriers to supportive supervision are addressed, at any given time, organizations may be in periods of transition or crisis that can affect the level of support a counselor can receive from their supervisor. The current study is important in pointing out that during those periods, prosocial behaviors may be able to help. Counselors are encouraged to seek prosocial behaviors from individuals in their organization.

Limitations, Caveats, and Future Directions

The outcome variable in this study is job satisfaction. Although receiving prosocial behaviors seemed to compensate for lack of supervisor support in relation to job satisfaction, there are likely other outcomes not measured in this study that can be damaged by lack of supervisor support, for which prosocial behaviors cannot compensate. Future research could investigate additional outcomes, besides job satisfaction, during low rates of supervisor support.

Another major limitation of this study is that it is cross-sectional. While we can say that job satisfaction and prosocial behaviors are positively correlated, this design makes it impossible to draw any conclusion if prosocial behaviors cause job satisfaction. Future research could use the proper methods to test whether, for example, increases in prosocial behaviors cause increases in job satisfaction and other meaningful outcomes.

Finally, it is important to consider that the sample only included state vocational rehabilitation employees. As with any setting, state vocational rehabilitation has distinctive policies, procedures, and organizational culture. It is possible that the results of this study could be relevant only to the state vocational rehabilitation counselor population and might not be representative of all rehabilitation counselors.

Conclusion

Job satisfaction affects employees’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Fostering a culture that facilitates high job satisfaction can result in positive impacts on individuals and organizations. The current study showed that receiving prosocial behaviors is positively related to job satisfaction among rehabilitation counselors in state vocational rehabilitation counseling agencies. The current study also demonstrated that prosocial behaviors could compensate for, in terms of job satisfaction, low levels of support from supervisors. While the important functions of a supervisor cannot be replaced, it is helpful to understand how receiving prosocial support from any individual in the organization is positively associated with job satisfaction. To maintain job satisfaction, counselors need support from their organization and this study showed that counselors could receive that support from various sources. Most importantly, counselors that are not experiencing high levels of perceived support from their supervisor are not doomed to experience low levels of job satisfaction forever. Instead, counselors can feel empowered to reach out to others in the institution to get support and perhaps improve job satisfaction.