Centers for independent living (CILs) and state vocational rehabilitation (VR) agencies have opportunities to collaborate on joint service provision for transition-age youth with disabilities. Additionally, in light of extant racial and ethnic disparities in services and transition outcomes among youth with disabilities (McFarland et al., 2016; Shogren & Shaw, 2017; Thoma et al., 2016), such collaborations could be a powerful tool in mitigating such inequities. VR agencies offer services related to helping people with disabilities obtain or maintain employment, including services to support youth transitioning from school to adulthood. CILs operate in communities to offer a range of independent living services to individuals with disabilities and their families. Transition-age youth with disabilities can benefit from the valuable and complimentary services of CILs and VR agencies. Collaborations between CILs and VR agencies might be particularly important to support the transitions of youth with disabilities from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, who often disproportionately face additional barriers. VR agencies and CILs can play complementary roles in supporting transitions, and coordination between the two can ensure that resources are leveraged effectively to meet youth’s needs.

This study employs publicly available data from the Rehabilitation Services Administration’s Case Service Reports (RSA-911) for all VR agencies to examine the relationships between CILs and VR agencies at the national and state levels regarding transition-age youth (youth and young adults ages 14 to 24). We focus on two types of collaborations: referrals from CILs to VR agencies, and VR youth’s use of CIL services that are comparable to those from the VR agency. The RSA-911 records document the referrals that VR agencies receive from CILs, including youth characteristics and the types of VR services they used. They also contain information on some of the services VR youth use from CILs, though the data are incomplete. As such, this source provides a partial view of the collaborations between CILs and VR agencies on their joint work for transition-age youth with disabilities. This study is part of a broader research project funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) to promote the outcomes of transition-age youth with disabilities from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds who use CIL services. The project’s other activities include surveying CILs on practices, and pilot testing services that encourage recruitment of and service delivery for this population.

Transition Outcomes of Youth with Disabilities

Youth with disabilities have poorer employment and education outcomes than their peers without disabilities, on average. Among young adults (those ages 18 to 24) with disabilities in the U.S. in 2019, 76% had acquired a high school diploma, 27% had enrolled in college, and 27% worked (Cheng & Shaewitz, 2021). For young adults without disabilities, these rates were 88%, 43%, and 43%, respectively. These gaps in education can limit later earnings into adulthood (McFarland et al., 2017). For example, people who achieve certain milestones before age 30—high school completion, working full-time for a year, or marriage—are more likely to avoid poverty after age 30 (Inanc et al., 2021). Thus, youth with disabilities who encounter challenges in their education attainment and employment opportunities early on may face a lifetime of decreased earnings, increased poverty, and dependence on benefits.

Youth who are neither working nor in school represent 6% of the U.S. population ages 16 to 24 (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2015, 2020). This group of disconnected youth is disproportionately female and from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, has lower levels of educational attainment and higher rates of poverty, and has parents with lower employment rates and educational attainment. About one-third of disconnected youth reported not working because of a disability, many of whom received Supplemental Security Income or Medicare.

Role of CILs in the Transition Process of Youth with Disabilities

To empower people with disabilities to live independently, over 400 community-based CILs offer a variety of programs to promote independent living (National Council on Independent Living, n.d.). A key attribute of CILs is their consumer focus: people with disabilities lead and direct the centers. At the federal level, the Administration for Community Living (ACL) oversees CILs and provided over $90 million in total awards to 284 CILs in 2019 (Administration for Community Living [ACL], 2020). Not all CILs receive federal funding; some rely on state funding only. In addition to federal or state funding, CILs can obtain funding from other sources, such as through reimbursements from VR agencies for services provision. In 2020, about 236,000 people used services through federally funded CILs, of whom 20,000 were ages 5 to 19 and 14,000 were ages 20 to 24 (ACL, 2023). In addition, of the 351 federally funded CILs, 308 reported at least one youth using youth transition services in 2020 (ACL, 2023).

To receive federal funding, CILs must offer five core services, though they may offer additional ones. The core services include (1) information and referral, (2) independent living skills training, (3) peer counseling, (4) individual and system advocacy, and (5) services that promote transition to the community from institutions, assist those at risk of entering institutions, and encourage youth’s transition to adulthood (ACL, 2022). The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014 (WIOA) added the latter item to the centers’ required services. For the services involving youth transition, WIOA specifies a unique population: youth with significant disabilities who received secondary school services under an individual education program and completed or otherwise had left school. In addition to these required services, CILs may offer other services such as counseling, therapy, and personal assistance.

As required by WIOA, CILs offer youth-specific services to youth with significant disabilities to address the transition to adulthood after they leave secondary schools. In a 2020 survey of federally funded CILs, all offered services to this population (Harrison et al., 2022). Though WIOA emphasized one specific group of youth with disabilities, youth were a focus of CILs before WIOA, with self-determination activities cited as a key avenue for CILs to offer services to youth (Weymeyer & Gragoudas, 2004). CILs’ services to the broader youth population include goal setting, skill-building training for independent living, self-advocacy, information and assistance, and referrals for transportation.

Despite CIL staff members’ awareness of the need to prioritize offering services to youth, few CILs engage in partnerships with local education agencies or broader state-level collaborations around transition (Plotner et al., 2017). CILs can fill gaps in the transition service environment by contributing independent living and other peer-specific services (including community connections) that other transition providers, such as secondary schools and VR agencies, do not offer (Hammond et al., 2018).

Role of VR Agencies in the Transition Process for Youth with Disabilities

VR agencies offer employment-related services to people with disabilities under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These services assist people to “prepare for and engage in competitive integrated employment consistent with their unique strengths, priorities, concerns, abilities, capabilities, interests, and informed choice” (RSA, 2020, p. 5). Each state, along with the District of Columbia and the U.S. territories, has at least one agency, and some have two. Those with two agencies have one agency that offers services only to people who are blind or visually impaired and another that offers services to all other people with disabilities. The Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) oversees the funding for each VR agency, sets policies, and monitors agency outcomes. Most funding for VR agencies comes from the federal government (79%), with the remainder provided by states (RSA, 2020).

Services for youth with disabilities have become a higher focus for VR agencies in recent years. Though VR agencies have typically served this population, VR agencies began offering pre-employment transition services because of WIOA to all students with disabilities, including potentially eligible students with disabilities (those enrolled in secondary or postsecondary education institutions) before those students applied for services. WIOA requires at least 15% of an agency’s federal funding be allocated to these services (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2018). WIOA also emphasized VR agencies’ place in the state workforce system and increased their focus on collaborations with state and local organizations, including secondary education institutions. Among people who applied to, were determined eligible for, and received VR services under an individualized plan for employment (IPE), the proportion who were transition-age youth (those who were age 14 to 24) increased from about one-third of VR agencies’ caseloads before WIOA to about half after WIOA. Furthermore, additional youth used pre-employment transition services as potentially eligible students (RSA, 2020). In program year (PY) 2020, over 811,000 people had an IPE and used VR services, of whom around 419,000 were under age 25 (RSA, 2021).

Though all VR agencies offer the same broad set of services, their populations, policies, and outcomes vary (Taylor et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2021). These differences present opportunities to learn which types of agencies have more (or less) of a specific practice or outcome, and to identify opportunities to introduce or build up such practices.

Potential for CIL–VR Agency Collaborations in the Transition Process

Though WIOA made significant changes in the transition policy and practices for both CILs and VR agencies, the Act also emphasized increased collaboration among organizations more broadly. Both institutions might benefit from increased collaborations at the state and local levels to promote and coordinate services for transition-age youth, and potentially address the challenges that they and their families face with transition. CILs, for example, could refer youth using their services to VR agencies for accessing employment services, thereby furthering the youth’s postsecondary success. VR agencies, in turn, could refer youth to or contract for independent living services from CILs. Relevant CIL services can include goal setting, self-advocacy, partnering with families, and connecting youth with various providers and organizations to support their independent living goals (Plotner et al., 2017). VR and CIL services can play complementary and reinforcing roles: stable, paid employment can facilitate independent living and, at the same time, CIL services such as peer counseling and individual and systems advocacy can help youth obtain and maintain employment.

Interagency collaborations or partnerships are a best practice for VR agencies in general (Boeltzig-Brown et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2013) and for transition-age youth specifically (Awsumb et al., 2020). Though interagency collaborations around youth transition often focus on relationships with secondary education institutions, a review of a sample of 10 WIOA State Plans suggested that VR agencies can and do coordinate with CILs on youth services (Taylor et al., 2021). Such relationships might be particularly important for youth who are no longer in school, a group for whom school-based collaborations would not establish meaningful supports and services.

Research Questions

This study explores the potential for CIL and VR agency collaborations in providing services to transition-age youth, focusing on two types of collaboration: (a) referrals of transition-age youth from CILs to VR agencies and (b) CIL service use among transition-age youth who apply for VR services. We examined the following four research questions:

-

How common are collaborations between CILs and VR agencies?

-

What are the referral patterns from CILs to VR agencies for transition-age youth with disabilities?

-

What are the characteristics of transition-age youth referred by CILs to VR agencies, and what VR services did they use?

-

To what extent do VR youth use CIL services, and what are the characteristics of youth who do so?

Methods

Data and Sample

From RSA, we obtained a public use file of the annual RSA-911 case service report for PY2019. The RSA-911 records contain detailed information on individuals’ characteristics at the time of their VR application and (for those with an IPE) service use during the program year. The records contain information for everyone who applied for VR services, used VR services, or exited from VR during the program year, as well as some persons who exited before the program year but for whom the VR agency continued to report outcomes after exit. Our data included 77 VR agencies, which cover all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories of Guam, the Northern Marianas Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

We restricted the sample in two ways. First, we focused on transition-age youth (interchangeably referred to as youth throughout), or people who were ages 14 to 24 at the time they applied to the VR agency. Second, we excluded youth who had never applied for VR services. This restriction resulted in excluding youth who only used pre-employment transition services as students and did not apply to VR. We imposed this restriction because administrative records on non-applicants lack key information that is usually collected during the application (such as sex, impairment type, employment status at application, and referral source), which we needed for our analyses of CIL–VR collaborations. Additionally, the files RSA shares with researchers do not contain dates of birth, so we did not have access to the ages of students in this group. Because our sample is limited to youth who applied to VR and excludes non-applications, our findings might not generalize to all transition-age youth who use VR services. This criterion also resulted in our retaining youth who had applied but had not yet received services or who exited from the VR agency before obtaining an IPE in PY2019. These restrictions resulted in a sample of 570,781 youth who either applied for VR or used VR services during PY2019 (whether or not they exited during PY2019). We refer to this group as “VR youth.” Though these data may be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, we found similar results in the PY2017 and PY2018 data.

Measures

Our analysis examined the following four types of measures from the RSA-911 records:

Characteristics at Application

When people apply for VR services, they provide information on their sex, age, race and ethnicity, impairment type, education, living arrangements, primary source of financial support, employment status (at the time they create their IPE), barriers to employment, and whether they are a student with a disability.

CIL Referrals

VR agency staff collect information about the individual, agency, or other entity that referred the applicant to the VR agency, of which CILs are one possible source. Referral source is missing for 2,560 of the more than 500,000 youth in our analysis sample.

Types of VR Services Used

VR agencies offer various services related to a person’s employment goals as identified in their IPE. The RSA-911 records identify which services a person used during the program year. We assessed four types of commonly used services: pre-employment transition services, employment services, training services, and other services. Pre-employment transition services, which can only be used by students with disabilities, include counseling on enrollment opportunities, instruction in self-advocacy, job exploration counseling, work-based learning experiences, and workplace readiness training. These services can also be used by students before they apply for VR services. We document employment or career services as job placement, job search assistance, short-term job supports, supported employment, and all other career services. The five training services include any college (a combination of junior or community, four-year, and graduate college or university training), disability-related skills, job readiness, on-the-job, and all other training services. Finally, we examined other services, which covers any other services VR agencies offer, such as assessment, benefits counseling, diagnosis and treatment of impairments, maintenance, transportation, rehabilitation technology, VR counseling and guidance, and other services not otherwise captured in the above categories.

CIL Service Use

The RSA-911 records contain additional information on the service provider. People can use VR services in one of three ways: (a) directly from VR agency staff; (b) from a provider, with services purchased by the VR agency on behalf of the person; or (c) from a “comparable services and benefits provider,” with services paid for by that provider. The RSA-911 records identify comparable services and benefits providers for services from another public or private agency, institution, or provider not paid for by the VR agency. VR agency staff can list up to three provider codes for each service; “Public CIL” is one of 23 possible codes. We identify CIL service use based on the use of the Public CIL code for a comparable services and benefits providers.

A key limitation of the RSA-911 records—and therefore our measures of CIL service use—is that they do not enable us to identify a CIL as a provider of purchased services. For purchased services, the RSA-911 records have four codes to identify the type of provider from which services were purchased: public community rehabilitation program, private community rehabilitation program, public service provider, and other private service provider. VR agencies may have contracted with CILs to provide specific services to a person through a purchasing arrangement, but the data do not contain sufficient detail to identify a CIL as a provider of purchased services. Thus, our measures of CIL service use may underestimate the services that people use from CILs under an IPE because they can only capture services that are used from CILs as comparable services and benefits providers.

Another limitation is that we only observe services that fall under the VR agency’s domain, which is a limited set of services that pertain to employment goals. CILs offer many services, only some of which relate to employment. Many CIL services (for example, psychological counseling, self-advocacy, and peer support) cannot be captured in the RSA-911 data. Thus, our analysis may overlook some services youth use from CILs that do not fall under the domain of the VR agency.

Analysis Methods

We rely largely on descriptive statistics for the population of VR youth (ages 14 to 24) and adults (ages 25 and higher) in PY2019. These statistics include the number, percentage, and mean for CIL referrals, CIL service use as a provider of comparable services and benefits, the types of VR services used, and individual characteristics at application for various youth.

We calculated statistics on CIL referrals and VR service use at both the national and state VR agency levels. We calculated the number and share of VR agencies’ CIL referrals, and we also assessed how that share compared to CIL referrals for adults and the differences across VR agencies. We divided the VR agencies into three types, based on how they are organized at the state level. A state can either have two VR agencies (a blind VR agency that offers services to people with visual impairments and a general VR agency that offers services to all other people) or one VR agency (a combined agency that offers services to all people). In PY2019, 34 states, territories, and the District of Columbia had a combined VR agency, and 22 states had both a general and a blind VR agency, for a total of 78 VR agencies (we did not have data on the VR agency for American Samoa). We also examined VR agency-level data on the number and share of youth who used comparable services from CILs.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of data at the individual level. We identified and compared the characteristics of and the services used by youth who were and were not referred to VR agencies by CILs. We examined the types of VR services youth use from CILs, regardless of their referral status, and compared the characteristics of youth who did and did not use any services from CILs.

We extended the descriptive analyses with bivariate ordinary least squares regression models and t-tests to detect significant differences between groups of interest on their characteristics at application and use of VR services. Group comparisons included youth who were and were not referred by CILs, non-Hispanic white and other youth, and youth who did or did not use CIL services.

A Supplemental Appendix contains additional tables that support the results presented in this paper, including statistics by VR agency.

Results

How Common Are CIL–VR Collaborations?

At the agency level, the intersection between CIL referrals to VR agencies and VR youth using CIL services provides a high-level view of the relationships—or potential for relationships—between these two entities to support the transition of youth into adulthood. Table 1 summarizes the types of referral and service relationships between VR agencies and CILs, based on the PY2019 patterns detailed in later tables.

More than half the VR agencies received at least one youth referral from a CIL, but several agencies never received any. Of the 77 VR agencies, 42 had at least one youth referral from a CIL (all of which also had adult referrals from a CIL), 12 had at least one adult referral from a CIL but not a youth referral, and 23 had no youth or adult referrals from a CIL.

VR agencies do not commonly record CIL services delivered to youth as comparable services and benefits providers. Only 26 VR agencies had at least one youth recipient who used such services, whereas the majority (n = 51) did not.

Fifteen VR agencies had both youth CIL referrals and youth who used CIL services. The relationships between the VR agency and CILs in these states may therefore be stronger than the 14 VR agencies that had no youth or adult CIL referrals and also had no youth using CIL services. Additionally, the nine VR agencies where youth used CIL services but did not receive any CIL referrals could build on those relationships to encourage referrals from CILs.

What Are the Referral Patterns from CILs to VR Agencies for Youth with Disabilities?

CILs refer very few youth to VR, either nationally or for any single VR agency. Nationally, 570,781 youth had applied for or used VR services in PY2019. Of these, 568,221 had a referral source, of whom CILs referred only 664 (about 0.1%) (Figure 1). Among VR agencies with any youth CIL referrals, the number ranged from less than 10 youth (24 agencies) to 142 youth (Illinois). Almost half (35) of VR agencies had no youth CIL referrals. The absence of youth referrals is particularly notable among blind VR agencies: of those 22 agencies, only three (Missouri, New York, and South Dakota) had any youth CIL referrals. VR agencies in highly populated states (such as California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania) received the most CIL referrals. However, due to their large caseloads, these numbers might not always mean a higher share of youth referred by CILs. For example, the 15 youth CIL referrals for the Alaska VR agency represented 2.2% of its youth referrals, the largest share of any agency. In contrast, the 142 youth CIL referrals in Illinois represented 0.5% of that agency’s youth referrals.

For comparison, we also examined the number of CIL referrals for adults aged 25 or older (Supplemental Appendix Table A.1). In PY2019, VR agencies had 598,588 adults who had applied or used services, of whom 596,326 had a referral source and 1,653 had a CIL as a referral source. Adults had a higher share of CIL referrals (0.3%) than did youth (0.1%). Many VR agencies had similar patterns of CIL referrals for youth and adults. For example, all VR agencies with youth CIL referrals also received adult CIL referrals, and 23 VR agencies had neither youth nor adult CIL referrals. Notably, no agency had zero adult CIL referrals and at least one youth CIL referral. In addition, six of the 19 blind VR agencies that did not have youth CIL referrals did have adult CIL referrals.

What Were the Characteristics of Youth Referred by CILs to VR Agencies, and What Services Did They Use?

VR youth who were and were not referred by CILs had different characteristics at the time of their VR application. Compared with other youth, those referred by CILs were more likely to be older, White, employed at the time they signed their IPEs, reside in a community residential facility or group home, have a secondary school diploma or equivalent, and receive public support (such as Social Security Administration disability benefits) (Table 2). They were also less likely to be Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black, be a student with a disability, reside in a private residence, and rely on family and friends as a source of support. Finally, compared to other youth with VR cases, youth referred by CILs were more likely to have certain barriers to employment, such as being long-term unemployed, low-income, identified as basic skills deficient or low levels of literacy, or currently in foster care or having aged out of the foster care system. The one exception to this pattern is that they were less likely to be English language learners. In sensitivity tests, these results were robust to excluding VR agencies that did not have any youth referred by CILs (results not shown).

As an alternative consideration, we examined referral patterns across subgroups of youth by race and ethnicity (Supplemental Appendix Table A.2). Compared to VR youth who were non-Hispanic White, VR youth from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds were less likely to have been referred by CILs (0.08% and 0.15%, respectively). In addition, among VR youth from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, those who were referred by CILs differed in characteristics from those who were not referred; however, these same differences also existed for White youth, which suggests that the main source of differences in characteristics was between CIL and non-CIL referrals, regardless of race and ethnicity.

We examined 23 VR services in this analysis and found significant differences in the use between youth referred by CILs or by other sources for 13 of them. The most frequent services used by youth, no matter their referral source, were assessment, VR counseling and guidance, and job search assistance, and youth referred by CILs had higher rates of use for the latter two services than did youth referred by other sources (Table 4). In addition, youth referred by CILs were more likely to use other services, such as diagnosis and treatment of impairments and benefits counseling. Aside from job search assistance, referral source was not a defining difference in the use of most career services; the exception was the other employment service category, which more youth referred by CILs used. Among training services, youth referred by CILs also were more likely to use on-the-job training and disability-related skills training; about 2% of youth from other referral sources used these services, whereas 8% to 9% of youth referred by CILs did. Youth referred by CILs were less likely to use college training services than their counterparts. Despite being less likely to be students than those from other referral sources, youth referred by CILs had higher use of four of the five pre-employment transition services, which are typically only available to youth under age 22 (though this age limit can differ across states) who are currently enrolled in secondary or postsecondary education or another recognized educational program. Within the category of other services, we found a single difference between the groups: youth referred from sources other than CILs had higher use of maintenance, which offers monetary support to cover additional costs youth incur while receiving VR services, compared to those referred by CILs.

To What Extent Do VR Youth Use CIL Services, and What Are the Characteristics of Youth Who Do So?

About one-third (n = 26) of VR agencies had at least one youth who used any services from a CIL as a comparable services and benefits provider in PY2019. Their number (n = 851) represented 0.12% of all VR youth, a share that was higher than the 0.06% we observed for adults in that year (data not shown). The general VR agencies in Michigan and Minnesota reported the most youth using CIL services, with 184 youth and 359 youth, respectively, comprising 64% of all such youth nationally (Figure 2). The remaining results thus primarily reflect the experiences of youth from these two agencies (Supplemental Appendix Table A.1).

Among youth who used any services from a CIL, the two most common CIL services were workplace readiness training (25%) and instruction in self-advocacy (20%) (Figure 3). Since both are pre-employment transition services (and therefore typically only available to students with disabilities under age 22), these statistics underscore the roles of some CILs in helping young people with disabilities with career exploration and preparation for adult life. Other commonly used CIL services included benefits counseling (13%) and disability-related skills training (12%), which fall under the more traditional umbrella of CIL services.

The characteristics of youth who used CIL services are consistent with their greater likelihood of using pre-employment transition services (Supplemental Appendix Table A.3). Compared to those who did not use any CIL services, youth who used CIL services were younger (by 4 months on average) and were more likely to be a student with a disability, non-Hispanic White, have not yet have obtained a secondary school diploma or equivalent, have a sensory or communicative impairment (rather than a mental disability), not be employed when they obtained an IPE, receive public support, and have certain barriers to employment, such as long-term unemployment identified as basic skills deficient or low levels of literacy. In sensitivity tests, these results were robust to excluding VR agencies that did not have any VR youth using CIL services (results not shown).

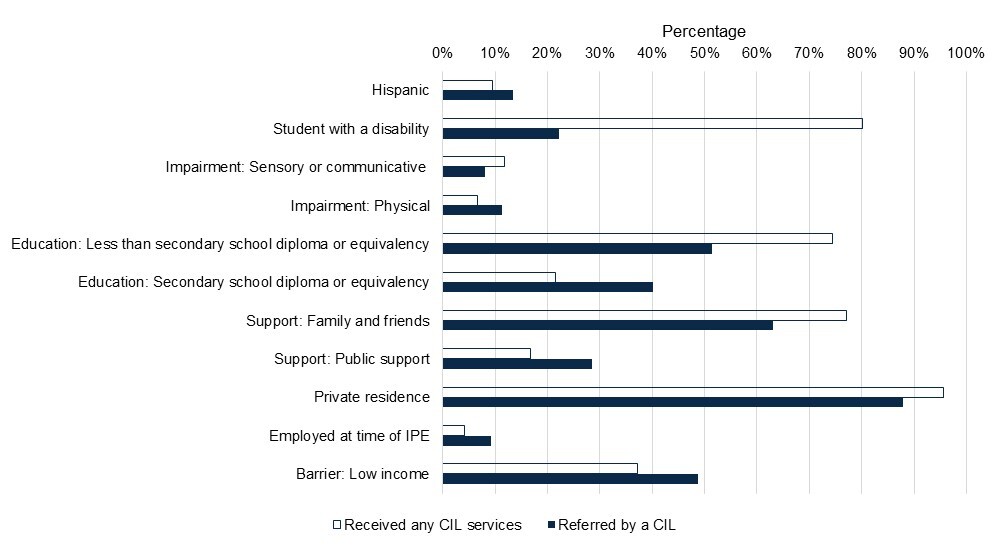

An interesting pattern emerged when we compared the characteristics of youth involved in the two types of CIL–VR interactions. Figure 4 shows a comparison of select characteristics that differed significantly between the two groups of youth. Compared to the 851 youth who used CIL services, the 664 youth referred by CILs were on average older (by about one year) and less likely to be a student with a disability or reside in a private residence. Youth referred by CILs were more likely to be Hispanic, have a physical disability, have at least a secondary school education, receive public support, be employed when they obtained an IPE, and have low income, compared to youth using CIL services. A caveat to these comparisons is that the two groups of youth are not mutually exclusive, as the same young person could both be referred by a CIL to the VR agency and use CIL services.

Discussion

The findings of our study highlight the potential for more collaboration between CILs and VR agencies at the state and local levels. Of the 77 VR agencies examined, 42 had at least one referral of a young person age 14 to 24 from a CIL, and the rest had none. We also found evidence that some VR youth use CIL services, and we expect that our estimates, if anything, underestimate the extent to which youth use CIL services. However, we also found significant variation in these relationships between CILs and VR agencies. On the one hand, some VR agencies had no observed connections with CILs, at least as identified by referrals and comparable services and benefits providers. On the other hand, a handful of agencies receive a non-trivial number of CIL referrals or have many youth using CIL services. Interestingly, the one type of collaboration did not always correspond with the other: 38 agencies had either CIL–VR referrals or youth using CIL services, but not both. Taken together, these findings suggest that more could be done: CILs and VR agencies that have no connections could begin exploring them, while others that have some connections could consider building on them by including more youth, both types of collaborations, and additional services.

Generally, CIL referrals make up a small share of all youth engaged with VR. Only one of the 77 VR agencies examined (Alaska) had enough CIL referrals to comprise at least 1% of the youth it served in PY2019. Several reasons could explain the low rates of referrals. In some states, VR agencies are in order of selection, such that they must limit and prioritize the youth they serve; in these cases, CILs might not bother referring youth or might selectively refer the youth most likely to benefit from employment services because they expect most youth have a low probability of accessing services. As of August 2021, 38 VR agencies operated under an order of selection (RSA, 2021). Lack of follow-through on CIL referrals or other negative experiences might dampen referrals if CILs do not see VR agencies as valuable partners or viable service providers. Alternatively, some CILs might offer similar employment-related services as VR agencies or rely on other providers for these services. If so, they might not perceive a need for VR agencies because they view them as substitutes (or at least not as complementary). Finally, it might be that youth who use CILs have low demand for referrals to VR agencies. For example, many people connected with CILs might not be pursuing employment or in need of employment services because they are already working. Alternatively, they might have been connected to VR through their schools by the time they connect with a CIL.

Compared to referrals, it was even less common for an agency to record youth using services from a CIL; of the 77 VR agencies examined, only 26 had at least one young VR recipient use CIL services as a comparable services and benefits provider in PY2019. Importantly, this is likely to be an underestimate because we cannot observe youth who used services that the VR agency purchased from a CIL, and VR agency staff might not be aware of all the services their clients use. Moreover, a recent survey of CILs identified that almost all received referrals from VR of out-of-school youth from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds (Harrison et al., 2022). Among youth who used any services from a CIL, the two most common CIL services were pre-employment transition services only available to students with disabilities. This pattern not only underscores the roles of some CILs in the youth transition environment but also suggests that CILs may support VR agencies with capacity issues in meeting their WIOA obligations to provide pre-employment transition services to all eligible students.

One notable pattern in our findings is that, compared to general or combined VR agencies, blind VR agencies appear to be particularly unlikely to receive CIL referrals. The reason for this is not known. It might reflect a difference in the composition of youth served by CILs versus VR agencies. Alternatively, youth who are blind might already use VR services before working with a CIL, or it could also be driven by CILs’ perceptions of the goals and needs of blind youth.

What is the correct relationship between CILs and VR agencies? We do not know, and what the data can tell us is limited. CIL and VR services could potentially play complementary and reinforcing roles in supporting youth’s transition to adulthood. CIL services, such as peer counseling and individual and systems advocacy, could help make successful employment a reality for youth, and in turn, stable paid employment can facilitate independent living. However, at the state and local levels, there is potential for confusion of organization and staff roles and duplication or overlap of services. Moreover, youth and families may face overlap among all of the transition-specific providers: the VR agency, CILs, secondary and postsecondary education institutions, and other organizations. These issues point to an increased need for coordination among organizations to ensure efficiency and simplicity from the youth’s and families’ perspectives, while effectively leveraging available resources to maximize benefits for the youth.

Interestingly, the characteristics of youth who are involved in the two types of CIL–VR collaborations differ from each other (though notably, youth who are referred by CILs and those who use CIL services are not mutually exclusive). Unobserved youth-level factors could influence whether youth are referred by a CIL to a VR agency, such as their motivation for employment, and determine whether youth use CIL services, such as condition severity. Alternatively, this difference in characteristics prompts questions about the agency-level processes, such as local relationships or differences between VR counselors, that lead to these collaborations and why different types of youth end up being selected for or involved in the different types of collaborations.

The findings on service use also suggest that VR agencies and CILs might have different comparative advantages for services offered to youth. Among youth who used any VR services from a CIL, the common CIL services used were pre-employment transition services such as workplace readiness training and instruction in self-advocacy, along with benefits counseling and disability-related skills training. VR agencies might rely on CILs for pre-employment transition services due to capacity concerns, and also draw on CILs’ relative strengths in offering disability-specific independent living services. In contrast, youth referred by CILs to VR agencies most commonly used employment services such as VR counseling and guidance and job search assistance, both of which they were more likely to use compared to youth referred from other sources. If these comparative advantages are strong, it further supports the potential for collaborations between CILs and VR agencies in states without such collaborations.

Youth involved in CIL–VR collaborations (either through referrals or service use) are more likely to be non-Hispanic White, compared to youth who are not involved in such collaborations. Conversely, youth who belong to a racial or ethnic minority group are less likely to be involved in CIL–VR collaborations. The current analysis does not allow us to understand this disproportionality. Possibilities include the composition of youth and families who connect with CILs or the general population with disabilities in the few states with many youth who are part of CIL–VR collaborations. However, another possibility could be that the factors that lead to youth being involved in CIL–VR collaborations intersect with their racial or ethnic identity. For example, youth from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to use services despite being eligible (Yin et al., 2021). Because we have a limited understanding of the factors that drive selection for referral, we cannot assess any inequities in the processes that determined youth’s involvement in CIL–VR collaborations.

Limitations

The analysis and findings provide insights about two specific relationships between CILs and VR agencies around youth with disabilities: (a) CIL referrals to VR agencies and (b) CIL services that VR youth use but are not paid for by the agency. Some statistics reflect small sample sizes (such as for individual VR agencies or in calculations for racial and ethnic minority youth referred from CILs), which prevents making broad generalizations. Nonetheless, they represent the entire population of interest: youth who applied for or used VR services in PY2019.

Our findings represent a lower bound of the relationships between CILs and VR agencies as recorded in VR administrative data because of limitations with those data. First, the RSA-911 records have no detailed information on the provider of purchased services, so we cannot identify the extent to which VR agencies purchase services from CILs and we can only examine VR services that CILs provide as comparable services and benefits providers. Many VR agencies likely contract with CILs for purchased services, but we cannot observe them in the available data. Second, even youth’s use of CIL services as comparable services and benefits providers might be underreported because VR staff might not be aware of youth using such services. Third, youth might not disclose that CIL staff recommended VR services when they complete their VR applications or VR staff might be otherwise unaware of the CIL as a referral source, and so the RSA-911 records may underreport youth CIL referrals. Finally, we excluded youth who were enrolled in school and were using pre-employment transition services but had not applied for VR services. We made this choice because VR agencies do not collect information for these youth on key characteristics, such as sex and impairment. Including these youth may have affected the statistics on the share of VR youth referred by CILs or using CIL services.

As mentioned previously, this study is part of a research project funded by NIDILRR to promote the outcomes of youth with disabilities from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds who use CIL services. We originally intended to focus on the intersection of CILs and VR agencies in serving such youth, but the small numbers of youth in our sample prevented a deep dive into the specific experiences of this population with CIL–VR collaborations and how they may differ from youth who are non-Hispanic White. Future research should consider alternative methods such as qualitative interviews or surveys that can overcome the issue of sample sizes to understand their experiences with these interactions, as well as using CIL and VR administrative data within a single state to obtain more detailed data about their collaborations around youth broadly and youth from racial and ethnic minority populations more specifically.

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research

The findings point to opportunities for more connections between CILs and VR agencies. Further, CILs and VR agencies might have comparative advantages in offering different services; thus, each may find a potential efficiency to be gained through closer collaborations. However, the evidence does not tell us about the optimal relationship between CILs and VR agencies, exactly who benefits from them (and how much), or whether youth could use additional supports in their applications or connections between the two organizations.

Administrators from CILs and VR agencies could examine the statistics presented here along with the data to which they have access. Such information would allow them to answer questions about the value of these relationships and their opportunities for collaborations. For CILs, could they refer more of their youth to VR agencies, if those youth have employment goals they want to achieve? For VR agencies, could they better leverage the services that CILs offer youth (along with their families) related to independent living? For both organizations, are some youth more likely—or less likely—to be involved in CIL–VR collaborations, and is this the right balance? Specifically, the detailed service data that VR agencies have could allow them to identify how they currently use CILs in their transition-related work and explore untapped potential. This information can inform them about which CILs they use, for what services, and which types of youth use them and might benefit from them. Answers to these questions might be important to understanding and evaluating issues around service equity.

To support more research on VR agencies’ collaborations with other agencies, RSA might consider adjusting the RSA-911 records so that agencies include the same details on providers of purchased services as they do for comparable services and benefits providers. This change would allow RSA and others to more closely examine how agencies leverage providers for purchased services and explore the provider networks on which agencies rely. In addition, RSA might also consider collecting more data on characteristics of youth who use pre-employment transition services without applying for VR; including such youth in future analyses could increase the generalizability of findings to all users of VR services. However, any revisions that RSA makes to the RSA-911 should consider the burden of those changes on the part of VR agency staff and their data collection systems against the benefits to be gained.

This study is the first to explore the extent to which CILs and VR agencies collaborate on their referrals and service provision to transition-age youth, but much remains unknown about these collaborations. First, future studies could explain why only some CILs and VR agencies collaborate and why only some youth are involved in such collaborations. These studies could inform considerations such as identifying and building optimal contexts for collaborations and effectively targeting efforts to increase collaborations at the youth or agency levels. Second, we found notable differences in the characteristics of youth who are and are not involved in CIL–VR collaborations. For example, youth referred by CILs to VR agencies in PY2019 were more likely to be older, be non-Hispanic White, and have a secondary education diploma. A better understanding of the mechanisms behind the selection of youth for involvement in CIL–VR collaborations could shed light on the potential equity implications of the processes behind these collaborations. Third, while past research underscores the importance of interagency collaboration, we have no rigorous evidence on the outcomes of CIL–VR collaborations specifically. Before recommending a broad and strong push to encourage CIL and VR agency collaboration, more evidence may be needed on how effective collaborations can improve youth’s outcomes and the contexts in which such collaborations are successful in helping youth.

Conclusion

Youth with disabilities and their families face many opportunities and challenges in their transitions from school to young adulthood. CILs and VR agencies offer unique and complementary services many youth could use. In this study, we documented the collaborations between CILs and VR agencies in their work with transition-age youth. Though many CILs and VR agencies do work together, the number of youth connecting to both organizations appears limited. Our findings suggest the potential for increased collaborations, and they also raise questions as to why VR agencies receive so few referrals from CILs and CILs offer so few services to VR youth. Youth and families, along with staff from CILs, VR agencies, and other transition providers, could benefit from stronger collaborations between CILs and VR agencies around services that promote transitions and improve equitable access to services.

Funding Note

Funding for this manuscript was provided by the Disability and Rehabilitation Research Project on Minority Youth and Centers for Independent Living at Hunter College, City University of New York, which is funded as a cooperative agreement, jointly by the Office of Independent Living Programs and the National Institute for Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, both in the Administration for Community Living, at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under grant number 90DPGE0013. The contents do not necessarily represent the policy of DHHS and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

.png)

.png)